Robert Boyle and the Chemistry of Creation

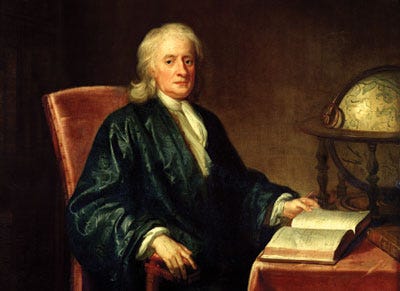

The Father of Experimental Science.

Image: timetoast.com

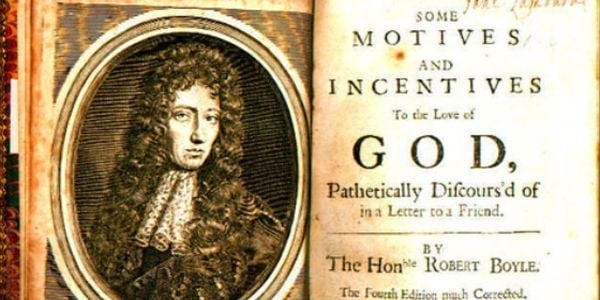

The father of modern experimental chemistry and pioneer of the scientific method, Robert Boyle was a genius beyond reckoning who ranks among Newton, Maxwell, and Einstein as one of the world's greatest scientists. A polymath whose expertise ranged from ancient languages to animal husbandry and from respiratory physiology to medicine and physics, Boyle was also an exceedingly generous philanthropist who cared for the poor in countless ways and tirelessly endeavored to improve their condition.

More than anything else, though, Boyle was a devout believer in the God of the Bible, and it was his commitment to faith that drove all of his other undertakings. The foundation of Boyle’s science—and everything else he did—was a belief in the Creator God who ordained the very laws of nature which Boyle ceaselessly sought to discover.

The Father of Experimental Science

Robert Boyle was a key figure in the ‘scientific revolution’ of the seventeenth century who formed the nature and shaped the character of all modern science that was to follow. The pivotal role that he played in the reformulation of knowledge about the natural world has provided the basis of scientific developments ever since.1 As the most eminent scientist of the age, Boyle’s work profoundly influenced Sir Isaac Newton and countless other scientists who followed in his footsteps.

Boyle expanded on the empirical and quantitative approach to studying nature that had been advocated by Cardinal Nicholas of Cusa in the 1400s and Sir Francis Bacon in the 1500s, and he put their theory into practice. Investing the considerable wealth from his family estate into a laboratory suited to his empirical purposes, Boyle became the foremost pioneer of the experimental scientific method. Spending innumerable hours accumulating data about the natural world through carefully controlled experiments, Boyle meticulously recorded the results and published them so that others could replicate his findings. Embracing a philosophy of openness and transparency in publishing his results, Boyle stood in sharp contrast to the alchemists of his time, whose goal was to discover the secrets of nature in order to use them for private gain.

Boyle, on the other hand, was committed to publicly sharing his knowledge for the sake of the benefit of all humankind.2 For instance, in his work ‘Invitation to a Free and Generous Communication of Secrets and Receits in Physick’ (1655), Boyle advocated openness regarding medical discoveries and other types of scientific remedies which were typically withheld from general circulation as a sign of social exclusivity. Citing God’s self-revelation to all humankind as his key example, Boyle put forward various motivations for “public-spirited activity” and open-access science.3

Boyle was particularly ingenious in devising experiments that were aimed at revealing the secrets underlying the natural phenomena that interested him. He invented and employed new instruments that would allow him to manipulate environments. For instance, Boyle and his lab assistant and colleague, Robert Hooke (the founder of cell theory) designed an air pump capable of removing all the air from a chamber and thus creating and sustaining a vacuum. They then created a glass chamber that could withstand the negative pressure and permit observations within.

With this instrument, it was then possible to observe the effects of withdrawing air from things such as burning candles and live animals. Using this transparent vacuum chamber, Boyle performed numerous famous experiments, investigating phenomena such as respiration, disease, combustion, sound, and air pressure. He proved that air is necessary for combustion and the spread of sound and demonstrated that the pressure and volume of a gas have an inverse relationship (known as Boyle’s Law). Boyle also used experimental evidence to refute both the four-element theory of Aristotle (earth, air, fire, and water) and the three-principle theory of Paracelsus (salt, sulfur, and mercury).

