The Paleontologist Priest and Prophet of the Information Age

How Pierre Teilhard De Chardin envisioned a cybernetic future where technology would lead the human mind back to God

According to both Scripture and the contemporary scientific understanding, humans were made from the dust of the earth. The standard cosmological model holds that all matter, energy, space, and time came into existence from nothing. Starting with just hydrogen and helium, the periodic table was built up, element by element, in the fiery fusion furnaces of the first generation of stars. The death of these stars would seed the next generation of the universe with the material from which planets—and ultimately life—would be made.

As humans emerged from the terrestrial star dust through a process of complexification that began with a single cell, the history of the universe would become embodied in conscious flesh and blood. We are truly one with the universe, but are we anything else? Are we “nothing but” a meaningless mass of atoms in the pointless void, or do we have a destiny beyond the stars?

Over a hundred years ago, paleontologist, priest, and mystic Pierre Teilhard De Chardin perceived God’s fire in the equations of the cosmos. As a world-renowned geologist and paleontologist who co-discovered the hominin fossil Sinanthropus, Teilhard was a scientist of deep faith who saw an unfathomable beauty in God’s creation of life through a type of evolution beyond mere natural selection. Teilhard’s vision of God’s purposes in evolution inspired generations of biologists after him, including those who formulated the Modern Evolutionary Synthesis.

As a mystic who reflected deeply on technology, Teilhard predicted a future where intelligent memory-storing computation devices would give rise to a global network of information that would harness the power of a yet-to-come cybernetic merger of human minds with computers. Ever optimistic in his outlook, Teilhard firmly believed that as future humans crossed a new threshold of cybernetic consciousness, they would in turn become more cognizant of the reality of God, and ultimately return to community with their Creator.

Seeking a Transcendent Peace in a World of Constant Change

Born in 1881 to parents of the rural French gentry, Pierre Teilhard De Chardin was a sensitive child who loved nature and yet sought to plant his existential feet on firmer metaphysical foundations. Precociously conscious of the constancy of change, young Pierre was besought by an unsettling awareness of life’s frailty. Pierre’s earliest memory was of a lock of his own hair burning—a discovery which horrified him.

Believing that he had discovered something more permanent in metal, he began collecting objects of iron and steel. Pierre recounts how “in profound secrecy and silence” he would “withdraw into the contemplation of his ‘god of iron’…because in all of [his] childish experience there was nothing in the world harder, tougher, more durable than this wonderful substance.”1

Soon thereafter, though, he discovered that his precious objects of iron, which he first thought to be indestructible, were susceptible to rust and decay. “I can never forget the pathetic depths of a child's despair when I realized one day that iron can be scratched and can rust.” Realizing that he “had to look elsewhere for substitutes that would console” him, young Pierre embarked on a spiritual quest to find a more abiding reality.

While he had inherited a love of nature and science from his father, he had received a devout religious faith from a mother who nourished in her son a deep devotion to God, despite the influence of her great-uncle Voltaire. Religious faith offered Pierre a timeless philosophical calm amid the shifting temporal waves of natural phenomena.

As he grew older and went on to higher education, Teilhard chose to more intensely investigate both religious faith and the sciences of geology and physics. Yet, he would often feel that his two great loves—science and religion—were in conflict, and he came to worry that his enduring love for the creation might threaten his love for the Creator. Torn in two directions, Teilhard averted a crisis of faith when a spiritual mentor suggested that he should seek a deeper understanding of God precisely through a deeper understanding of the processes of Earth.

Determined to reconcile these two approaches to reality, Teilhard pursued a vocation as a Jesuit priest while at the same time continuing his studies in science. As Teilhard, through science, surrendered himself “to the embrace of the visible and tangible universe,” he learned to feel the hand of God. He reflected that he perceived, “as though in ecstasy, that through all of nature I was immersed in God.”2

A Vision of Hope in a Time of War

Image: bbc.com

As Teilhard was discovering the reconciliation of science and religion, the First World War broke out. Germany invaded Teilhard’s native France, and he immediately volunteered for service as a medic and stretcher bearer. During World War I, Teilhard participated in sixty-seven major battles (including those at the Marne, Ypres, Nieuport, Verdun, Somme, and Chateau Thierry) and was decorated three times for valor. Tirelessly attending to both the physical and spiritual needs of the soldiers in the firestorms of the most furious conflicts of the war, Teilhard assisted the dying and consoled the suffering men, bringing them a glimpse of God’s presence through his calm and fearless demeanor in the face of death.

