The Polymath Influencer Who Invented the Scientist

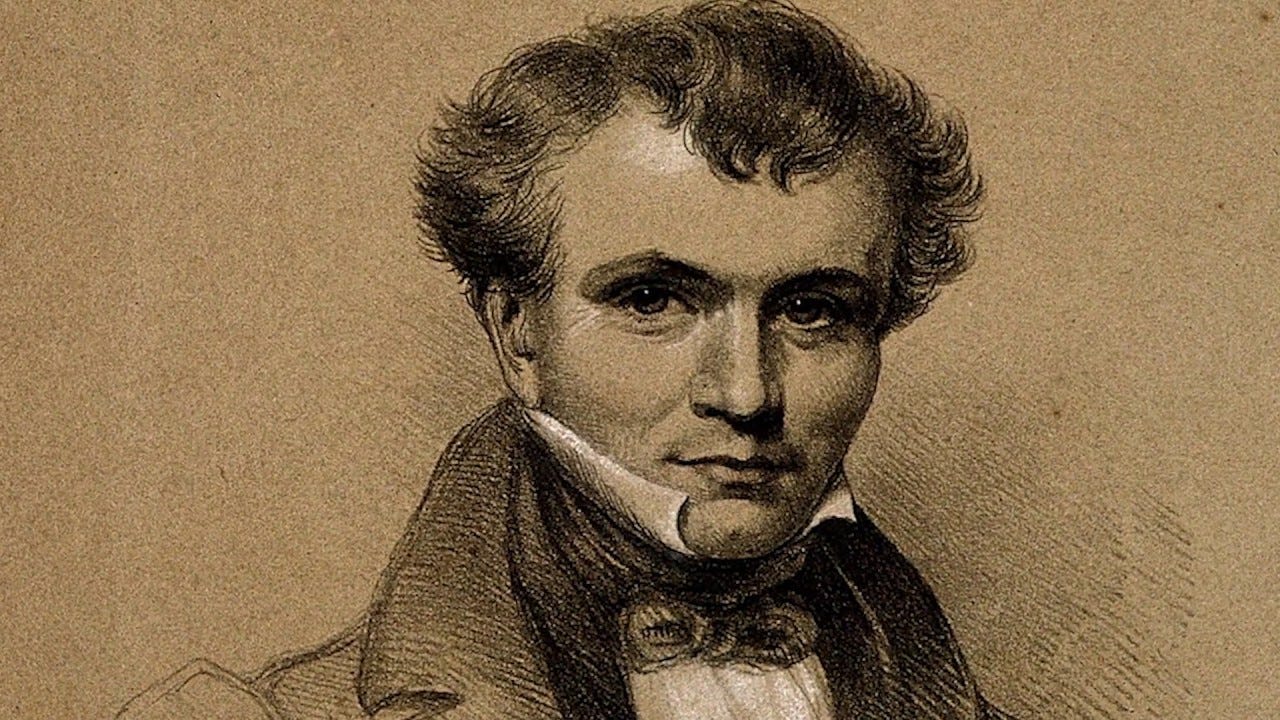

William Whewell on knowing the Mind of God through the truth of science.

Image: loff.it

Science as it exists today owes much to the nineteenth-century English polymath William Whewell. A Master of Trinity College, Cambridge, and “meta-scientist” who conducted and published research in mechanics, geology, physics, paleontology, mineralogy, astronomy, chemistry, oceanography, and botany, Whewell was likewise an accomplished mathematician, poet, philosopher, political economist, historian, ethicist, and theologian.

As the first systematic writer on the history and philosophy of science, he was also the first to articulate—and name—the hypothetico-deductive method, the classical scientific method of Sir Francis Bacon. Whewell was likewise “the person most responsible in the English-speaking world for crafting the social role of the scientist.”1 Coining the term “scientist” to describe men—such as Sir Isaac Newton, Robert Boyle, and James Clerk Maxwell—who methodologically investigate nature by means of experiments, Whewell articulated a philosophical vision of science that was a century ahead of its time.

Understanding the central role of falsification, coherence, consilience, cultural values, and even metaphysical presuppositions as necessary foundations of true science, Whewell anticipated many of the conclusions of 20th-century philosophers of science such as Sir Karl Popper, Michael Polyani, and Thomas Kuhn. For Whewell, though, science both begins and ends with God—because “as science progresses, it reveals necessarily truths and thereby grants a glimpse of the Mind of God.”2

The Greatest Influencer of the Second Scientific Revolution

Due to the great advances in our understanding of the natural world that took place in England and Europe during the 19th century, and owing to the key developments during this time that would forever shape the future of the natural sciences, this age has often been called the “Second Scientific Revolution.” During this Second Scientific Revolution William Whewell stands out as a scientist who had an impact and influence beyond all others of his age.

