The Mysterious “X-Club” That Boxed Spirituality Out of Science

How Thomas Huxley perpetrated the greatest conspiracy of the modern age.

Image: infoogm.blogspot.com

Thomas Henry Huxley and the War That Wasn’t

Everybody knows about the age-old war between science and religion: how religion fought tooth and nail to suppress the truth of science; how truth-seeking scientists were persecuted, tortured, or even executed by ignorant, dogmatic religious authorities; and how, for centuries, the light of science struggled to break free from the dark stranglehold of faith, finally emerging victorious as a beacon of objectivity in the modern age.

As atheist defender of science David Mills explains in his bestselling book Atheist Universe, religion “fought bitterly throughout its history—and is still fighting today—to impede scientific progress. Galileo, remember, was nearly put to death by the Church for constructing his telescope and discovering the moons of Jupiter. For centuries, moreover, the Church forbade the dissection of a human cadaver…Historically, the Church fought venomously against each new scientific advance…Those who proposed scientific explanations were often tortured to death by religious authorities.” 1

While certainly entertaining, this captivating story of the scientific war for independence—is essentially fiction.2 It is an ideologue’s tale that was concocted by a number of 19th-century gentlemen (and ladies) in an attempt to secularize science, to free scientific research from religious ethics, and to align science with numerous political agendas and values—such as racism and eugenics—that had long been resisted by people of faith.3

The Mysterious “X-Club”

Image: ebay.com

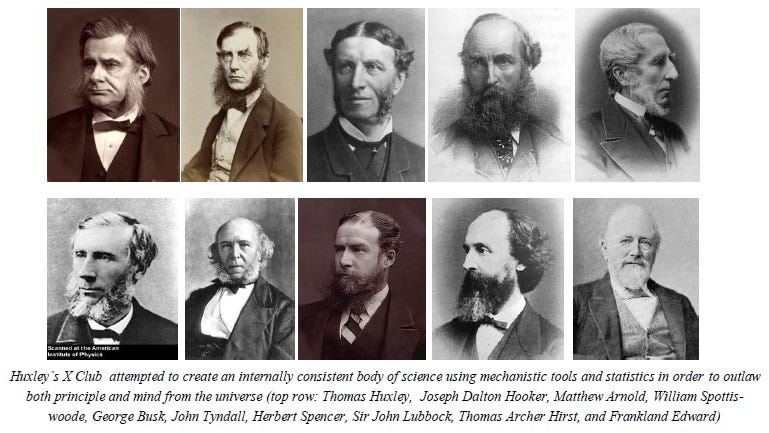

If you have ever heard that people in the Middle Ages thought the earth was flat, that human dissection was outlawed by the Church, that Copernicus was persecuted by priests, or that dogmatic religion has long resisted the truth of science, then you bear witness to the success of a global conspiracy that was spearheaded by a Victorian gentleman’s club so secretive that it never revealed its true name.

Established in the 1860s by the original agnostic, Thomas Henry Huxley, the X-Club, as it was referred to in writing by its members, explicitly “sought with an evangelical fervor…to rid the discipline [of the natural sciences] of women, amateurs, and parsons, and to place a secular science into the center of cultural life in Victorian England.”4 The X-Club ambitiously labored to remove God from science and they rejected “the time-honored belief” of scientists from previous generations “that the scientist’s occupation [was to] discover the glory of God in nature.” 5

The group met almost monthly for a thirty-year period and sought to establish a secular network that would serve as an alternative to the religiously dominated scientific hierarchy. Members were politically active, successfully contriving to alter the election rules of the scientific Royal Society to have their allies elected, and in time they even extended their influence to the position of the presidency. Ruthlessly ambitious, bound by tight personal ties and devotion to a seemingly impossible mission, and working relentlessly to achieve their goals, the agnostic scientific naturalists of the X-Club essentially “engaged in a conspiracy to take over science.”6

Developing a whole new kind of science education, the members of the X-Club produced course syllabi and textbooks, spearheaded exam standardization, ran schools for workingmen, and created schoolboards that would supervise the details of their new vision of science without religion. The X-Club members used all their influence to promote themselves and their allies into key scientific posts.

To extend their influence to an even broader audience, they launched a key journal (one that would have a magazine format, Saturday Review style, but which would be dedicated to science) which Huxley—along with likeminded physicist J. Norman Lockyer—encouraged Alexander Macmillan to publish. This new journal was called by the “glorious title, Nature.” As Huxley proclaimed in the first issue: “Nature! We are surrounded and embraced by her: powerless to separate ourselves from her, and powerless to penetrate beyond her. Without asking, or warning, she snatches us up into her circling dance, and whirls us on until we are tired, and drop from her arms.”7 Nature is “more than Cosmos, more than Universe,” and lies at the “heart of both mind and matter.”