Discharging his daily duties as stretcher bearer “under constant enemy fire without fear,” appearing to be psychologically “unscathed from all the battles he experienced” and “indifferent to the perils of life in the trenches,” Teilhard was known by his fellows as a man of inexhaustible courage.3 As his reputation for fearlessness grew, the “soldiers came to believe that he was specially protected by Divine power and grace,” and they flocked to him for comfort and strength. In the midst of terrible battles, surrounded by the constant experience of carnage, loss, and death, Teilhard affirmed:

I am writing these lines from an exuberance of life and a yearning to live; it is written to express an impassioned vision of the earth, and in an attempt to find a solution for the doubts that beset my action—because I love the universe, its energies, its secrets, and its hopes, and because at the same time I am dedicated to God, the only Origin, the only Issue, and the only Term. I want to express my love of matter and life, and to reconcile it, if possible, with the unique adoration of the only absolute and definitive God… Submerged in the tears and blood of a generation, I thank you, my God, in that you have made me a priest—and a priest ordained for War.4

Amid the blood and terror, Teilhard the soldier-priest “offered up the life of the world, and his own and that of his comrades, to the transforming power and presence of God.” Exercising his pastoral and priestly ministry to its fullest potential among all the pain, suffering, and loss of life, an overwhelming and powerful vision of humankind as truly one first emerged in Teilhard’s mind. Teilhard became profoundly and mystically aware of humanity as sharing a common origin and destiny that went beyond all its present discord, diversity, and divisions. Thus, his cry to God from the abyss of the trenches was transformed into a strong message of hope that encouraged and transformed every human soul that he encountered.

Yet even during the war, Teilhard never ceased to be a scientist. Wherever he went and whatever he did, science was never far from his mind. Whenever there was a lull in the battle and the bullets and the explosions temporarily ceased, he would use the opportunity—and risk the chance of getting shot—to collect minerals and small fossils from the sides of trenches or the craters that had been exposed by exploding bombs. During the lengthy battle of Champagne, where Teilhard was posted, he was able to collect so many valuable specimens of prehistoric fauna that he had sufficient material upon which to base his doctoral thesis after the war.

Science as a Path to Deeper Faith

After the war, Teilhard continued his education and graduated from the Sorbonne with degrees in geology, zoology, and botany. He then went on to gain his doctorate, soon distinguished himself as a geologist and paleontologist, and eventually became world-renowned through his participation and leadership in a number of groundbreaking scientific discoveries.

As the chief geologist who led the National Geological Survey of China, he was also a key researcher in the discovery and analysis of Sinanthropus, an important fossil specimen of Homo erectus that shed light on the evolutionary emergence of hominins. Teilhard likewise made significant contributions to understanding China's sedimentary deposits, establishing ages for different rock layers, and producing a geological map of the country.

At the apex of his scientific career in geology and paleontology, as he was studying fossils and hominin bones in northern China in the 1920s, Teilhard wrote that the whole material world is the setting for a profound, mystical vision of God. It is, he said, “in the world itself, as it is seen through the eyes of science, that the workings of God are most apparent.”5 Affirming the material world of science as a source of mystical spiritual illumination, Teilhard wrote:

All around us, to right and left, in front and behind, above and below, we have only to go a little beyond the frontier of sensible appearances in order to see the Divine welling up and showing through….By means of all created things, without exception, the Divine assails us, penetrates us, and moulds us. We imagined it as distant and inaccessible, whereas in fact we live steeped in its burning layers. In eo vivimus [in Him we live]. As Jacob said, awakening from his dream, the world, this palpable world, which we were wont to treat with the boredom and disrespect with which we habitually regard places with no sacred association for us, is in truth a holy place, and we did not know it.6

Teilhard understood that the human person is so much more than a mere mass of atoms. For him, everything, including the very ‘mass’ of our bodies, is a shining forth of spirit, because at the very “heart of Matter,” there is “a World-Heart, the Heart of a God.” A stone is “not just resting there on the ground; it is filled with energy, with activity, since it is made up of far-from-static atoms.”7 The ultimate source of that energy is the Creator God, who is the personal immanent heart of the boundless cosmos. God is the ultimate unity and goal, or Omega Point, of the cosmos, and it is in God that the evolution of the cosmos finds its purpose and meaning.

Teilhard described every scientist as a type of priest and he endeavored to show that the material world, the world of rocks and trees, stars and planets, plants and animals, was not the neutral subject of scientific investigation, but rather the bedrock and soil from which would spring a new vision of the holy. “The very subject matter of pure science was nothing less than a mirror in which one could see reflected the face of God.”8

Teilhard saw the universe “not as just objective matter but as suffused with psychic or spiritual energy.” As a dynamic evolving expression of God’s creative revelation, Teilhard affirmed the Cosmos as a “cosmogenesis”—an “unfolding unity” of matter, mind, intelligence, and life, where consciousness is on the rise.”9 In Teilhard’s vision, biological evolution offers compelling evidence for a new law of life, the law of increasing complexity and consciousness, where increased complexity in species corresponds to the emergence of greater sentience.

