The Thankfulness Circuit

Sustaining Gratitude’s Positive Effects.

Whether we credit God, a person, or nature, in order to keep gratitude alive, we need to connect gratitude back to its source. Otherwise, just as electricity lacks a charge until a circuit is complete, our feelings of gratitude aren’t truly alive unless we articulate them to the giver. For example, Maria, my wife of thirty-plus years, possesses many strengths and talents, and one of them is her uncanny ability to find a gift that resonates with the lucky recipient. And sometimes, that fortunate person is yours truly.

The OM Negative

One afternoon she called me from our kitchen and told me that she’d purchased a used guitar for our son, Isaac. “Can you put some strings on it?” she asked. I strolled into his bedroom, and sure enough, a worn cardboard and vinyl case sat on the bed. I’ve seen dozens of these cases over the years, and I knew this one could only hide a thrift-shop special or some other bowed-neck misfit worth a hundred dollars at most. As I began to open the case, I thought, “Too bad Maria went and bought this piece-of-crap guitar without consulting me.”

But what was inside stunned me: the most beautiful acoustic guitar I’d ever seen, a jet-black Martin with white herringbone trim and an inlaid ivory neck, straight from some Johnny Cash dream. The guitar even brandished an outlaw name equal to its beauty: the Martin OM Negative.

Clearly, Maria hadn’t purchased it for our son. But she knew exactly what this guitar would mean to me, and she knew that surprising me with the funny used-guitar-for-Isaac ruse would make me love it even more. In all its stunning physical radiance, the guitar surprised and delighted me enough.

But I felt—and still do—that the thoughtfulness behind it held even more significance. Why? Because Maria’s intuition regarding the single greatest material item I could ever hope to own was accompanied by a generosity that linked spirit to spirit. To me, it said: “I know you, and therefore I know the things you love, and I care about those things simply because you do.” For me to feel known in that way was to feel deeply loved.

Losing Touch, Gaining Touch

The Zulu greeting Sawubona means “I see you.” The traditional response, Yabo, sawubona, means “Yes, I see you, too” or “I see you seeing me.” Implicit in this greeting is the sense that until you saw me, I didn’t exist. When you stand before me, when you recognize me and acknowledge me, you bring me into being. But as we stare longer and harder into the screens of our devices rather than eyes and faces of those we encounter, we lose this sense of seeing one another.

I was having lunch at a restaurant in Portland, Oregon, not long ago, and I noticed a young woman and her child sitting at the table across from mine; the child couldn’t have been more than two years old. The woman was staring into her phone, and no matter how hard the child tried to get her attention, the woman couldn’t pull herself away. I didn’t say this, but I sure did think it: “Put your damn phone away! Your daughter just needs you to look at her!”

The child started to cry; loudly—and still, nothing.

My first instinct was to blame the woman, to brand her as a terrible parent. But knowing a bit about how smartphones are designed—not just their technical functions and features, but also the psychological design work that goes into making them nearly irresistible for anyone, even for the people who design them—I realized that what I was seeing was less about one particular mother than it was about an issue that negatively affects nearly everyone on the planet. Imagine being a child in today’s environment, where you have to compete with an electronic device for your mother’s attention.

It’s true: many of us don’t “see” each other enough. And the humanity that goes missing is making us more irritable, more isolated, and far less in touch with our sense of gratitude, the very thing known to be most responsible for our happiness.

I sometimes think of gratitude as a kind of spiritual magnet. When we focus our gratitude for a thing or an experience on a particular person, on nature, or on our conception of God, we draw that thing or experience close; we bond with it. To say that there is a mystical aspect to gratitude is not an overstatement. In terms of creating connections, there is, perhaps, nothing that compares to gratitude.

We first sense something, we have an experience, and if we desire to keep that experience alive within us, all we have to do is step up the wattage, so to speak, of our gratitude for it. Put in simpler, more logical terms: The more gratitude we have overall, the more connected we will be with the world. Conversely, when we lack gratitude for something, or when we choose not to prioritize gratitude as a part of our lives, the more removed from our own lives we will be. To activate gratitude, we need only consider the tremendous power of this “magnet.” It is always near, always available, and always ready to widen our scope of the world.

Just as apologies are only accepted as real when we, the apologizers, have taken the time to see and grasp how we’ve hurt someone, truly thanking someone means that we see and grasp the nuances of the gift we’ve received from that person. A grateful mindset shows our sensitivity to the time and effort it takes to bring a particular thing into our lives. In other words, a real thank you, real gratitude, is something of a meditation.

It requires an awareness of our love of the gift as well as the giver. Conversely, a well-given gift testifies to the time we take to know and appreciate the needs, wants, and desires of the recipient. Expert gift-givers have an openness of spirit and a willingness to put aside their own immediate needs to tune in to another person’s needs acutely. And because we continue to be amazed, not only by the gift but also by the thoughtfulness of the giver, the gratitude we feel is less likely to diminish over time. I call the diminishment gratitude burnout.

Thankfully, There’s the Thankfulness Circuit

To stay attuned to the joy of what you already have, remember this: gratitude burnout occurs because our delight with a given situation or thing fails to connect with anyone outside ourselves. We feel good when we receive things that lead to positive events, but if that joy fails to manifest itself in a close relationship with the giver, it’s as though the electrical circuit just hangs there, loose and incomplete.

