The Scopes “Monkey Trial” 100th Anniversary

A Publicity Stunt that Upheld Eugenics and Put Darwin on the Defense for a Century

Image: John T. Scopes, news.uchicago.edu

This July 2025 marks the 100th anniversary of Darwin’s theory of evolution being on trial in the eyes of the American public. The story of the Scopes “Monkey Trial” is well known—how the arrest of the unassuming science teacher John T. Scopes for teaching evolution led to the “trial of the century,” where the doom of America’s soul and the fate of intellectual freedom and scientific inquiry would ultimately be decided. For a hundred years, the Scopes trial has been employed as an icon of science fighting to break free from the shackles of faith, and even today it serves as “a symbol of an ongoing struggle between conservatism and progress, religion and secularism, evidence-based science and scientific misinformation.”1

What is not widely known, however, is that the standard account of the Scopes monkey trial is largely a myth. While it is true that many progressives in the year 1925 saw religion as standing in the way of scientific, educational, and social progress, the majority of modern-day spectators forget that the notion of “evolutionary progress” in 1925 also entailed the promotion of eugenics.2 As H.G. Wells, the first scientific celebrity called on to defend Scopes, said: “the way of nature” and evolution teaches us that “it is in the sterilization of failures, and not in the selection of successes for breeding, that the possibility of an improvement of the human stock lies.”3

Indeed, the very biology textbook that the “pro-science progressives” were defending—and that the “pro-religion conservatives” were contesting—during the Monkey Trial, explicitly taught human evolutionary progress could only be achieved through the sterilization of the “evolutionary unfit” or through the removal of so-called “human parasites” from society. The social issues at hand in 1925 were thus more complex than the modern version of the myth conveys. The Scopes trial was certainly not a simplistic sparring match between evolution and the Bible. The real issue was not whether evolution was true as a scientific theory, but rather whether society should follow the eugenic promoters of “progressive science” who enlisted evolution as their main weapon in a war against the poor and the weak.

The Myth of the Monkey Trial

In a popular science series of the 1960s called The Immortals of Science, author Alice Dickinson opens her biography of Charles Darwin with an attention-grabbing account of the Scopes trial. In a poignant retelling of the Scopes Monkey Myth as it had been culturally passed down to her, Dickinson describes how “John Scopes, a young schoolteacher was being tried in a back-country courthouse” because he had “only been following the biology book provided for the Dayton schools” which “stated innocently enough that all life on earth had probably begun long ago in the ocean, in a single cell from which had developed gradually, over count-less eons, the many different living forms now scattered over the face of the globe.”

John Scopes, writes Dickinson, was well aware of “a recent state law…which had made it unlawful for a teacher in a state public school or college to teach any theory that denied the story of the divine creation of man as related in the Bible and that taught instead that man had descended from a lower order of animals…But he also knew that something far greater than his own personal misfortune was involved. That ‘something’ was the freedom of thought of an entire nation.” She details how “scientists, lawyers, and scholars had flocked to the trial, hoping to see John Scopes win,” while “on the fringes of the town a quite different sort of people—the farmers and backwoods-men of the region, carnival workers, peddlers, religious revivalists, and the followers of a score of strange religious sects—had gathered” and “prayed that young John Scopes might be convicted.”4

Dickinson explains that these backwoods Bible-believing “Fundamentalists” thought evolution was “evil” and consequently “they planned to conquer the other state legislatures one by one, and finally to aim at a federal law forbidding the teaching of evolution.” From “laws forbidding the teaching of evolution,” says Dickinson, “it was a short step indeed to laws banning the teaching of all science.” With the intent to “shackle all freedom of thought,” and “control the mind of a nation,” those who affirmed Biblical creation desired that “man’s mind be plunged back into the intellectual darkness of the Middle Ages.”

The leader of the Fundamentalists, says Dickinson, was William Jennings Bryan, a man who “had been intellectually unsuited for the job” that he had previously occupied as US Secretary of State. Bryan, she says, “was a man whose obsession was with religious beliefs of the strictest kind. He prided himself on his ignorance of science, seeing it as the arch-enemy of the religion he loved so dearly.” According to Dickinson, Bryan was Heaven-bent on “the denial of knowledge and freedom of thought,” and on “the ignoring of matters scientific.”

