When Compassion Met Reason

How Basil of Caesarea and Gregory of Nyssa Planted the Seeds of Our Present Age

Image: Basil of Caesarea, fivebooksforcatholics.com

We tend to take our Modern world for granted—as if our commonly cherished values and cultural institutions have always existed or are eternally self-evident or self-explanatory. However, our modern ways had a beginning, and that beginning commenced when there was enough of a clear break with preceding values and institutions that were clearly not modern. Modern values—such as human rights, the assumption that all human life has equal worth, and the importance of compassion for the weak and suffering—did not exist among the ancient Mesopotamians, Greeks, or Romans.

Indeed, the world of the Babylonians, Assyrians, Greeks, and Romans was, by our Modern standards, a place where profound cruelty and violence were commonplace, where the poor and weak were viewed with contempt rather than compassion, and where the enslavement of social inferiors was casually conventional and morally unquestioned. Modern science—characterized by the concept of Laws of Nature, the rationality and intelligibility of material reality, the physical unity of the cosmos, and the rejection of Aristotle’s physics likewise had no place among the ancient Mesopotamians, Greeks, or Romans.

The modern approach to medicine and healthcare was similarly absent. The first place in history that one sees the ensemble of values that undergird modern ethical values, modern science, and modern medicine is in the life and work of two prolific, ingenious, and influential brothers who lived in 4th-century Byzantine Cappadocia—Basil of Caesarea and Gregory of Nyssa.

The Beginning of Modern Science

The seeds of modern science were sown when Basil of Caesarea first merged the ancient Jewish concept of the Laws of Nature with the Ancient Greek philosophical tradition of rational inquiry in a work known as The Hexaemeron. Making the crucial connection between the Greek rational tradition and the Hebrew laws of nature, Basil critiqued the physics of Aristotle on a number of key fronts. Rather than explaining the behavior of the elements (Earth, Air, Fire, Water, and Ether) as acting in accordance with their natural essences, he understood the motion of physical objects in terms of natural laws.

Basil rejected the existence of the element ether—which Aristotle thought was responsible for circular motion in the incorruptible heavenly realm of the stars—and argued instead that the heavens are corruptible and changeable in the same way that the earth is. Instead of having one type of explanation for the mechanics of objects on earth and another set of explanations for the mechanics of objects among the stars, Basil argued that the same laws of physics should apply to both.

This meant that the whole cosmos shared the same physical laws and that we could, in principle, understand the laws and elements of the whole universe simply by investigating them here on the surface of Earth. In other words, Basil argued that “the entire universe is subject to a single code of law which was established along with the universe at the beginning of time.”1

Basil also replaced the concept of Aristotelian teleological essences (such as that the element Fire by its nature goes up and that the element Water goes down) with a revolutionary physical concept that would eventually be known by the name “inertia”. Basil applied this concept both to individual objects and to the entire universe and believed that “nature, once created and put in motion, evolves in accordance with the laws assigned to it without interruption or diminishment of energy.”2

Rejecting Aristotle’s understanding of the stars as living divine beings, Basil explicitly asserted that “the heavens are not alive…nor is the firmament to be thought to be a sensitive living thing.”3 This assertion subsequently allowed the stars and other celestial events to be understood according to the laws of nature rather than as voluntary motions. Because human reason is in some way a reflection or image of that same lawfulness or reason that governs the world, the laws and operations of the world can subsequently be understood—even if the ultimate origin of the universe is beyond human understanding. As the first in a series of criticisms of Aristotle that would last for 1700 years, Basil’s Hexaemeron started a cascade of insights that would eventually give rise to fully modern (post-Aristotelian) science by the mid-1800s.

The Beginning of Modern Medicine

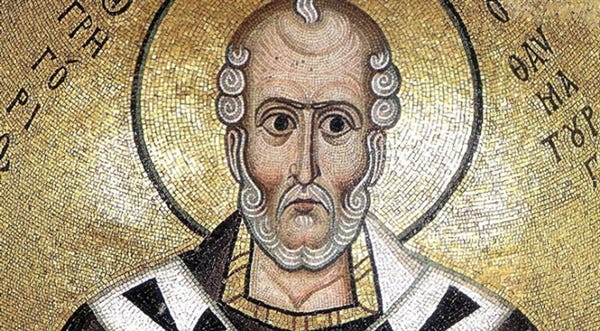

Image: Gregory of Nyssa, fatherlawrence.com

While Basil of Caesarea was trained in the Classical Hippocratic understanding of medicine, he went beyond that to develop a practical approach to medicine that would stand the test of time. In his various works, Basil showed his understanding of the deep roots of disease through contagion, discussed various natural remedies provided by medicine, and argued that the science of medicine is a gift from God, remarking that “to reject entirely the benefits to be derived from this art is the sign of a petty nature.”