Pioneer of Atomic Theory and the ‘Mechanical Philosophy’

Image: world-famous-people.blogspot.com

Many of Boyle’s experiments were aimed at testing rival theories about how the natural world worked. In particular, Boyle was interested in testing—and vindicating—the mechanical philosophy (the idea that the cosmos is like a great machine made up of matter in motion) and the view that all substances are made up of atoms (which he called corpuscles), which could, in turn, exist alongside a void, or vacuum. These two views of nature were central to the success of the scientific revolution, and it was Boyle who first brought the two traditions together, while simultaneously stressing the importance of scientific experiments. According to Boyle, it was “crucial to substantiate the theory of the mechanical philosophy with experimental observations.”4

A foundational tenet of Boyle’s philosophy of nature—which was in direct opposition to the long-held Aristotelian view—was the conviction that matter is passive, having no internal power, innate force, inherent source of motion, or substantial form beyond the primary qualities of size, shape, solidity, and motion. Boyle rejected the Aristotelian tendency to see intelligent dispositions everywhere in nature and sought to experimentally falsify Aristotelian principles such as that the elements earth, air, fire, and water have internal dispositions to move toward their ‘natural’ locations in the universe.

Boyle’s rejection of Aristotle ultimately stemmed from his understanding of the Biblical doctrine of creation. In his work, A Free Enquiry Into the Vulgarly Receiv’d Notion of Nature (1686), which enumerated some of the reasons why he found the “new science” of his day more theologically compelling, Boyle opposed the prevailing “vulgar” (or commonplace) concept of nature, ultimately derived from Aristotle and Galen.

Adherents of this vulgar view tended to personify nature, saying, for example, that “nature abhors a vacuum” or that “nature does nothing in vain.” Boyle considered such sentiments as both “pagan” and “idolatrous,” since they effectively placed an intelligent, purposive agent, “much like a kind of Goddess,” between God and the world God had made.5 Noting that the Bible contained not one “Hebrew word that properly signifies Nature, in the sense we take it in,” Boyle argued for the theological superiority of explaining natural phenomena from the purely “mechanical properties and powers” given to unintelligent matter by God at the creation, rather than by projecting human mental activities onto inert matter.6

In his pursuit of the mechanical philosophy, Boyle was also motivated by a desire to show a God-centered alternative to the atheistic mechanical materialism of Hobbes, the ancient Greek atomists, and atheistic Aristotelians (such as thinkers like Pietro Pomponazzi, who had offered a naturalistic reading of Aristotle at odds with the orthodoxy of sixteenth-century Italy). Boyle was clearly concerned with such atheistic readings of Aristotle and was “anxious to find an alternative form of natural philosophy which was more overtly theistic.”

Thus in his work entitled, “Essay of the Holy Scriptures” (1653), he appealed to “my Brethren the Chymists” as the natural opponents of both Aristotelianism and atheism.7 Since the early 1650s, Boyle had shown that mechanical philosophy was more compatible with the idea of an active Creator God than it was with atheism. Only the mechanical philosophy, Boyle believed, “clearly underscored the sovereignty of God and located purpose where it properly belonged: in the Creator’s mind, not in some imaginary ‘Nature.’”8

Boyle rejected the view that matter had inherent power beyond its mechanical properties, and he sought to demonstrate how natural phenomena could be explained in terms of the motion of particles obeying certain laws of motion which he believed God had established. In works such as The Christian Virtuoso (1744), Boyle contended that the regularities of nature are a manifestation of God’s power and that God’s will is the cause of the laws of nature. It is God who created the material bodies and God who sets them in motion and maintains them in motion through the laws of nature ordained by his decree. 9

The God Behind Boyle’s Cosmos

The single most important influence on Boyle’s life and work was his deep belief in and devotion to the God of Scripture. Boyle always understood his scientific research in theological terms and his work in chemistry, physics, pneumatics, medicine, and philosophy were all a development and fulfillment of his lifelong religious quest. Boyle affirmed that there were three true books of wisdom: the “book of scripture,” the “book of nature,” and the “book of conscience.” He thought all three were important and spent nearly equal amounts of time and energy on each.

The foundational reason why Boyle was attracted to the mechanical philosophy was that it seemed to him “only plausible in conjunction with an active, supervisory Deity.” Boyle’s passion for chemistry flowed from “the Immense Quantity of Corporeal Substance that the Divine Power provided for the framing of the Universe; and the great force of the Local Motion that was imparted to it, and is regulated in it.” 10

In Boyle’s mind, the practice of science was a form of worshipping God, and thus Boyle described himself as a “priest of nature.”11 It is “an act of Piety,” exclaims Boyle, “to offer up for the Creatures the Sacrifice of Praise to the Creator; for, as anciently among the Jews, by virtue of an Aaronical Extraction, Men were born with a Right to Priesthood; so Reason is a Natural Dignity, and Knowledge a Prerogative, that can confer a Priesthood without Unction or Imposition of Hands.”12 Because God desires us “to have his Works regarded & taken Notice of,” Boyle holds that “the study of the Booke of Nature, is one of the Ends of the Institution of the Sabbath.”13