Whewell personally influenced practically every field of science during this period in a significant way. He was an active and influential member of over a dozen scientific societies, a moving force in the founding and running of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, President of the Geological Society, an influential Master of Trinity College, and a pioneering Vice Chancellor of Cambridge University during his two terms of office.

He was repeatedly sought out as a scientific advisor by luminaries such as physicist James Clerk Maxwell, physicist Michael Faraday, biologist Charles Darwin, astronomer William Herschel, mathematician and physicist Robert Murphy, mathematician George Peacock, “father of the computer” Charles Babbage, and geologists Adam Sedgwick and Charles Lyell (who initiated and sustained scientific correspondence with Whewell through lengthy letters for over a 30 year period).3

In his extensive publications, Whewell spoke with authority and originality on almost every topic on the early Victorian intellectual agenda. His works included “original scientific investigations, university textbooks on physics and mathematics, books on ethics and law, university education, natural theology, church architecture, scientific nomenclature, political economy, and the history and philosophy of science—to name but the most important.”4

Whewell’s History of the Inductive Sciences (1837) and Philosophy of the Inductive Sciences (1840) became “the standard history of science texts for decades.”5 Beyond his scientific studies, he published poetry, translated Greek and German classics, edited the works of Hugo Grotius and Isaac Barrow, and participated energetically in several major debates, such as those concerning the plurality of worlds and Darwin’s theory of evolution.

As the “most profound and prolific writer of his generation,” Whewell was “not merely a polymath” but a Renaissance Man on a mission to encompass the entire world of early Victorian learning within his literary and scientific, historical and philosophical, moral and theological works, and to synthesize it and render it a unified intellectual whole for the sake of future generations. “One of the most eminent and influential individuals of the era,” Whewell’s “accomplishments were considered legendary” even to his contemporaries.6

A Scientific Wordsmith and Cultural Communicator

Image: britannica.com

As the most sought after scientist and influencer of science in his age, Whewell coined and popularized many of the scientific terms that would be passed down as vocabular canon to future generations of scientists. For instance, Whewell popularized the term “science” to describe an enterprise that was previously referred to as “natural philosophy” or “experimental philosophy.” After the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge criticized the leading members of the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BAAS) in 1833 for calling themselves “philosophers,” Whewell proposed the neologism “scientist”, which he devised by analogy with “artist”.7

Whewell’s new term “scientist” won out over the other terms being considered by members of the BAAS, such as the German term “Naturforscher” which translates as “nature-poker”. At the request of Michael Faraday, who was seeking a way to better communicate his discoveries to the public, Whewell coined the terms “anode”, “cathode” and “ion”. In response to Charles Lyell’s request to coin new names to describe the Tertiary Geological Period in his 1830 magnum opus Principles of Geology, Whewell suggested the names “Pliocene,” “Miocene,” and “Eocene” for three new geological epochs.

Other terms coined by Whewell that persist in common scientific usage to this day include “physicist,” “consilience,” “catastrophism,” “uniformitarianism,” “astigmatism,” “carnivore,” “insectivore,” “nebular hypothesis,” “osmosis,” “conductivity,” “heuristic,” and “linguistics.”

Defining the Nature of the Scientific Enterprise

As Whewell defined many of the terms that would be passed on to future generations of scientists, he also sought to systematically demarcate the nature of the scientific enterprise itself. Coining the phrase “hypothetico-deductive method” to describe the Classical model of science as understood by Sir Francis Bacon. Whewell went on to argue that “no significant scientific discovery was ever made solely by following Bacon's method of pure induction.”

Arguing from his knowledge of both the history of science and the practice of science in his own day, Whewell was the first to offer a comprehensive and critical alternative to Bacon. Whewell pointed out that Bacon’s “hypothetico-deductive method” overemphasized the purely empirical or observation-based approach to knowledge acquisition and neglected the crucial role of theoretical ideas and concepts in scientific discovery. For Whewell, empirical inquiry involves both a subjective and an objective component. Anticipating the contemporary Kuhnian notion of theory-ladenness—that scientific observations are not purely objective but are influenced by the theoretical framework (or “paradigm”) a scientist already holds—Whewell describes scientific facts as “idea-laden.”

Whewell also suggested that “bold imagination” is required for science to proceed and that scientific discovery is not just a matter of following the facts and employing the proper method. Whewell pointed out that scientists like Johannes Kepler and Newton make bold, imaginative conjectures which are then—a posteriori—either supported by the facts or refuted by the facts (and rejected).

