Should We Forgive Evil?

Does forgiveness absolve the transgressor or the transgressed?

Image: Dr. Josef Mengele, “The Angel of Death.” fineartamerica.com

Eva Kor’s Forgiving For the Self

Ten-year-old Eva Kor and her twin Miriam were tortured at Auschwitz with other identical twins by Dr. Joseph Mengele. The twins (all children) were a close-knit group who became well-known for what they endured.

After the war, Eva and her Auschwitz survivor husband built a life together in Terre Haute, Indiana, where Eva grew into a successful real estate agent and Holocaust educator. In 2006, Eva made a documentary film: Forgiving Dr. Mengele. This was a WTF moment for me and many Jews who saw it.

Especially outraged were the other twins. How could she forgive a man who is to only be remembered as a monster? Eva said she needed to forgive him to move on, stating her forgiveness was for herself alone; she did not forgive Mengele in anybody else’s name. Not that Mengele ever sought forgiveness from Eva, the other twins, or anyone else.

Until seeing Eva’s film in 2006, I had assumed that acts of forgiveness are performances of hospitality, an other-directed action aimed at the transgressor. I always thought of forgiveness as allowing one who has wronged you to no longer have to pay off their moral debt. Judaically speaking, if a culprit repeatedly attempts to apologize, you must accept the apology no later than the transgressor’s third apology. Three times shows sincerity. The offender is now not reducible to the transgression and should not be known for it. You must both move on.

But this was not what Eva was doing at all. Her act of forgiveness in no way cleared Mengele of culpability, indeed, the act seems not to have been for Mengele at all. It was for Eva. Forgiving him helped liberate her from continuing to live as his captive. The unforgiven atrocities must be continually fought against. Eva’s apology ended her battle against someone whose death rendered the conflict otherwise unending.

The other twins understood this as a surrendering to evil. They may have remained bodily hostages of Mengele, but their fate was always to have to fight against it. Their lived experience rendered them unable to escape their embodied betrayal of having been forsaken by human civilization. Mengele held them prisoner to their dying day and they were forced to take on the responsibility of rehumanizing humanity because of the brutal way their humanity was allowed to be taken from them.

By ending her hostility to Mengele, Eva could seemingly embrace herself as fully human. But in the eyes of the other twins, this was to shirk their mutual responsibility and they thus felt betrayed. Eva absolved the unabsolvable. Their scars were no less than Mengele’s signature on their bodies and upon their souls. They could not simply walk away from it.

Eva’s film is shown in the second to last week of the semester in my ‘Ethics After the Holocaust’ class. It’s difficult to deny Eva her need to forgive Mengele to make her life more livable. The ethical question we address as a class is: in forgiving Mengele, did Eva betray her obligations and responsibilities to the other twins? It’s an intense discussion that doesn’t bring consensus. What we learn from this conversation is that forgiveness means various things to different people. Our disagreements disable us from coming to, or up, with a definitive or essential definition of forgiveness.