Facing off against Bryan was Clarence Darrow, who Dickinson describes as “the nation’s most brilliant criminal lawyer,” who “believed passionately in the freedom of men’s minds,” and who wanted to fight for scientific freedom and “focus the attention of the country on the dangers of an anti-evolution law.” As “one of the most violent of the battles over the theory of evolution,” writes Dickinson, “the trial at Dayton was the last skirmish in a battle against Charles Darwin and his ideas—a battle now admittedly won by the believers in science and evolution.”5

Where It All Started: The Drugstore Conspiracy

Image: knoxnews.com

Contrary to Dickinson’s colorful portrayal of Scopes as a beloved biology teacher who, on the basis of lofty secular principles, sacrificed himself as martyr for science and freedom of inquiry, the real Scopes was a football coach and general science teacher who never actually taught evolution, but was willing to say that he did so as part of a publicity stunt to put Dayton, Tennessee on the map. Scopes was a willing member of a conspiracy among local merchants in Dayton who hoped to sell countless malted milk drinks and other merchandise to tourists who would come to town to see the trial of a man who challenged a new state law.

This conspiracy began among a gathering of local businessmen and other prominent persons at the drug store of Fred Robinson, the chairman of the county board of education, who “presided over an emporium that sold sodas, prescriptions, and schoolbooks.”6 It all started when George Rappalyea, a local coal company manager, pointed out an ACLU advertisement in the local newspaper that offered to pay the expenses of any teacher willing to challenge the Butler Act, which forbade the teaching of any theory of human origins that ruled out Divine Creation.

The regular high school biology teacher was not interested in the proposed conspiracy, but Scopes, who had been a substitute for the biology teacher for just one day the previous year, was willing to play the part of the “sacrificial lamb.” After all, Scopes said, he had no grand plans for the summer, and he wanted to date “a blonde whose beauty and charm had caused [him] to linger in Dayton long enough to agree to the test case.”

Years later, Scopes remarked that “the blonde deserved as much credit as anyone for the trial’s being held in Dayton that summer.”7 Walter White (superintendent of Rhea County Schools) agreed to go along with the story that Scopes had taught evolution, and attorneys Herbert and Sue Hicks, both good friends of Scopes, agreed to prosecute. With everyone on board to play their parts, Rappleyea called over a nearby justice of the peace to issue a warrant for Scopes’ “arrest.” The warrant was then handed to the waiting constable—and friend of Scopes—deputy Perry Swafford, who “served” the accused. After being “served,” Scopes left the gathering for a game of tennis.

Rappleyea wired the ACLU in New York saying: “we’ve found your man,” Robinson called the Chattanooga Times and Nashville Banner to give them the news of Scope’s arrest, and White went to the local office of the Chattanooga News saluting them with the words, “Something has happened that’s going to put Dayton on the map!”8 The next day, the story appeared on the front page of the Banner, and then The Associated Press picked up the article, transmitting it to every major newspaper in the country. None of the Dayton conspirators had an intellectual interest in testing the newly passed law, and Scopes had no desire to defend Charles Darwin or the scientific theory of evolution (of which he knew relatively little). As Scopes later noted, the trial was simply “a drugstore discussion that got past control.”9

The Real Issue at Stake: The Fight for America’s Soul

Soon after the Scopes story hit the press, the situation grew well beyond the control of the local drugstore conspirators. Envisioning the upcoming trial more as a public debate about evolution than as a criminal prosecution against Scopes, the original Dayton planners and promoters of the trial invited the British evolutionist and science fiction writer H. G. Wells to present the case for evolution before the court. As Rappleyea told reporters: “I am sure that in the interest of science, Mr. Wells will consent.” Wells declined the invitation because he was not a lawyer, but he did take up “the cause of Scopes” and began to write articles and addresses against antievolutionism and against those who were prosecuting Scopes.

The case then took on a much higher level of prominence when, in mid-May, the world-famous orator, former Secretary of State, longtime leader of the Democratic Party, and the “most important evangelical politician of the 20th century,” William Jennings Bryan, volunteered his services for the prosecution. Thanks to the reporting of H.L. Mencken, Bryan is now best known as the befuddled Biblicist of Dayton, but for the thirty years before the Scopes trial, he was “the most important figure in the reform politics of America.”10

Bryan was the Democratic Party’s nominee for president in three elections, the chief campaigner responsible for the victory of President Woodrow Wilson, Wilson’s secretary of state, and for three decades the foremost champion of women’s suffrage, the federal income tax, railroad regulation, currency reform, state initiative and referendum, a Department of Labor, campaign fund disclosure, and opposition to capital punishment. Bryan’s “campaigns were the most leftist mounted by a major party’s candidate in our entire history,” and “no other populist agitator had Bryan’s impact.”11

As historian Edward Larson says of Bryan: “Probably no other American, save the authors of the Bill of Rights, could rightly claim credit for as many Constitutional amendments as the Great Commoner.”12 Bryan came to Dayton as part of a larger campaign to save America’s soul from an evil which he perceived as threatening the common men and women of America. He did not go to the Scopes trial “as a lawyer prosecuting a case before a small-town jury but as an orator promoting a cause to the entire nation.”13

