How Matter Emerged From Eternal Life

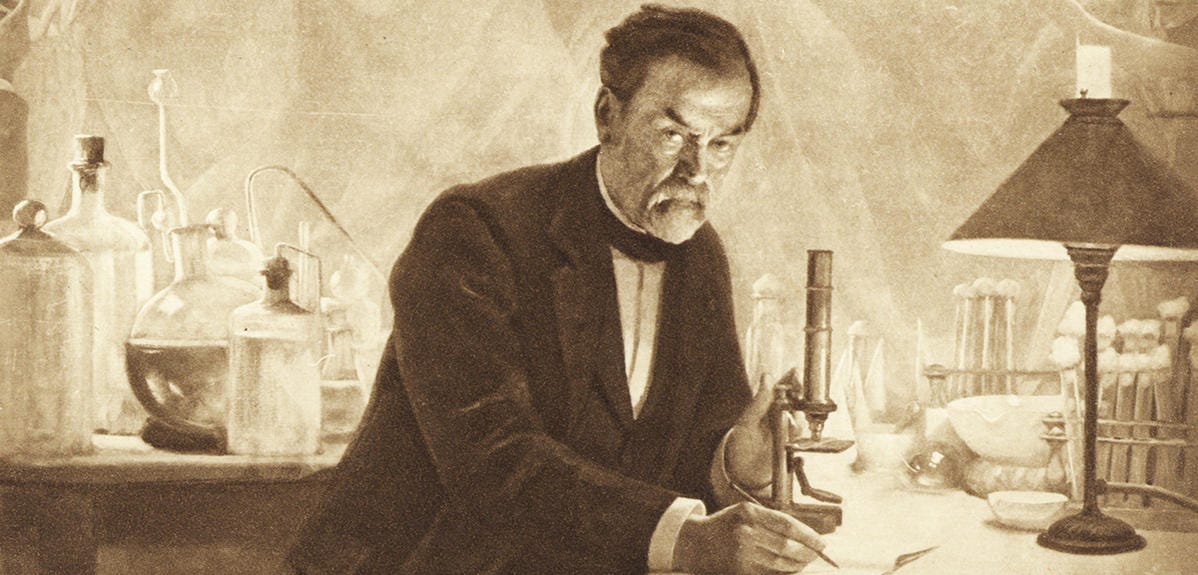

Louis Pasteur, the Spontaneous Generation Debate and the Origin of Germ Theory

Image: Louis Pasteur, lejournal.cnrs.fr

Throughout most of human history, the origin of diseases, pestilences, and plagues remained a mystery. In the late 1800s, the French chemist and microbiologist Louis Pasteur came to the conclusion that microorganisms cause such widespread diseases. The Father of immunology, germ theory, microbiology, and cell theory, Pasteur was likewise the first to formulate a biological and chemical theory of global ecosystems in concrete empirical terms.1 Developing the germ theory of disease, pasteurization, and vaccination, Pasteur’s profound scientific insight and ingenious applications led to a deep and lasting social impact and saved millions of human and animal lives.

Yet Pasteur was also a devout Catholic who embraced the Biblical vision of God as the Creator of life. He always held that “science brings men nearer to God.”2 Pasteur’s desire to heal people through the applications of science was rooted in Biblical compassion, and his scientific campaign to refute spontaneous generation was grounded in a deep conviction that atheistic materialism was wrong. Life does not come from dead matter, insisted Pasteur. Rather, life comes from life, and matter ultimately comes from the Eternal Life.

Discovering Chemical Chirality

Image: stock.adobe.com

Born in 1822 to a humble, religiously devout, and loving family, Pasteur developed a love of science early in life. He studied chemistry at the renowned École Normale Supérieure in Paris and obtained a doctoral degree in chemistry. After completing his education, Pasteur began studying crystallography and conducted his early research on the crystalline residues that form inside wine barrels. He was puzzled by the fact that tartrates and paratartrates behave differently toward polarized light because these compounds display identical chemical properties.

Separating these crystals manually, he found that they exhibited right and left asymmetry and that a balanced mixture of both right and left crystals was optically inactive. Pasteur concluded that this was caused by a molecular asymmetry, or chirality, within the crystals. Over the next ten years, Pasteur continued to investigate chirality in organic substances and became convinced that such mirror-image asymmetry was one of the fundamental characteristics of living matter.3 Pasteur thus laid the foundations for the field of science known as stereochemistry.

Introducing the Germ Theory of Disease and Contagion

At the same time that he was investigating chirality in the crystalized residues of wine barrels, Pasteur was asked by local brewers to investigate why certain batches of wine and beer would turn sour while others of the same harvest would remain fresh. Pasteur visited numerous breweries and studied fresh and spoiled samples under his microscope. He discovered that freshly brewed beer contained microscopic round bodies (yeast), whereas spoiled beer had elongated rod-shaped bodies.

