Will the Cosmos Resurrect After Its Heat Death?

On Lord Kelvin: The spiritual scientist who discovered energy.

Scottish physicist, mathematician, and engineer William Thomson was one of the greatest scientists of the 19th century. A pioneer who contributed significantly to the unification of physics and made groundbreaking discoveries in physics and electromagnetism, Thomson laid the groundwork for the physical science of thermodynamics, formulated the first and second laws of thermodynamics, and was the first scientist to articulate the hypothetical concept of dark matter.

The “unquestioned leader of science and technology” in his age,1 Thomson was also an ingenious inventor who held 70 patents for inventions by the end of his career—many of which are still used today.2 Thomson, who would later be ennobled as Lord Kelvin for his scientific discoveries, devised numerous instruments to improve navigation and safety at sea, developed more accurate mariner's compasses, and established global telecommunications by creating the first transatlantic telecommunications cables.

Applying his work in thermodynamics, Thomson created an absolute temperature scale, proposing the concept of absolute zero as the starting point for this scale. Having played a leading role in developing the concept of entropy, which defines an “arrow of time” on a universal scale, Lord Kelvin argued against James Hutton and Charles Lyell’s Uniformitarian Geologic Eternalist theory that the Earth is infinitely old with “no vestige of a beginning and no prospect of an end.”3

Through all of his scientific work, Thomson was deeply inspired by his Biblical faith. “Lord Kelvin’s religious convictions about a created universe—with a beginning and an end—were decisive in the development of the Second Law of Thermodynamics.”4 His faith-inspired scientific work on the thermodynamic history of the Earth convinced geologists of the time—and many others—that the Earth was not infinitely old but had a true beginning and an unrepeatable linear geologic history. According to Kelvin, science was in no way at war with faith. Indeed, said Kelvin, quite the opposite was the case: “I believe that the more thoroughly science is studied, the further does it take us from anything comparable to atheism.”5

A Child Prodigy in Science and Mathematics

Born in 1824, William Thomson grew up in a context where scientific understanding was nourished by a devout Biblical faith. His father, James Thomson, was a devout Presbyterian Christian and a professor of mathematics at the University of Glasgow. Since his mother died when he was only six years old, William was raised primarily by his father—a gifted teacher who personally undertook his children’s education and employed every opportunity to edify his children about the world of nature as God’s good creation. William’s older sister recorded an early memory of their father taking the opportunity of a fierce storm to teach his children about winds and barometric pressure. She writes:

A hurricane of wind and rain rushed fiercely into the room, and…every window in the front of the house was shattered. The kitchen chimney…was blown down and fell through the roof in ruins on the kitchen floor. The next day…I have the most distinct remembrance of my father carrying me in his arms, wrapped in a large shawl, from one darkened room to another—for…the storm was still raging, though with abated fury. First he took me to the door of the kitchen and let me see the mass of brick and slate on the floor, and bade me look up through the hole in the roof at the angry clouds scudding across the sky. Next he took me into the dining-room and showed me the mercury heaving in the tube of the barometer, telling me that the heaving was caused by the wind. Then he opened the instrument and showed me the cup of mercury in which the base of the tube was immersed…6

As a student of his father, young William was taught the most recent advances in mathematical scholarship before they ever appeared in university curricula, and at age ten, he enrolled as a student at his father’s university. At age sixteen the young Thomson began publishing articles in the areas of mathematics and science. His first paper (which was published in The Cambridge Mathematical Journal under a pseudonym for the sake of propriety) corrected Edinburgh University Professor of Mathematics Phillip Kelland’s misunderstanding of Fourier’s book on Euclidean spaces—a book which Thomson had read in the original French and quickly mastered. At the time of William’s first paper, there was no firm physical understanding of what heat actually was. However, as William became inspired by Fourier’s work, he proposed that one could still describe the behavior of heat mathematically without knowing precisely what heat physically is.