Inventing a War That Never Was

Image: Thomas Henry Huxley, zsl.org

Huxley, the founder and leader of the X-Club, sought to debate his religious enemies on every occasion. A rhetorical master who forced his enemies to entangle themselves in contradictions, Huxley “was evasive and manipulative” and “redefined terms in order to bamboozle opponents.” For him, “words were weapons, chosen for ‘controversial efficiency.’” 8

In his engagement with religion, destruction and combat were Huxley’s typical metaphors, and he redefined the terms “science” and “religion” so that they must be opposed in principle. Proclaiming his “untiring opposition to that ecclesiastical spirit,” Huxley declared that religion “in England, as everywhere else…is the deadly enemy of science.” 9Using a combative biological image in a letter to a coconspirator Huxley asks: “Do you see any chance of educating the white corpuscles of the human race to destroy the theological bacteria which are bred in parsons?” 10

As part of his rhetorical strategy, Huxley enlisted Darwin’s scientific theory to the cause of atheism (even though Darwin himself never accepted this label and originally offered his theory of common ancestry as a way to prove the Bible the right). Having redefined evolution through natural selection as inherently atheistic Huxley had no patience for prominent religious scientists who embraced evolution, such as Harvard Biologist and Evangelical Christian Asa Gray, or Roman Catholic biologist Saint George Mivart.

Mivart, who professed evolution as God’s way of creating life and insisted that Darwinism was perfectly compatible with the Bible’s teaching in Genesis, infuriated Huxley, and he insisted to Mivart and Gray that they must choose whether they wanted to be “a true son of the Church” or “a loyal soldier of science.” 11Huxley’s rhetorical point was that in the “war between science and religion” one cannot fight for both sides.

Huxley reworked history to envision secular science as the victor over oppressive religion. Huxley described how “at the dawn of modern physical science, the cosmogony of the semi-barbarous Hebrew was the incubus of the philosopher and the opprobrium of the orthodox.” He bemoaned how “patient and earnest seekers after truth, from the days of Galileo until now…have been embittered and their good name blasted by the mistaken zeal of Bibliolaters.”

At the hands of those wielding the blunt weapons of Scripture, lamented Huxley, countless scientists have been persecuted and have suffered, but now, thanks to Huxley’s and the X-club’s efforts, “their cause has been amply avenged. Extinguished theologians lie about the cradle of every science as the strangled snakes beside that of Hercules; and history records that whenever science and orthodoxy have been fairly opposed, the latter has been forced to retire from the lists, bleeding and crushed, if not annihilated; scotched, if not slain.”12

The Greatest Preacher of the Age

Huxley envisioned his new “liberated science” as a new gospel that would be spread by the X-Club as “a new set of social Jesuits.” This new gospel would satisfy “Mankind’s emotional needs,” which could “not be satisfied by empty ritual, but by the real awe of Nature’s deep mystery.” 13 To this end, Huxley traveled across England giving “lay sermons,” where the poor were admitted for free, and others fought for tickets. These sermons exalted the “wonders of science” and instilled a new “reverence” in those who did not attend religious worship.

One of Huxley’s lay sermons, in January 1866 at St Martin’s Hall in Covent Garden, was “packed to suffocation” with “every part of the great Hall crowded — every foot of standing room was occupied.”14 As he entered, amidst great fanfare, Joseph Haydn’s Creation oratorio pumped out of the organ. “Science was tearing through the ‘fine-spun ecclesiastical cobwebs’ to behold a new cosmos, in which our Earth is merely an ‘eccentric speck’—a world of evolution ‘and unchanging causation’.” Huxley invited his listeners to entertain “new ways of thinking” that “demanded a new rationale for belief” with science’s truths at the center. The “old authority of religion,” preached Huxley, needed to be “sacrificed on nature’s ‘altar of the Unknown.’” 15

On another occasion, during a lay sermon at the Working Men’s College in Red Lion Square, Huxley denounced “this idolatrous age” which “listens to the voice of the living God thundering from the Sinai of science, and straightaway forgets all that it has heard, to grovel in its own superstitions; to worship the golden calf of religious tradition…to sacrifice its children to its theological Baal.” 16 Huxley’s X-Club friends cheered whenever he managed to “frighten the parsons,” and other devotees sitting in the audience, such as Karl Marx’s daughter Jenny, exulted in the “genuinely progressive” sermons of Huxley—given at a time “when the flock are supposed to be grazing in the house of the Lord.”