In keeping with his view that the mechanical philosophy is a powerful ally for religion, Boyle was an outspoken advocate of the design argument. Indeed, he had a very strong interest in apologetics, which reflected a lifelong internal conversation he had in his own pursuit of God amid doubts. Boyle wrote extensively on numerous apologetic themes, and in his will he established a lectureship for “proveing the Christian Religion” to skeptics and atheists.14

A Scholar of Scripture

Image: wnd.com

Boyle revered the Bible, which he studied incessantly, and he devoted many years to learning how to understand the Bible in its original languages. Boyle first studied the ancient Koine Greek of the New Testament so fully that he could quote from the Biblical Greek as readily as the English translation. From there he went on to master Hebrew in order to read the Torah in its original language. In his pursuit of understanding the Hebrew language better, Boyle went out of his way to consult Jewish scholars and rabbis in England for advice on his own translations. Boyle also learned much from conversations with Jewish scholars and rabbis on the continent, including the great Amsterdam Rabbi Menasseh ben Israel who worked for the readmission of Jews to England.

Soon Boyle reached the point where he had not only mastered the Hebrew biblical text but could also read contemporary and ancient Hebrew commentaries on it. Boyle even wrote a Hebrew grammar. He then spent years mastering other ancient languages such as Syriac, Aramaic, and Arabic, so that he could read Biblical manuscripts in these languages and further deepen his understanding of the Bible. 15

Even though he desired for the whole world to read the Bible and was personally a devout Christian, Boyle argued for religious toleration in England and for the Jewish faith in particular. Out of a desire to communicate the message of Scripture to the world, he underwrote or otherwise aided the preparation or publication of Bible translations into other languages, including Gaelic, Irish, Lithuanian, Malay, Turkish, and Algonquian. Boyle set up a printing press where translations of the Bible and of devotional works into Algonquian were published, along with an Algonquian grammar.16 This, in turn, allowed much of the Algonquin language to be preserved for posterity.

With regard to how Scripture related to science, Boyle endorsed the classic notion, at least as old as St. Basil and St. Augustine, that “nature and Scripture are both harmonious divine revelations.” Since, says Boyle, “Right Reason and Divine Revelation [are] both…Emanations from the Father of Lights: there is no likelihood that they should contradict one another.” 17

In his view, since the biblical language was accommodated to human ignorance, it should never be placed in opposition to science. The “Book of Scripture and the Book of Science were to be read together” and understood in the light of each other. For Boyle, the cosmos was intentionally designed by God to be understood by rational creatures, and, since the universe is a manifestation of God’s power, wisdom, and might, one should study the Book of the Cosmos as an aid to salvation.

To aid posterity in this endeavor Boyle left a substantial endowment in his will to start a series of annual lectures defending the existence of God and the basic tenets of Christianity against the dangers of atheism he perceived. These “Boyle Lectures” started in 1692 and lasted steadily until 1935, after which time they were given frequently, but sporadically. Since 2005, they have been given annually once again.

A Man of Philanthropy and Conscience

Image: calmast.ie

As a man of faith and science, Boyle was also a man of deep conscience who invested much of his time, energy, and money for the alleviation of human suffering and for the betterment of humanity. For Boyle, faith without works was dead, and, as he said, “to the palace of felicity the only highway is virtue.” One road to virtue was charity, and Boyle trod this road well.

According to Boyle’s confessor Gilbert Burnet, who had substantial knowledge of his largesse and spoke of it after Boyle’s death, Boyle’s donations to the poor often exceeded one thousand Pounds Sterling per year, at least one-third of his income and the equivalent of several million dollars in today’s terms. Burnet told the large crowd at Boyle’s funeral that, “His Charity to those that were in Want” was “so very extraordinary,” because “he considered himself as part of the Humane Nature, and as a Debtor to the whole Race of Men.”18

For Boyle, the practice of science itself was another path to virtue, since he believed that science is character-forming—teaching humility, the pursuit of truth over personal gain, and the value of openness and generosity rather than secrecy. He renounced lust for power, greed, and vanity as being contrary to the character of true science. He also introduced a new line of thinking, linking the character of “the Christian virtuoso” with the actual practice of science.