After immediately publishing another paper on mathematics under the same pseudonym, P.Q.R., William published a more substantial scientific paper where he made groundbreaking connections between the mathematical theories of heat conduction and electrostatics, demonstrating that similar mathematical equations could be used to describe both phenomena.7 Thomson’s idea of unifying previously unrelated areas of science through mathematics would later provide the groundwork for James Clerk Maxwell's theory of electromagnetism.

William continued his mathematical and scientific education and research at Cambridge University, starting in 1841, and soon published another groundbreaking paper where he mathematically developed Michael Faraday’s theory that electric induction occurs through an intervening medium or “dielectric,” and not through a mysterious and incomprehensible “action at a distance.” In the same paper young William also devised the mathematical technique of representing electrical images—a technique that would become an essential element in solving problems of electrostatics. Encouraged by William’s pseudonymous paper, Faraday began research in September 1845, which would lead to the discovery of the Faraday Effect (establishing that light and magnetic—and thus electric—phenomena were related).

Thomson’s Laws of Thermodynamics

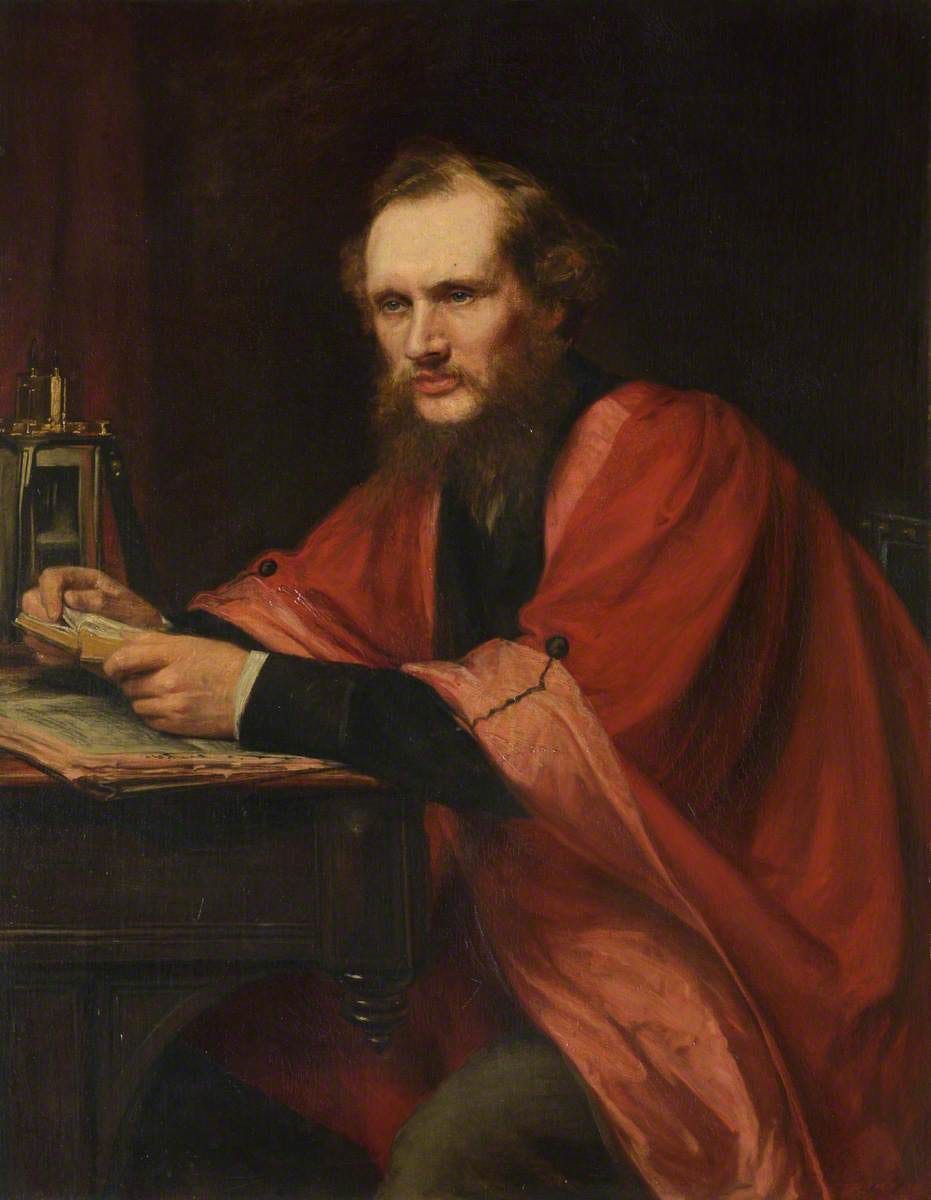

Image: Lord Kelvin, artuk.org

In 1846, at the age of 22, Thomson was appointed by unanimous election of the faculty to the Chair of Natural Philosophy at the University of Glasgow. As a professor of science, Thomson created a laboratory and “apparatus room” with state-of-the-art instruments to provide his students with “hands-on” research opportunities in conjunction with the scientific lectures that he gave in the adjoining classroom. Thomson thus spearheaded the laboratory component of scientific education that would become a universal standard in succeeding generations. In the late 1840s, Thomson continued his study of heat and remained deeply perplexed by what appeared to be the irrecoverable nature of that heat. He first introduced the term “thermodynamic” in 1849 and would later solidify “thermodynamics” as the name of the new field of physics in 1854.8