If a theory is supported by the facts, it must pass the further tests of “prediction, consilience, and coherence” before it may be considered scientific truth. The first test of prediction, says Whewell, entails that scientific “hypotheses ought to foretell phenomena which have not yet been observed” and be able “to predict unknown facts found afterward to be true.”8

Second, consilience requires that a scientific theory should “explain and determine cases of a kind different from those which were contemplated in the formation” of those hypotheses. In other words, consilience is the linking together of facts and principles from different disciplines—such as Maxwell’s explanation of light, magnetism, and electricity as being essentially the same physical phenomenon as viewed from different perspectives.

Third, explains Whewell, a hypothesis must “become more coherent” over time. Coherence occurs when a theory can be extended to connect and make sense of new types of phenomena without ad hoc modification of the original hypothesis.

How Scientific Truth Leads to the Mind of God

Image: youtube.com

According to Whewell, scientific progress is made when we discover “Fundamental Ideas”—classificatory concepts that turn out, after rigorous empirical testing, to have been necessary all along. For him, such fundamental ideas can be understood as “forming the nodes in a theoretical network that…constitute the creation plan God used when creating the universe.”9 Furthermore, says Whewell, these fundamental ideas, or necessary truths, give us a “glimpse of the complete and final truth contained in the Mind of God.”

The final goal of science, then, is to discover that “the world is as it is, necessarily, because that is the way it has been created by a good God—it is the way it is because it is held immanently by this good God.”10 Yet, fundamental truth, however necessary, does not come easily without great effort. Science — and God — make you work for it, but for Whewell, God and Science are ultimately just “different sides of the same coin.”

For Whewell, humans—through their scientific endeavors—have a central “role to play in the cosmic unfurling of God’s creation.” Beyond our moral tasks, says Whewell, we have the intellectual duty of the “study of the natural world,” which ultimately “leads to contemplation of its divine Creator, His power, wisdom, and benevolence.” According to Whewell, “the discovery of laws of nature did not make it unnecessary to think of God, for they were no power or agency in themselves but only the rules by which the supreme Agent operated.” Whewell was confident that “God made this magnificent world, and he expects us to work at discovering its guiding laws. As we do this, and inasmuch as we do this, we show our love of and respect for the Lord.”11

Attacked by Atheists and Maligned By Myth Makers

During his lifetime, Whewell waged rhetorical war against the Positivist understanding of science and society, as articulated by Auguste Comte and his followers. According to Positivism, the only true knowledge is that which can be scientifically verified or established through logical or mathematical proof. The Positivists faulted faith as foolish, mocked metaphysics as merely mythological, denounced theistic belief in God as irrational nonsense, and dismissed Scripture as pointless poetry.

Beginning in the 1830s, Whewell feared that the ascendancy of the Positivist paradigm in Britain and Europe would “[put in] serious and extensive jeopardy the interests of the civilisation of England and of the world” and “bring to an end” not only true science, but “the passing on of Ideas that were Divine, permanent, and fundamental to the human mind.” The purpose of Whewell’s philosophy of knowledge and his ideal of liberal education was to “pass on the torch” to succeeding generations and so prevent the Positivist—and Marxist—movements from coming to power, for he believed, correctly, that if they did so, it would mean the end of civilization and society as he knew it.12

The Positivists struck back in the 1870s, a decade after Whewell died. A group of ambitious, secularist scientists and Positivism popularizers commenced an all-out attack on Whewell’s philosophy of science. “Whewell's ideas were declared defeatist since he made science dependent upon ingenuity and luck.”13 They denounced his view of science as undermining objectivity because it relied too much on the subjective component of human experience.

These Positivists especially chided Whewell’s integration of theology and science and his contention that true science would ultimately lead one to the Mind of God. As Scientistic Positivists increasingly came into power, “the act of consigning the works of Whewell to oblivion began at once.”14 The “new generation of professional men of science, such as Thomas Henry Huxley and John Tyndall, proclaimed the separation, even the antagonism, of science and religion.”15 They were “devoted to spreading the gospel of naturalism” at home in England and in America through “lay sermons,” popular books, writing and speaking tours, and new periodicals—such as Nature, Scientific American, and Popular Science.

Positivist activists sought to influence scientifically literate individuals, “especially those who exercised control over universities and the scientific thinking and research that occurred there.”16 Anti-religious Positivism-promoters “slowly created a new vocabulary for discussing natural events and objects, and challenged implicit (yet vital) religion-friendly assumptions about the relationships that could occur in the natural world.”17

This new breed of scientist also “reassigned intellectual property rights, radically expanding the domain in which positivist scientists could legitimately speak, and relentlessly contracting the domain in which others could legitimately speak.”18 In order to establish “an autonomous space in which they could speak about any subject and draw any conclusion, without challenges based on religious values and assumptions,” the new class of professional Positivist scientists needed openly to “abrogate all treaties with the religion-friendly view.”