“The Christian virtuoso,” said Boyle, was to be “known for personal honour and trustworthiness; devotion to one’s work as a divinely ordained vocation, even a religious duty; and reliance on the testimony of nature, not human opinion.” Also, the virtuoso “ought to place the pursuit of truth over personal gain and sensual pleasure, openness and generosity over secrecy.”19

Boyle labored to improve medicine and to make pharmaceuticals more widely available to the poor. Through data-driven empirical research, Boyle noted that chemical remedies often worked better than the Galenist practice of blood-letting and that many of Galen’s views were based on claims about human anatomy that were incorrect. 20

Boyle’s empirical approach to the study of blood was fruitful and eventually led to medical advances that now routinely save lives. Boyle distrusted physicians and thought most patients were better off not seeking a medical doctor’s treatment. Through his vast network of correspondents, Boyle would find medical recipes that he would then chemically analyze and make publicly available if safe and effective—testing many of these remedies on himself first. According to the eyewitness testimony of the Florentine natural philosopher Lorenzo Magalotti, Boyle dispatched servants throughout London, bringing effective medicines from his laboratory to the poor, free of charge.

Boyle also made public the secret of an invention of his own that would change the world—the match. In 1680 Boyle saturated some coarse paper in phosphorous and drew a stick coated with sulfur across it, creating a steady flame—and the first friction match. Boyle’s creation of a reliable and eventually safe way to easily produce fire was a major technological advancement that changed the world—and, he shared this secret because he knew it could save countless lives from sickness and cold. There were limits to this support of scientific openness, though. For example, Boyle was concerned that the publication of instructions for turning less valuable metals into gold could destabilize the world economy, and result in unchecked greed, social chaos, and violence.

Boyle deeply desired that people would “serve others instead of their own pride and lusts.”21 He contended that “the less selfish and mercenary our good actions are, the more we elevate ourselves above our own, and the neerer we make our approximations to the perfections of the Divine nature.” We all know, said Boyle, “the strong obligation, that not charity onely, bare humanity layeth upon us to relieve the distresses of those, that derive their pedigree from the same father we are descended from and are equal partakers with us, of the Image of that God, whose stamp we glory in.”22

Michael Hunter, Boyle: Between God and Science, (Yale University Press, 2009), 1.

For Boyle’s relationship to Alchemy see Lawrence M. Principe, The Aspiring Adept: Robert Boyle and His Alchemical Quest, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998); and also Lawrence M. Principe and William R. Newman Alchemy Tried in the Fire: Starkey, Boyle, and the Fate of Helmontian Chymistry (University of Chicago Press, 2002).

Hunter, Boyle: Between God and Science, 61.

Hunter, Boyle: Between God and Science, 3.

Edward B. Davis, “Robert Boyle's Religious Life, Attitudes, and Vocation,” Science & Christian Belief 19 (2007), 133.

Robert Boyle, 1744. The Works of the Honourable Robert Boyle, 5 vols. Edited by Thomas Birch. Calvin, John. 1847. Commentaries on the First Book of Moses Called Genesis, vol. 1. Edinburgh: Calvin Translation Society.), 4:368

Hunter, Boyle: Between God and Science, 83.

Edward B. Davis, “A Priest Serving in Nature’s Temple” Christian History 76, 2002.

J. E. McGuire, “Boyle's Conception of Nature,” Journal of the History of Ideas, 33:4 (Oct. - Dec. 1972), 523-542.

Hunter, Boyle: Between God and Science, 4.

Robert Boyle, Christian Virtuoso, II, Works XII, 490.

Robert Boyle, Usefulness of the Natural Philosophy, I, Works III, 203.

Davis, “The Faith of a Great Scientist: Robert Boyle's Religious Life,” Biologos.

Michael Hunter and Edward B. Davis, “The Making of Robert Boyle's Free Enquiry Into the Vulgarly Receiv'd Notion of Nature (1686)” Early Science and Medicine 1 (2), 204-271.

Hunter, Boyle: Between God and Science, 80–85.

Hunter, Boyle: Between God and Science, 131.

Boyle’s Papers 1, fol. 86, transcribed after Boyle’s death by Henry Miles on BP 7, fol. 252.

Michael Hunter, Robert Boyle, 1627-91: Scrupulosity and Science, (Boydell & Brewer, 2000) 203.

Davis, “The Faith of a Great Scientist: Robert Boyle's Religious Life,” Biologos.

Edward B. Davis, "Robert Boyle, the Bible, and Natural Philosophy" Religions 14, no. 6: 795.

Davis, “Robert Boyle, the Bible, and Natural Philosophy.”

Robert Boyle, Works, 1:3.

I liked Boyle's union of science and G-d. I have always felt that they are intertwined. I also admired his giving to poor people. The concept of being in debt to humanity is very beautiful. I have a question: Boyle evidently had an enlightened respect for G-d's creatures. Why did he put animals in that vacuum chamber? I also have a correction to the essay: Alchemists were forced to work in secret and keep their findings secrete because they would be penalized by the Inquisition. It had nothing to do with personal gain!!!