In 1851, Thomson published two propositions—the first regarding the equivalency of work and heat (in response to the work of James Joule) and the second regarding Nicolas Carnot's concept of a perfect engine.9 Combining Carnot's theory with Joule's thesis on energy conservation, Thomson concluded that work “is lost to man irrecoverably though not lost in the material world.” While “no destruction of energy can take place in the material world without an act of power possessed only by the Supreme Ruler, yet transformations take place which remove irrecoverably from the control of man sources of power which … might have been rendered available.”10 In other words, said Thomson, only God can ultimately create or destroy energy (universally speaking) but human beings and other entities within God’s creation can make use of transformations of energy.

This reasoning crystallized in what later became the canonical “Kelvin statement of the second law of thermodynamics,” first enunciated by Thomson in 1851.11 Thomson’s two laws of thermodynamics meant that physics could be rewritten in terms of energy, and they began a fundamental revolution in physics that has never been eclipsed. Indeed, Thomson’s laws have stood the test of time to the point where many physicists today have remarked that “everything we know in science may be wrong, except the first and second laws of thermodynamics.”12

The Arrow of Time in a Dynamically Evolving Created Universe

In Thomson’s new understanding of the universe, the focus was “energy”—a term introduced by Thomson that achieved public prominence for the first time. Thomson’s fundamentally historical cosmos was governed by the dual principles of the conservation of energy (after the initial creative act of God) and the dissipation (or transformation) of energy. As Thomson explained: “Since it is most certain that the Creative Power alone can either call into existence or annihilate mechanical energy, the ‘waste’ referred to cannot be annihilation, but must be some transformation of energy.”13

Thomson viewed his dynamical theory of energy “as a cosmological, and indeed theological, principle.”14 Irreversible transformations of energy amounted to a universal statement that “Everything in the material world is progressive” and that “the material world could not come back to any previous state without a violation of the laws which have been manifested to man, that is, without a creative act or an act possessing similar power.”15 A cyclical cosmos was no longer an option. Nor was the steady-state geological uniformitarianism of James Hutton and Charles Lyell. Thomson “rejected eternal recurrence”—both cosmic and geological—“as incompatible with the second law of thermodynamics.”16