In the end, “such discursive strategies allowed positivist activists to proffer themselves not only as the only relevant scientific ‘experts,’ but also as the only capable judges of what qualified as ‘true religion.’” The consequence was that Whewell, “though famous and influential in both philosophical and scientific circles…was maligned to the degree that he had to be rediscovered” a hundred years later.19

The Death of Positivism and the Resurrection of Whewell

In the late 1960s, about a hundred years after the meteoric rise of Positivism, its star fell to earth, and it was pronounced “dead, or as dead as a philosophical movement ever becomes.”20 The beginning of the end of Positivism arrived in 1931 when Kurt Gödel, the greatest mathematician and logician of the 20th century, proved that no finite system—of logic or anything else—can be used to derive all of mathematics. Gödel's incompleteness theorems undermined the foundations of positivism by demonstrating fundamental limitations to formal systems and the logical inadequacy of the verifiability principle that Positivism relied on.

Another critical blow to Positivism came in 1946 when chemist and philosopher of science Michael Polanyi articulated the vital role that personal commitments and tacit knowledge play within the practice of science. Polanyi rediscovered Whewell’s conception of science and spoke of the “wonderful surprise of finding [his own] basic assumptions” in Whewell’s work.21 A decade later, philosopher of science Karl Popper thoroughly rejected positivism’s thesis that it is possible to verify or prove a given scientific theory. Popper argued that it is not logically possible for a scientific theory to ever be proven, but rather that a theory can only be falsified. Popper’s The Logic of Scientific Discovery (1959) was greatly indebted to the work of Whewell, and he followed Whewell in placing hypothesis testing and falsification at the center of scientific discovery.

In 1962, Thomas Kuhn's The Structure of Scientific Revolutions popularized much of what Polanyi had established. Kuhn further developed a concept that Whewell had introduced over a century before—the idea of scientific revolutions. By the close of the 20th century, Whewell’s conception of science had been brought back to life and firmly reestablished under the names of those who—knowingly or not—followed closely in his footsteps.

Steve Fuller, “Introduction” in Defining Science: William Whewell, Natural Knowledge and Public Debate in Early Victorian Britain (Cambridge University press, 2023) by Richard Yeo. Social Epistemology Review and Reply Collective 12 (8): 12–20.

Ragnar van der Merwe, “A Pragmatist Reboot of William Whewell's Theory of Scientific Progress,” Contemporary Pragmatism 20 (3): (2023), 218-245.

Menachem Fisch, William Whewell, Philosopher of Science (Oxford University Press, 1991), 6.

Fisch, William Whewell, Philosopher of Science, 1.

James C. Ungureanu, “Science, Religion, and Nineteenth-Century Protestantism,” Modern Reformation (September 1, 2022).

Fisch, Whewell, Philosopher of Science.

Sydney Ross, Nineteenth-Century Attitudes: Men of Science (Chemists and Chemistry) (Springer: 1991).

William Whewell, Novum Organon Renovatum, (John W. Parker, 1858), 86.

Van der Merwe, “A Pragmatist Reboot of William Whewell's Theory.”

Michael Ruse, “William Whewell: Omniscientist,” in William Whewell: A Composite Portrait Edited by Menachem Fisch and Simon Schaffer (Oxford University Press, 1991), 89.

Michael Ruse, “William Whewell: Omniscientist” in William Whewell: A Composite Portrait, 89.

Perry Williams, “Passing on the Torch,” in in William Whewell: A Composite Portrait Edited by Menachem Fisch and Simon Schaffer (Oxford University Press, 1991), 146-147.

John Wettersten, “Whewell's Problematic Heritage” in William Whewell: A Composite Portrait Edited by Menachem Fisch and Simon Schaffer (Oxford University Press, 1991), 345.

Wettersten, “Whewell's Problematic Heritage” in William Whewell: Composite Portrait, 345.

Williams, “Passing on the Torch,” in William Whewell: Composite Portrait, 147.

Eva Marie Garroutte, “The Positivist Attack on Baconian Science and Religious Knowledge in the 1870s,” in The Secular Revolution: Power, Interests, and Conflict in the Secularization of American Public Life, Christian Smith, ed (University of California Press, 2003).

Garroutte, “The Positivist Attack,” 202.

Garroutte, “The Positivist Attack,” 203.

Wettersten, “Whewell’s Problematic Heritage” in William Whewell: Composite Portrait, 148.

John Passmore “Logical Positivism”, The Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Volume 5), P. Edwards (ed.), (Macmillan, 1967), 52–57.

Lady Drusilla Scott, Everyman Revived: The Common Sense of Michael Polanyi (Eerdmans, 1995), 35.

Wonderful post. I knew of Whewell as the one who coined the term "scientist" but I hadn't realized he had coined so many others (from "linguistics" and "carnivore" to "the hypothetico-deductive method"). Or that he had subjected Positivism to a well-deserved attack.