Performing rhetorical jujitsu against religion, Huxley established Science as “the bastion of virtue,” while “blind religious faith” was denounced as “immoral superstition” and “the one unpardonable sin.” Demonstrating the “magnificent views of the broad and fertile kingdom of Natural Knowledge,” Huxley argued that Science could become a substitute for religion. “I will make people see what grandeur there is…in Biological Science”, he declared; “that Science and her ways are great facts for them — that physical virtue [i.e. sexual self-control] is the base of all others, and that they are to be clean and temperate and all the rest — not because fellows in black and white ties tell them so, but because there are plain and patent laws which they must obey ‘under penalties.’”17

“Pope Huxley”, as the Spectator magazine called him, converted thousands of people—including many parsons and pastors—to what he called “the Church Scientific.” One Anglican priest followed Huxley’s entire lecture tour and committed to memory his lecture “On the Physical Basis of Life,” as if it were a catechism. Another vicar who had lost his faith left the Church and wrote Huxley desiring to be his disciple, to serve science, and to work under him “as secretary or manager of some sort.” 18 Huxley set up Science as a new religion of which only highly qualified professional secular skeptical scientists could become the new priests.

The X-Women Who Went to War for Science

Image: Matilda Gage, tpt.org

The banner of Huxley’s war against religion in the name of science was also taken up by many leading women of the age. The famous feminist Elizabeth Cady Stanton praised the writings of one of the American auxiliary members of Huxley’s X-Club, Andrew Dickson White. Stanton declares that “Hon. Andrew D. White...shows us in his great work, A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology, that the Bible, with its fables, allegories, and endless contradictions, has been the great block in the way of civilization.

All through the centuries scholars and scientists have been imprisoned, tortured, and burned alive for some discovery which seemed to conflict with a petty text of Scripture.”19 To aid the X-Club’s cause on the American front, Stanton, along with Susan B. Anthony, and Mathilda Gage, produced The Women’s Bible to offer an alternative to the traditional “unscientific religions” of Judaism and Christianity.

Other Victorian ladies, young and old, were flirting dangerously with Huxley’s gospel of a new religion of science. Eliza Lynn Linton—the first female salaried journalist in Britain and the author of over 20 novels—was “intoxicated by Huxley’s talks” in “His Court of Paradise,” the Royal Institution. George Henry Lewes reported to Huxley: “My mother (aged 75) is delighted with your sermon” and Lewes ran Huxley’s sermon in his magazine Fortnightly Review, declaring that he “foresees a change in Religion coming.”20

Huxley often dined at Lewes’ house, the Priory, where Lewes lived in an open relationship of “free love” with Victorian novelist Mary Ann Evans—aka George Eliot. Evans was so impressed with Huxley’s message, that she helped rescue Huxley “from poverty and obscurity” and used her influence with her publisher John Chapman to have Huxley made the Westminster Review’s scientific reviewer—with a handsome salary to boot. Huxley in turn helped his patroness Evans with more intellectual resources to deepen her break with religious faith and—along with future X-Club member John Tyndall—developed the science section of Chapman's periodical.

Chapman and his circle of secular progressive authors, including Evans, social theorist Harriet Martineau, and future X-Club members Huxley, Tyndall, and Hebert Spencer (a social theorist and philosopher who created “social Darwinism” and coined the phrase “survival of the fittest”) worked together to articulate their commitment to a naturalistic version of evolution in the interest in challenging religion—and they did so many years before the 1859 publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species.

The Sunset of Religious Faith and the Rise of the Modern Scientific Age

Huxley pronounced that the “future of our civilization…depends on the result of the contest between Science and Religion which is now afoot.” Religion “must, as a matter of life and death, resist, the progress of science and modern civilization,” and “Theology and Parsondom are in my mind the natural and irreconcilable enemies of Science.” 21 While “Few will see it,” prophesied Huxley “I believe we are on the Eve of a new Reformation, and if I have a wish to live thirty years, it is that I may see the foot of Science on the necks of her Enemies.” 22

By the time of his death in 1895, Huxley’s dream to reshape science and banish religion had been essentially accomplished. In the end, the X-club’s vision of science would emerge victorious and they would usher in a new age of intellectual freedom unshackled by ethics, sexual liberty without restraint, social and racial hygiene, valueless economic policies, modernized warfare, and technological supremacy.

As Huxley and his coconspirators rewrote history and twisted truth to win the day for science, the modern way of viewing the world emerged—“a planet with no God, which an impersonal nature had designed for the superior branches of the human race” who would “while polluting Earth with heavy industry, bring to it incalculable benefits such as mechanized warfare and chemical and nuclear weapons.” 23 Huxley and his X-Club had driven God out of the realm of natural sciences, and the world would never again be the same.