The irreversible arrow of time introduced by Thompson’s new science of thermodynamics meant that all things had a beginning and all things would have an end. The cosmos was physically evolving according to what Thomson argued was a Divine plan that would end in God’s resurrection and re-creation of the cosmos beyond the final “heat death” of the current universe. “Thus,” wrote Thomson, “we have the sober scientific certainty that heavens and earth shall ‘wax old as doth a garment;’ [Psalm 102:26] and that this slow progress must gradually, by natural agencies which we see going on under fixed laws bring about circumstances in which ‘the elements shall melt with fervent heat.’ [2 Peter 3:10] With such views forced upon us by the contemplation of dynamical energy and its laws of transformation in dead matter, dark indeed would be the prospects of the human race if unillumined by that Light which reveals ‘new heavens and new earth.’ [2 Peter 3:13].”17

Brian Pippard, “Forword” in Kelvin: Life, Labours and Legacy, Eds. Raymond Flood, Mark McCartney and Andrew Whitaker (Oxford University Press, 2008), v.

Matthew Trainer, “The patents of William Thomson (Lord Kelvin)” World Patent Information 26 (2004): 311-317.

See Martin Rudwick, Earth’s Deep History: How It Was Discovered and Why It Matters, (University of Chicago Press, 2016) 72.

J Sánchez-Cañizares, “The Impact of Religion on Kelvin's Physical Insights” FORUM Volume 4 (2018)

S.P. Thompson, The Life of William Thomson, Baron Kelvin of Largs (2 vols.) (London: Macmillan, 1910), 1103.

Elizabeth Thomson King, “The Dawn of Memory” in Lord Kelvin's Early Home (London: Macmillan, 1909), 22-23.

William Thomson, “On the Uniform Motion of Heat in Homogeneous Solid Bodies, and its Connection with the Mathematical Theory of Electricity’, Cambridge Mathematical Journal (1842)

Helge S. Kragh, Entropic Creation: Religious Contexts of Thermodynamics and Cosmology (Science, Technology and Culture, 1700-1945) (Ashgate, 2008), 24.

Crosbie Smith, “Thomson, William, Baron Kelvin (1824–1907), mathematician and physicist.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Crosbie Smith and M. Norton Wise, Energy and Empire: A Biographical Study of Lord Kelvin (Cambridge University Press, 1989), 329.

“It is impossible, by means of inanimate material agency, to derive mechanical effect from any portion of matter by cooling it below the temperature of the coldest of the surrounding objects” W. Thomson, “On the Dynamical Theory of Heat, with numerical results deduced from Mr. Joule's equivalent of a Thermal Unit, and M. Regnault's Observations on Steam". Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. XX (part II) (March 1851): 261–268, 289–298. Also published in W. Thomson, “On the Dynamical Theory of Heat, with numerical results deduced from Mr. Joule's equivalent of a Thermal Unit, and M. Regnault's Observations on Steam” Philosophical Magazine 4. IV (22): (December 1852). 8–21.

David Saxon, “In Praise of Lord Kelvin” Physics World, (17.12.2007), 2.

William Thomson, “On a Universal Tendency in Nature to the Dissipation of Mechanical Energy,” Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 3, 139–142. (1857) 1.511.

Smith and Wise, Energy and Empire, 330.

Smith and Wise, Energy and empire, 330.

Kragh, 136.

Crosbie Smith, The Science of Energy: A Cultural History of Energy Physics in Victorian Britain (University of Chicago Press, 1998), 185.

Thank you for this rich exploration into the life of William Thompson; I had no idea of the magnitude of his life. He's an example of avoiding both scientism and fideism (as you advocate for in your book).

I believe an open mind must ultimately reach a point of acknowledging existence itself as an unexplained miracle. We often wrap that miracle in the context of our cultural religion for closure, because grappling with an unsolvable conundrum can be an existential threat to the ego. But our spiritual explanations of the mystery are wonderful. Everyone needs to explain (or contain) it in their own framework.

Thompson conceptualized amazing principals based on his balanced perspective of religion and science. Interesting also that one can start strictly on the scientific side and move toward spirituality:

“The more I think about [any theory], the less plausible it becomes. One starts as a materialist, then turns into a dualist, then a panpsychist, then an idealist.”

~David Chalmers