H.L. Mencken, the most famous and most celebrated journalist of the day, stood diametrically opposed to the causes that Bryan championed.14 Mencken, who invented the moniker “Scopes ‘monkey trial’” and was the first to call it the “trial of the century,” had nothing but contempt for Bryan’s “common man,” referring to them as “yokels,” “morons,” “hillbillies,” and “gaping primates.” Coining the term “Bible Belt” to describe the region of America that he also called “Moron-ia,” Mencken praised “the teachings of Darwin as extended to human relations by Nietzsche.” Having heard that Bryan was going to be on the side of the prosecution, Mencken strongly urged his friend Clarence Darrow to volunteer to defend Scopes.

Darrow, America’s leading defense lawyer, was unable to resist a chance to duel with Bryan before a national audience, and he stepped forward—against the wishes of the ACLU—to represent Scopes. This was the first and only time that Darrow volunteered his services “without fees or expenses, to help the defense” of a client. Darrow was well known for his strident agnosticism, his acerbic critique of religion, and his defense of psychological determinism over and against free will. Darrow, like Bryan, held “that evolution and the Bible were not necessarily inconsistent with one another,” but he differed from Bryan in believing that “the courts should be the ultimate arbiters of what America’s public school children were taught,” and not the votes of the majority.15

He had formerly been a political backer of Bryan—supporting Bryan’s presidential campaigns in 1896 and 1900—until Bryan publicly criticized Darrow for defending teenage “thrill killers” Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb by inventing the insanity plea. Darrow’s case to the jury in the Leopold and Loeb trial was that no one could personally blame his clients if they took Nietzsche’s advice seriously when they murderously asserted their superiority over a lesser being. It was Nietzsche and society who were to blame, not his clients.

Bryan thought such a verdict was a travesty of justice because it eroded the values of individual agency and responsibility. Bringing their public feud to the Scopes trial, Darrow’s aim at Dayton was to demoralize Bryan and discredit Bible-believing fundamentalists who stood in the way of the progressive program. With the help of the sensationalist reporting of his friend, H. L. Mencken, he did just that. Darrow argued that Scopes had been “indicted for the crime of teaching the truth,” and he attributed the prosecution of Scopes to “ignorance and fanaticism [which are] ever busy and need feeding.”