From this observation, Pasteur hypothesized that fermentation was actively initiated by these tiny microscopic organisms, or microbes, rather than being a lifeless chemical reaction. He postulated that yeast produced the agreeable taste of beer and wine by normal fermentation (transforming sugar to alcohol), while rod-shaped bacteria soured the batch through other metabolic processes.4

Pasteur soon applied his observations regarding the role of microbes in beer and wine fermentation to the cause of putrefactions of wounds, the infection of boils, and deadly fevers. In 1864, Pasteur proposed the “Germ Theory of Disease,” postulating that infectious diseases were caused by microorganisms. Furthermore, he deduced that such microbes, as causes of infection, did not arise spontaneously but were transported through the air and other contaminated objects.

Pasteur consequently encouraged physicians at the French Academy of Medicine to “use none but perfectly clean instruments” and to “clean [their] hands with the greatest of care.”5 Pasteur also invented—together with microbiologist Charles Chamberland—and promoted the medical use of the autoclave, a machine that sterilizes surgical instruments by employing heat and steam under pressure to kill harmful bacteria, viruses, fungi, and spores on items that are placed inside a pressure vessel.

Producing the Process of Pasteurization

Image: tonsoffacts.com

Having discovered the key to removing microbes from medical instruments Pasteur likewise found that gently heating wine would kill all the microbes present and that such treated wine, when sealed from the atmosphere, would stay fresh and preserve its taste. Developing scientifically informed techniques for the control of beer fermentation, Pasteur devised a method for the brewing industry that would enable them to manufacture beer in such a way as to prevent deterioration of the product during long periods of transport or storage.

Applying his knowledge of microbes and fermentation to the wine and beer industries in France, Pasteur saved the industries from collapse due to problems associated with production and contamination that occurred during export. Public health improved as Pasteurization was applied to numerous foods and beverages to reduce spoilage and eliminate pathogens for consumers. This was particularly the case with the application of Pasteurization to milk, which greatly reduced infant mortality.6

Pioneer of Immunology and Vaccines

Pasteur knew of Edward Jenner's use of the principle of vaccination against smallpox a century earlier and extended Jenner's work to develop vaccines against avian cholera, anthrax, and rabies. In 1877, Pasteur began investigating avian cholera and identified Pasteurella multocida as the bacterium that causes this disease. Then, in 1879, due to a fortuitous series of events, he discovered that, over time, cultures of this bacterium experienced a decrease in virulence. Before leaving for an extended journey, Pasteur instructed an assistant to inject some chickens with fresh cultures of P. multocida, but the assistant forgot to do so.

Upon Pasteur’s return, the assistant then injected the chickens with the cultures in glass tubes sealed only with a cotton plug that had been left in the laboratory for a month. To Pasteur’s surprise, these chickens developed mild symptoms and fully recovered. Pasteur then injected the recovered chickens with a fresh bacterial culture of P. multocida, expecting them to develop the disease, but the birds remained healthy. Pasteur deduced that exposure to oxygen caused the loss of virulence (which he called attenuation) and subsequently validated this hypothesis through a series of controlled experiments.7

Having established that weakening bacterial cultures with chemicals or exposure to air decreased the agent's virulence, Pasteur then extended such experiments toward developing a vaccine against anthrax. Through a series of public experiments, Pasteur showed that sheep inoculated with attenuated bacterial cultures developed only a mild illness and, upon recovery, became resistant to anthrax.

Having successfully developed a vaccine for anthrax, Pasteur moved on to conquer the dreaded disease of rabies. Suspecting that the brain and spinal tissue of the infected animal harbored the microbial rabies agent, Pasteur took sections of spinal cord from infected rabbits and suspended these inside flasks within a moisture-free atmosphere. He found that virulence gradually declined until finally disappearing. He then injected this attenuated material into dogs and found that this protected the dogs when they were exposed to rabies.8

Using this method, Pasteur had inoculated approximately 50 dogs when, on July 6, 1885, a desperate mother brought her nine-year-old son, Joseph Meister, to Pasteur’s laboratory. Joseph had been bitten at least 14 times by a rabid dog two days earlier, and his death from rabies seemed inevitable. After consulting with medical colleagues, Pasteur applied the methods that he had used on dogs and inoculated the boy with material from a rabid rabbit's spinal cord that had been dehydrated for 15 days. He then continued to administer a series of vaccinations.

The child did not develop the disease and fully recovered. Having saved Joseph’s life, Pasteur was soon approached with another case of rabies in a human and was successful in preventing the disease by using the same method. This marked the birth of the first successful vaccine against rabies and the beginning of a new era in preventing infectious diseases.