Basil taught that followers of God should actively and eagerly pursue the systematic practice of healing through medicine. He believed that for every illness that exists, God created a plant, mineral, or animal to heal it and that God has also given human beings the intelligence to find and apply these remedies. All healing ultimately comes from God, and a physician who heals through medicine is participating in the work of God.

To facilitate the practice of medicine, around 370 Basil founded and maintained the earliest known hospital, which came to be known as the Basileias. Basil’s hospital—a large multi-winged complex outside of Caesarea—was the first public institution devoted to free care of the sick, the first institution that focused on medical research, the training of doctors and nurses, and holistic patient care, and the first to provide inpatient treatment that intentionally destigmatized illness.

His hospital employed a regular live-in medical staff who provided aid to the sick and medical care in the tradition of both secular Graeco-Roman medicine and Basil’s own practical approach based on his philosophy of science grounded in laws of nature. The philosophy behind Basil’s house of healing was that all patients had dignity and value because they equally bore the image and likeness of God. In the words of his brother Gregory, the Basileias was a place “in which disease is investigated and sympathy proved.”4 Basil’s “innovative type of health care system” provided a template for the earliest hospitals that arose in the following centuries and continue to this day.

The Beginning of Modern Values

For Basil and his brother Gregory, the sick and the poor deserve compassion because all human beings share a common kinship and all are created in the image of God. On the basis of this belief, Gregory anticipates the Enlightenment thinker John Locke by over a thousand years by arguing that all humans have dignity and are created with equal, intrinsic value. This conviction regarding the radical equality of humanity led Gregory to champion abolitionism and to become the first person in history to issue a “fierce, unequivocal, and indignant condemnation of the institution of slavery.”5

As an Eastern Christian Bishop, Gregory exhorted all those under his authority to emancipate their slaves. He argued that “legal slavery was illegitimate and against God, and therefore had to be abolished.”6 With extraordinary rhetorical intensity Gregory treats slavery not as a luxury that should be only temperately indulged in, nor as an unfortunately necessary domestic economy that may be abused by brutal slave-owners (as did the Stoic philosophers), but rather as “intrinsically sinful, opposed to God’s actions in creation, salvation, and the church, and essentially incompatible with the Gospel.”7 While Gregory’s challenge would take centuries to come to fruition, the conceptual seeds that he planted would eventually take root and would grow into an abolitionist movement that would eradicate slavery in the Modern age.

Christopher B.Kaiser, Creation and the History of Science, (Grand Rapids, Eerdmans, 1991) 6.

Christopher B. Kaiser, Creational Theology and the History of Physical Science: The Creationist Tradition from Basil to Bohr (Brill, 1997), 18.

Richard C. Dales, “The De-Animation of the Heavens in the Middle Ages” Journal of the History of Ideas, 41:4 (Oct.- Dec., 1980), 553.

Gary B. Ferngren, Medicine and Health Care in Early Christianity (John Hopkins University Press, 2009), 125.

David Bentley Hart, “The ‘Whole Humanity’: Gregory of Nyssa’s Critique of Slavery in Light of His Eschatology,” Scottish Journal of Theology 54.1 (2001): 51-69.

Ilaria Ramelli, Social Justice and the Legitimacy of Slavery: The Role of Philosophical Asceticism from Ancient Judaism to Late Antiquity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).

David Bentley Hart, “The ‘Whole Humanity’: Gregory of Nyssa’s Critique of Slavery in Light of His Eschatology,” Scottish Journal of Theology 54.1 (2001): 51-69.

This history lesson was fascinating. I loved the quote at the end by Gregory. To this day, there are people who advocate the dignity of human life because it is still neglected so very often. Thank you for sharing this knowledge and understanding.

Excellent summary of faith and reason in the West, but understanding of the rationality of the cosmos and profound ethical values (as manifest in 3rd century BC King Ashoka's establishment of hospitals, schools, and other means for the uplift and well being of all) existed in India at least 3000 years ago.