But when our gratitude circles back to the giver and out to other people as well, the circuit connects. And through that connection, we draw on a powerful source of energy from beyond our limited selves. That connection back to a source creates and sustains what I call the thankfulness circuit.

But how does this relate to the gifts that surround us at all times? The ones we typically overlook, such as the gift of sight, of friendship, of light, of air, of memory, of creativity? Whom do we thank when we consider these? To whom do we direct our gratitude when no one person is involved? Religious people can focus their thanks on God, who, they believe, controls every aspect of the universe.

People who are less devout may maintain a belief in a type of force or higher power—an authority that puts the universe in motion but doesn’t necessarily influence each detail. Pantheists direct their thanks to the physical world itself. Atheists and agnostics possess a sense of gratitude no less strong and may project their thanks out to loved ones, friends, or the universe in a general sense.

A quotation attributed to the Radziminer Rebbe (1878–1942) poses this question: “If one who crosses the ocean and is rescued from a shipwreck gives thanks to God, should we not thank God if we cross without a mishap? If one who is cured of a dangerous illness offers praise to God, should we not praise God when God grants us health and preserves us from illness?”

The implications of the Radziminer’s questions are obvious. We should train our minds to the point where gratitude for everything becomes an unceasing, continuous behavior. Ronald Aronson, distinguished professor emeritus of the history of ideas at Wayne State University, writes about the power of gratitude and the challenge of expressing it.

Hiking through a nearby woods on a late summer day recently, I followed the turning path and suddenly saw a pristine lake, then walked down a hill to its edge as birds chirped and darted about, stopping at a clearing to register the warmth of the sun against my face. Feelings welled up: physical pleasure, delight in the sounds and sights, gladness to be out here on this day. But something else as well, curious and less distinct, a vague feeling more like gratitude than anything else but not towards any being or person I could recognize. Only half formed; this feeling didn’t fit into any easily discernible category, evading my usual lenses and language of perception. 1

No matter where we stand on the question of whom or what it is we should thank, it’s important to reinforce our sense of gratitude by directing it back to its source. This won’t be difficult for a traditionally religious person; if you’re less so, pinpointing the locus of your gratitude will nonetheless prove critical in harvesting the benefits of the thankfulness circuit.

Just as athletes build muscles and develop coordination through training, a strong, healthy sense of gratitude comes with time and practice.

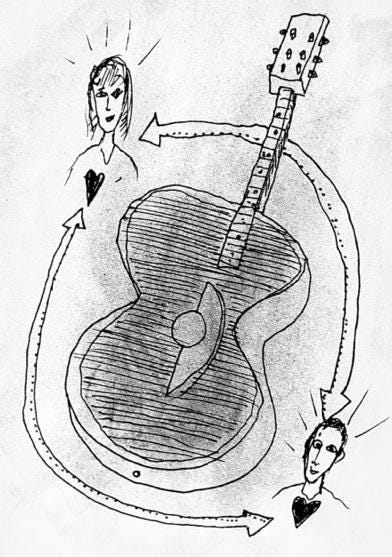

Thankfulness Circuit Sketch

Here’s a simple exercise that will allow you to strengthen your connection to your own sense of gratitude. It involves some drawing. Hey, don’t worry if you feel you’re not a “good” artist; that’s not the point here. Excuse the pun, but drawing draws on another part of the brain, and doing something a little outside your comfort zone is fun and extremely helpful—especially as we age. To begin, grab a pencil or a pen and a sheet or two of paper.

Now think of one thing you’re grateful for. This could be anything: your ability to breathe, for example, to walk from the kitchen to the living room; or just to feel the sunshine on your face. Maybe it’s a gift someone gave you: an article of clothing or a piece of jewelry. Or maybe you’re simply grateful that your older sister listened as you described a troubling problem.

Once you’ve picked that one thing, make a simple (or as elaborate as you wish) sketch that explains not only your love for the gift but also your love for the giver. In other words, the thankfulness circuit sketch originates with the gift you’re grateful for. Then it travels to the joy it brings you. And finally, it returns back to the giver of that gift. And because it’s a circle, it starts and never stops. To give you a better sense of how this works, I’ll share this example of the sketch I made when Maria gave me the Martin OM Negative. (Arrows help!)

The trick here is not to be concerned at all with whether your artwork is good. Rather, concern yourself only about whether it exists. So if you’ve chosen something not given to you by a person (say, a beautiful spring morning), then decide how to thank the nonhuman giver. Here you must, of course, capture a sense of who or what is doing the giving.

Whether you approach the question from a religious, agnostic, or atheistic angle, you will come face-to-face with gratitude in all its complexity and completeness—no small task given such an immense power. For me, this thankfulness circuit sketch reinforces a bedrock truth: the more connected I feel to the givers in my life—however, I define them—the more I feel connected to the rest of my life.

Please take a moment to let us know what you think of our work here at Beyond Belief.

Interestingly, Professor Aronson considers himself an agnostic, uncertain about the existence of God. That likely accounts for his inability to fit his sense of gratitude for a beauty-filled late summer hike into what he described as a “discernible category.”

In that case...thank you for this article😉

It seems from what you have written that it makes life a lot more straight forward to be a believing Jew who has Someone to direct our thanks to.

Interesting.

Beautiful writing and loving sentiments. One of my favorites: “I know you, and therefore I know the things you love, and I care about those things simply because you do.” For me to feel known in that way was to feel deeply loved.