Join our first-ever discussion group! 👇

David Mills, Atheist Universe (Ulysses Press, 2006), 48-49, 85.

Galileo was in actuality honored by the Pope and the Jesuits for discovering the moons of Jupiter. Galileo’s discovery of mountains on the moon, the moons of Jupiter, and the phases of Venus in 1610 did not lead either to his persecution or to any great theological upheaval in the Church. Cardinal Bellarmine asked the Jesuit astronomers at Rome whether they could confirm Galileo’s observations. When they finally obtained a telescope powerful enough to permit confirmation, the Jesuits replied that they indeed saw what Galileo had described, and they went on to make several new discoveries of their own. When Galileo visited Rome in 1611, “he received a hero’s welcome and the Jesuits lauded him openly for his wonderful discoveries.” The Jesuit astronomers in Rome gave a feast in Galileo’s honor and Clavius, the senior member of the Collegio Romano and one of the most respected mathematicians in Europe wrote that “Galileo’s discoveries required a rethinking of the structure of the heavens.” Galileo was elected to the exclusive scientific society the Accademia dei Lincei, support for him spread, and he was soon an acclaimed celebrity. James Hannam, God’s Philosophers: How the Medieval World Laid the Foundations of Modern Science (Washington, D.C.: Regnery Publishing, 2011), 319. Lawrence Principe, The Scientific Revolution: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 61.

For details see Joshua Moritz, The Role of Theology in the History and Philosophy of Science (Brill, 2017)

Peter Harrison, “‘Science’ and ‘Religion’: Constructing the Boundaries,” in Science and Religion: New Historical Perspectives, ed. Thomas Dixon, Geoffrey Cantor, and Stephen Pumfrey (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 27.

Frank M. Turner, Between Science and Religion: The Reaction to Scientific Naturalism in late Victorian England (Yale University Press, 1974).

Matthew Stanley, Huxley's Church and Maxwell's Demon: From Theistic Science to Naturalistic Science (University of Chicago Press, 2014).

Adrian Desmond, Huxley: From Devil's Disciple To Evolution's High Priest (Basic Books, 1997) 372.

Ruth Barton, The X Club: Power and Authority in Victorian Science (University of Chicago Press, 2018) 34.

Ruth Barton, “’An Influential Set of Chaps’: The X-Club and Royal Society Politics 1864–85,” British Journal for the History of Science 23, no. 1 (March 1990): 53–81.

Thomas Henry Huxley, Life and Letters of Thomas Henry Huxley — Volume 3, Leonard Huxley (Macmillan and Company, Limited, 1913).

James R. Moore, The Post-Darwinian Controversies: A Study of the Protestant Struggle to Come to Terms with Darwin in Great Britain and America, 1870-1900, (Cambridge University Press, 1981) 64.

Thomas Henry Huxley, Aphorisms and Reflections: From the Works of T. H. Huxley, by Henrietta Anne Huxley (London: Watts and Co., 1911).

Huxley quoted in Desmond, Huxley: From Devil's Disciple To Evolution's High Priest.

Desmond, Huxley: From Devil's Disciple To Evolution's High Priest, 344.

Huxley quoted in Desmond, Huxley: From Devil's Disciple To Evolution's High Priest, 345.

Huxley quoted in Desmond, Huxley: From Devil's Disciple To Evolution's High Priest, 209.

Thomas Henry Huxley, Autobiography and Selected Essays (1909), vii.

Desmond, Huxley: From Devil's Disciple To Evolution's High Priest, 434

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, The Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, (Rutgers University Press, 2013).

Huxley quoted in Desmond, Huxley: From Devil's Disciple To Evolution's High Priest, 345-346.

Huxley quoted in Darwinism as Religion: What Literature Tells Us about Evolution, Michael Ruse (Oxford University Press, 2017).

Huxley quoted in The X Club: Power and Authority in Victorian Science, by Ruth Barton (University of Chicago Press, 2018), 424.

A.N. Wilson, “The mad, bad and dangerous theories of Thomas Henry Huxley” The Spectator (08 October 2022).

This has inspired me to want to write about the maniacal fascination with astrophysics that I think is an outgrowth of this mentality, but in the meantime, have a couple of articles I enjoy!

https://sheseeksnonfiction.blog/2021/08/15/carl-sagan-was-wrong/

https://telescoper.blog/2018/06/19/why-the-universe-is-overrated/

OMG! I have always argued that science and religion need not be at war with one another. Is Aldous Huxley a descendant of Thomas H? Seems Aldous had to find something bigger and greater than a simplistic materialistic world with no spiritual value.