The Textbook at the Center and the Devil in the Details

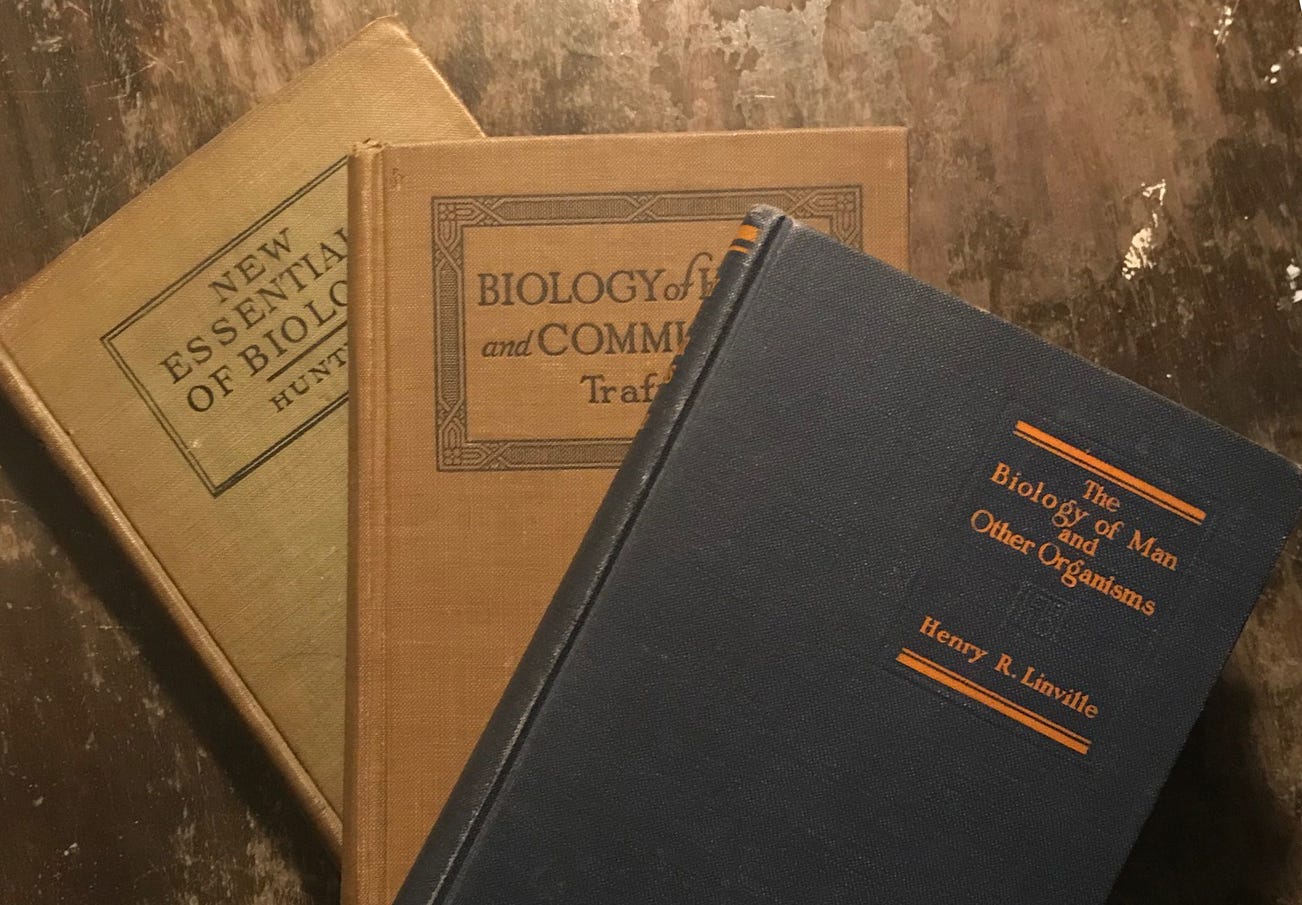

Image: the pre- and post-trial textbooks, textbookhistory.org

The textbook that Scopes had presumably taught from, A Civic Biology: Presented in Problems by George William Hunter, played a central role in the arguments at and surrounding the trial. As the state school board approved and required the biology textbook for high schools in Tennessee at the time of the Scopes trial, Hunter’s Civic Biology not only discussed evolution, which was the focus of the Butler Act, but it also advocated for eugenics. Civic Biology taught that “the health and vigor of the future generations of men and women on the earth could be improved by applying to them the laws of selection,” and contended that it is “not only unfair but criminal to hand down to posterity...the handicap of feeble-mindedness.” In a section on the application of evolution through eugenics entitled “Parasitism and Its Cost to Society,” Civic Biology discusses people groups it labels “human parasites.” The text reads:

Just as certain animals or plants become parasitic on other plants or animals, these families have become parasitic on society. They not only do harm to others by corrupting, stealing, or spreading disease, but they are actually protected and cared for by the state out of public money. …They take from society, but they give nothing in return. They are true parasites…If such people were lower animals, we would probably kill them off to prevent them from spreading. Humanity will not allow this, but we do have the remedy of separating the sexes in asylums or other places and in various ways preventing intermarriage and the possibilities of perpetuating such a low and degenerate race.16

H.L Mencken would go even further. In his book The Philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche, published a few years before the Scopes trial, Mencken argues that the Nietzschean Übermensch (“superman”) is precisely the Darwinian “fittest” who rises above the crowd of history’s rejects and weaklings. Summarizing and endorsing Nietzsche’s teaching, Mencken writes:

There must be a complete surrender to the law of natural selection—that invariable natural law which ordains that the fit shall survive and the unfit shall perish. All growth must occur at the top. The strong must grow stronger, and that they may do so, they must waste no strength in the vain task of trying to lift up the weak.17

Mencken argued that the “moral code” of Jews and Christians “was framed to protect the weak,” by weaklings who would even condemn “the quite natural act of destroying one’s enemies.” This Christian and Jewish “slave code,” as Mencken called it, must be superseded by the natural evolutionary “master code” which mandates the elevation of the fittest. “Christianity and brotherhood,” says Mencken, “were for workingmen, soldiers, servants, and yokels…for shopkeepers, cows, women, and Englishmen,” for the “submerged chandala, for the whole race of subordinates, dependents, followers. But not for the higher men, not for the superman of tomorrow.”18

The supermen and superwomen of tomorrow must claim their natural rights of superiority, and “in the future, the conventional family must yield to eugenic and rational schemes.”19 In Mencken’s work “Utopia by Sterilization,” he details a eugenic plan aimed at drastically reducing the population of the Christian “Bible Belt.” Mencken writes:

“Experts agree unanimously that it would be a good thing if we could reduce the statistical differential that now runs so heavily in favor of the unfit. If it is maintained indefinitely, there will be a wholesale degeneration of the American stock, and the average of sense and competence in the whole nation will sink to what it is now in the forlorn valleys of Appalachia.… An easy way to reduce those sorrows to-day, and almost obliterate them to- morrow, would be to sterilize large numbers of American freemen, both white and black, to the end that they could no longer beget their kind…The easy way out, and at the same time the humane way, would be to sterilize the males of the present generation, and so cut off the flow of their congenital and incurable inferiority. …Let a resolute attack be made upon the fecundity of all the males on the lowest rungs of the racial ladder, and there will be a gradual and permanent improvement.”