A Technological Vision of the Spiritual Future

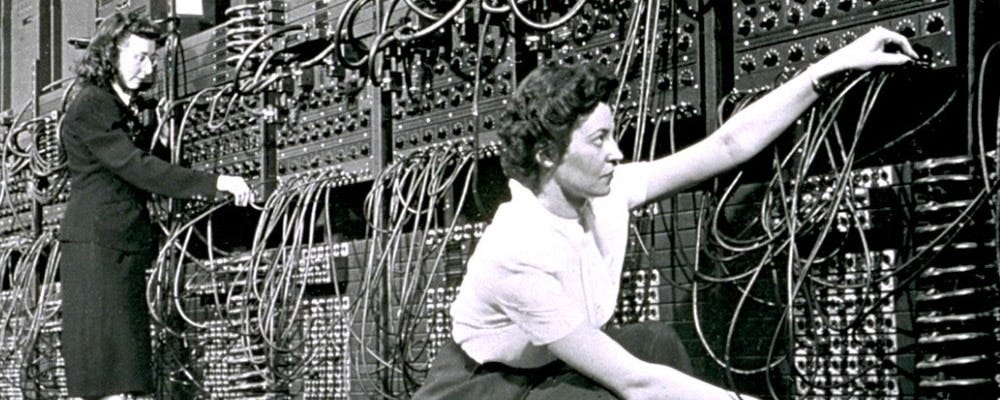

Image: hp.com

Teilhard envisioned evolution not as a random product of the “survival of the fittest” but as an emergent unfolding of cosmic laws of convergence and development that were intricately planned and providentially guided by the same Divine agency that created such laws. He believed that the evolutionary ascent of human beings would occur in two stages of “planetization”.

The first stage, characterized by God’s commandment to “Go forth and multiply,” is where life as a whole and then human life in particular multiplies and diversifies throughout the globe. This stage includes growth in both quantitative and qualitative dimensions, where consciousness and self-awareness increases among humans and other forms of life. The second stage is characterized by “unification” or “convergence” stage, where humans, through technology, would create a global network of trade, knowledge, cooperative research, and communication, which “all go into the weaving of the material support for a sphere of collective thought.” Teilhard called this future global network of knowledge “the Noosphere.”

Writing in the mid-1940s, when the construction of one of the first computers—the ENIAC –was announced, Teilhard detailed a future vision where “the structure and functioning of what might be called the ‘cerebroid’ organ of the Noosphere” would be facilitated “in the first place by the extraordinary network of radio and television communications which... already link us all in a sort of ‘etherized’ universal consciousness...and eventually by the “growth of astonishing electronic computers which will enhance the essential factor of ‘speed of thought.’”10

Through the development of more advanced computers, Teilhard predicted that humanity would embark on “the process of ‘cerebralising’ itself…on an immense scale.” Teilhard says: “Just as Earth once covered itself with a film of interdependent living organisms which we call the biosphere, so mankind's combined achievements are forming a global network of collective mind”—a collective “sphere of information.”

Writing in the 1940s in Man's Place in Nature, Teilhard explains how future computers will accomplish the instantaneous retrieval of information around the globe. Through “those astonishing electronic machines (the starting-point and hope of the young science of cybernetics), by which our mental capacity to calculate and combine is reinforced and multiplied,” he believed a “cybersphere” of global information exchange and worldwide social interaction would emerge.11

As advances in information technology and electronic communication would bring together billions of individual brains into a global network of interconnection, he believed that the emergence of this Noosphere would then lead to the next step in evolution. At this point, Teilhard believed, the human spirit—aided by computer technology—would reach beyond itself to God, “the Omega Point,” and finally return to its Creator.

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, The Divine Milieu: An Essay on the Interior Life, (Perennial Classics, 2001) xviii.

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, in Ursula King, Spirit of Fire: The Life and Vision of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (Orbis, 1998), 19.

Spirit of Fire, 51.

Spirit of Fire, 65.

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, in Charles P. Henderson, God and Science: The Death and Rebirth of Theism (John Knox Press, 1986), 88.

Teilhard de Chardin, The Divine Milieu.

Fr. Chris Corbally S.J. “Fr. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin S.J.” Thinking Faith (22nd January 2014).

Teilhard de Chardin, in God and Science, 89.

Teilhard de Chardin in The Cosmic Pilgrim, 16.

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, The Future of Man (Harper & Row, 1964), 173-4, 180.

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, Man's Place in Nature: The Human Zoological Group (Harper & Row, 1966).

Whenever I encounter people writing on De Chardin it is always critical. Fascinating piece.

How VISIONARY! Today we can Google all sorts of things. I access this essay via my laptop computer. He got it right! 100% We must, however, be cautious and not let AI take over.