The Spontaneous Generation Debate & Pasteur’s Critique of Atheist Materialism

Image: nordlittoral.fr

The idea of spontaneous generation, that living things can originate suddenly from nonliving matter, has a long history that ultimately goes back to Aristotle. During the time of Pasteur, the debate over whether or not spontaneous generation, coined abiogenesis by Thomas Henry Huxley, continued to occur was inextricably intertwined with the public controversy over atheistic materialist interpretations of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution—interpretations which Darwin himself did not share.9

The first translation into French of Darwin’s Origin of Species—by atheist materialist and early feminist activist Madame Clémence Royer—made this connection clear as she prefaced her translation with a lengthy diatribe against the Biblical concept of creation and explained that “it is in vain that Mr. Darwin affirms that his system is in no way opposed to the Divine idea.”10 In France, in the mid-1800s, to accept the concept of spontaneous generation was the equivalent of accepting atheism and materialism and of rejecting geological evidence showing the non-interrupted “chain” of living beings.11

Accepting spontaneous generation was likewise seen as a rejection of the germ theory of disease. Consequently, “disproof of spontaneous generation was thought by many to imply the victory of the germ theory.”12 Convinced that his “germ theory could not be firmly substantiated as long as belief in spontaneous generation persisted,”13 Pasteur arose to meet the skeptics of both Biblical creation and germ theory in scientific battle. Pasteur saw himself as “defending religious and moral orthodoxy against atheism and materialism by demonstrating that the evidence claimed to support the doctrine of spontaneous generation is built on experimental mistakes.”14 To this end, Pasteur exclaimed, “What a conquest for materialism if it could claim to be based on the proven fact of matter organizing itself into living beings…Why then the idea of a creator God?”15

Pasteur conducted his famous swan-neck flask experiment to experimentally falsify the idea of spontaneous generation. Preparing a nutrient broth, Pasteur placed equal amounts of the broth into two long-necked flasks—one with a straight neck and the other with the neck bent in the shape of an “S.” Boiling the broth in each flask to kill any living matter in the liquid, Pasteur left the sterile broth samples to sit, and exposed them to air at room temperature for several weeks. Pasteur observed that the broth in the curved-neck flask had not changed color, while the broth in the straight-neck flask was discolored and cloudy.

He reasoned that contaminating microbes in the air fell unobstructed into the broth of the straight-necked flask, while such microbes got caught in the “S” of the other flask, thus never reaching the broth. The source of new life was thus the outside air and not the nutrient broth itself. Otherwise, both broths would have become equally cloudy and full of microbes. Having empirically established the principle “omne vivum ex vivo” (that “life only comes from life”), Pasteur reflected:

I have been looking for spontaneous generation for twenty years without discovering it. No, I do not judge it impossible. But what allows you to make it the origin of life? You place matter before life and you decide that matter has existed for all eternity. How do you know that the incessant progress of science will not compel scientists to consider that life has existed for all eternity, and not matter? You pass from matter to life because your intelligence of today cannot conceive things otherwise. How do you know that in ten thousand years, one will not consider it more likely that matter has emerged from Eternal Life?16

René J. Dubos, Louis Pasteur: Free Lance of Science (Little, Brown, 1950).

R. Vallery-Radot, The life of Pasteur. 2 vols. Translated by R. L. Devonshire (Archibald Constable, 1901/1902).

Ghislaine Vantomme and J. Crassous, “Pasteur and chirality: A story of how serendipity favors the prepared minds,” Chirality 33 (10), 597-601, 2021.

Gerald L. Geison, The Private Science of Louis Pasteur (Princeton University Press, 1995), 106 ff.

Emile Duclaux, Pasteur; The History of a Mind, (W.B. Saunders company, 1920), 267.

Russell Currier, “Pasteurisation: Pasteur’s greatest contribution to health” The Lancet, Vol 4 (March 2023).

David A. Montero, et. al., “Two centuries of vaccination: historical and conceptual approach and future perspectives,” Frontiers in public health, 2023

Rino Rappuoli, “1885, the first rabies vaccination in humans,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, PNAS Vol.111, (2014-08).

James E. Strick, Sparks of Life: Darwinism and the Victorian Debates Over Spontaneous Generation (Harvard University Press, 2009).

Florence Raulin Cerceau, “French Views on the Origin of Life Combined with Theological Thoughts: From Louis Pasteur (1860) to Edmond Perrier (1920)” in Divine Action and Natural Selection : Science, Faith, and Evolution, Joseph Seckbach and Richard Gordon eds. (World Scientific, 2008).

Cerceau, “French Views on the Origin of Life.”

Strick, Sparks of Life.

Guy Bordenave, “Louis Pasteur (1822–1895)”. Microbes and Infection , 5(6), 553–560 (2003); Nils Roll-Hansen, “Experimental Method and Spontaneous Generation: The Controversy between Pasteur and Pouchet, 1859-64,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, Volume XXXIV, Issue 3, (July 1979), 273–292.

Nils Roll-Hansen, “Louis Pasteur—A Case Against Reductionist Historiography,” British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 23 (4):347-361 (1972), 360.

Roll-Hansen, “Louis Pasteur—A Case Against Reductionist Historiography,” 360.

Cerceau, “French Views on the Origin of Life,” 264; Also in Dubos, Louis Pasteur : Free Lance of Science, 396.

Great overview of Pasteur's life and thought. The final quotation, in particular, gets to the heart of the rationale behind vitalism. You may like reading my article here: https://doi.org/10.1080/19420889.2022.2071102

Excellent essay by Dr. Moritz. It provides a historical look at this great scientist and addresses our modern-day vaccine controversy. I like that it deals with concrete biological science and yet is very accessible instead of being arcane. May all of our vaccines survive the next 4 years.