Even though, says Mencken, the sharecropper of “Morania may appear to the scientist to be hardly human,” the American public will still likely be blinded from the scientific and evolutionary truth by “the theological doctrine of the equality of souls before God.” Thus, “to get around this difficulty,” Mencken recommends “that candidates for the scalpel be rounded up…by posting rewards for their voluntary submission.”

Mencken’s espousal of Eugenics—which was a standard interpretation of evolution in his day—was diametrically opposed to Bryan’s populist Christian belief “that progress will come only from the moral support of the weaker.” Bryan’s objection to teaching Darwinian evolution was not so much to the scientific theory as it was to the social application of the theory to public policy. Bryan had read and understood Darwin’s Origin of Species and The Descent of Man and was able to quote from them—and frequently did so during the trial. He publicly accepted the testimony of geologists regarding the great antiquity of the Earth, believed—along with the majority of fundamentalists then—that the “days” of Genesis represented long eons of time, and even had no objection to biological evolution up to the point where God created the soul of human beings.

In his closing argument at the Scopes trial, Bryan contended that “the evolutionary hypothesis, by paralyzing the hope of reform, discourages those who labor for the improvement of man’s condition….Its only program for man is scientific breeding, a system under which a few supposedly superior intellects, self-appointed, would direct the mating and the movements of the mass of mankind—an impossible system.”

Bryan denounced eugenicists who want to make “artificial selection as efficient as the rude methods of nature” and censured “the paralyzing influence of Darwinism on the conscience…by substituting the law of the jungle for the teaching of Christ.” While “Science is a magnificent material force,” declared Bryan, “it is not a teacher of morals. It can perfect machinery, but it adds no moral restraints to protect society from the misuse of the machine.”

Bryan’s struggle was never against science, but against that which he believed was falsely called “science.” For him, the Bible was humankind’s only sure defense against the tyranny of the will to power, and the only hope for the future of both religion and science.

Erin Blakemore, “What was the Scopes Trial? How one teacher's arrest sparked a national debate,” National Geographic (June 23, 2025).

Diane Paul, “Eugenics and the Left,” Journal of the History of Ideas, 45:4 (1984); Mary Ziegler, “Eugenic Feminism: Mental Hygiene, the Women's Movement, and the Campaign for Eugenic Legal Reform, 1900-1935” Harvard Journal of Law & Gender (2008).

H. G. Wells and Francis Galton, "Eugenics: Its Definition, Scope and Aims" American Journal of Sociology, (July 1904).

Alice Dickinson, Charles Darwin and Natural Selection (The Immortals of Science), (New York: Watts, 1964).

Dickinson, Charles Darwin and Natural Selection.

Randy Moore and William McComas, The Scopes Monkey Trial (Arcadia Publishing, 2016), 6.

Moore and McComas, The Scopes Monkey Trial.

Edward J. Larson, Summer for the Gods: The Scopes Trial and America's Continuing Debate over Science and Religion (New York: Basic Books, 1997), 104.

Moore and McComas, The Scopes Monkey Trial, 9.

Garry Wills, Under God: Religion and American Politics (Simon & Schuster, 1990) 99.

Wills, 99.

Edward J. Larson, Trial and Error: The American Controversy Over Creation and Evolution, (Oxford University Press, 1985) 28.

Larson, Summer for the Gods.

Wills, Under God, 108.

Peter Cane, Carolyn Evans and Zoë Robinson, eds. Law and Religion in Theoretical and Historical Context (Cambridge University Press, 2008), 133.

George William Hunter, A Civic Biology: Presented in Problems (American Book Co, 1916), 270-271.

H. L. Mencken, The Philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche, 3rd ed. (Luce & Company: 1913), 102–3.

H. L. Mencken, ‘Mailed Fist’, Atlantic Monthly, (November 1914).

Mencken, Philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche, 186.

I had no idea this started as a publicity stunt! That a fabricated trial became projected unto the nation's collective consciousness is amazing.

I often wonder how many accepted "current events" are similarly concocted with the goal of stirring up a larger response.