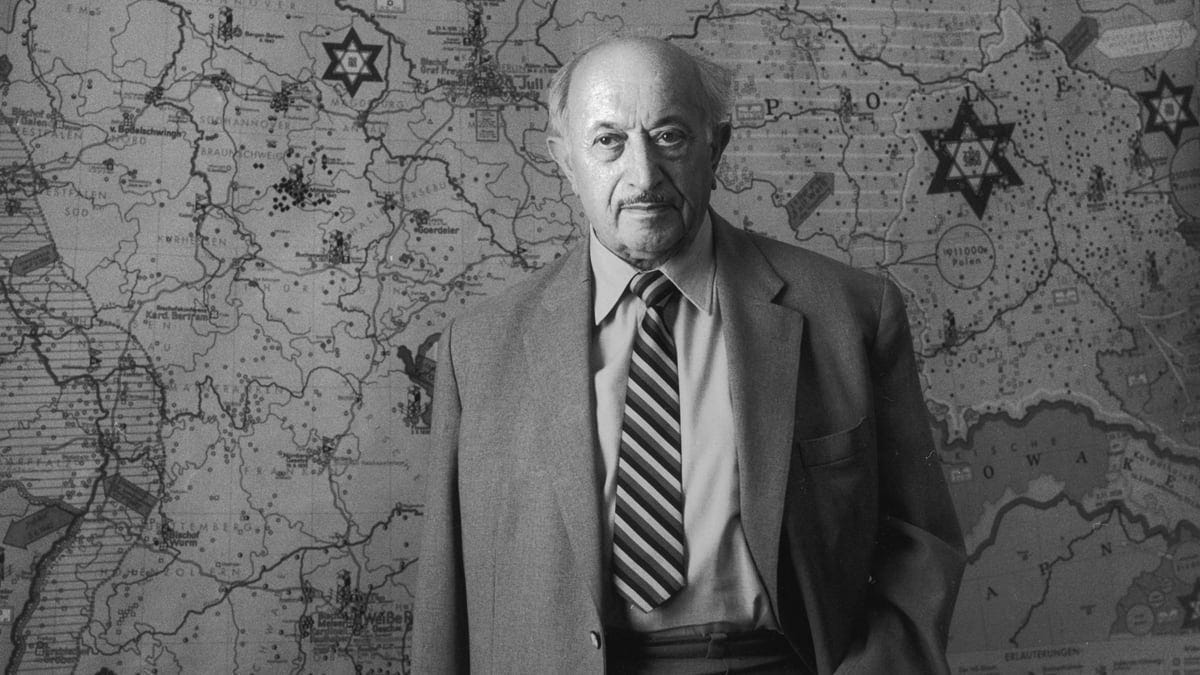

Simon Wiesenthal’s Conundrum of Forgiving for Others

Image: Simon Wiesenthal: thedailybeast.com

We spend our last week of class discussing a book by famed Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal, The Sunflower. It is a biographical account of an awful and ethically challenging moment in a murder camp. The premise suspends readers in disbelief from the first sentence to long beyond reading the last sentence.

Working with his concentration camp detail outside a hospital, a nurse surprisingly directed Simon to follow her. Would he be executed for leaving the detail? The nurse had nothing to do with him. Would he be executed for not following the attendant? These were his immediate concerns.

But he decides to follow and they walk up some stairs to a hospital room in which Karl, a young man who served in the SS, is dying. The bandages over Karl’s eyes blind him, making it impossible to see Simon, but his eyes are not needed for this moment, just his tongue and Simon’s ears.

Simon stands silently as Karl confesses his horrific crime against three hundred Jews he helped murder. Karl had taken part in locking them in a church right before setting it ablaze. As he listened, Simon moved a fly hovering near Karl’s face. He thought of Karl’s death compared to his death. Karl will have a sunflower on his grave, whereas Simon will likely not have a grave on which to put a sunflower or any marking.

Karl finished this horror confession by giving Simon his belongings, sacred possessions that were contained in a box. Karl was operating under a Christian understanding in which taking ownership of a sin and making penance allows the soul of the sinner to be cleansed. By confessing and giving his treasure to Simon, Karl was seeking absolution, the forgiveness of a Christian from a single Jew on behalf of the hundreds of Jews who could no longer forgive him.

Simon takes Karl’s box and later returns it to Karl’s parents, whom he meets after the Holocaust. He didn’t have the heart to tell them that their young son had become a murderous monster.

It turns out that Karl did not confess to every crime he committed. There were more. He confessed to this one. However, Simon had nothing to do with those in the church. Outside of being a Jew, he had no connection to them. He didn’t know them, but like them, he felt destined to be murdered. Likewise, it is hard to miss that Karl wasn’t truly concerned with his victims. For him, all Jews were the same. Any Jew would do for Karl’s confession — even if that meant risking a particular Jewish life to hear it.

When back in the camp, Simon tells his peers what happened. Like the twins and Eva, they were angry, feeling betrayed. Why didn’t Simon kill the Nazi when alone with him? Why did he listen and not leave? They asked more discrediting questions, wanting to know why Simon showed him no hostility. Was not such a stance equivalent, at least in Karl’s mind, to Simon forgiving Karl. How could he have left such an impression?

Simon concludes with a question for the reader about whether you would or would not forgive the dying man: “What would you have done in my shoes?” The student’s final class essay directs them to answer Simon’s question.

The second half of the book provides literal answers about forgiveness from notable people, from Herbert Marcuse to the Dalai Lama to former Nazi minister Albert Speer and so many more. The replies vary. Marcuse’s words on the matter chills to the bone: “I hate it when the executioner asks the executed for forgiveness.”

Forgiveness and Hospitality

Image: Eva Kor: dailymail.co.uk

Reading the replies, like the viewing of Eva’s film, again challenges our simplistic notion of forgiveness. Indeed, I ask the students if “forgiveness” is even the appropriate word. Perhaps, it is hospitality. If we substitute hospitality for forgiveness in the above examples, what changes?

Eva’s forgiveness of Mengele isn’t hospitable. Where hospitality is always other-directed, requiring an understanding of the needs of another, Eva did not aim for her forgiveness of Mengele to affect Mengele at all. She does not seek to ease Mengele’s burden, to remove his actions from his legacy. She does not wish to make her torture at his hands as if it never happened. It did happen and it should never be forgotten. Her forgiveness was self-directed, not other-directed.

Simon’s passive listening, on the other hand, did not forgive the confessing Nazi. Forgiving is active. It requires that one do something. Yet, Simon’s listening was hospitable. Judaism instructs and directs that a person cannot forgive a murderer. Only the murdered may offer forgiveness. Murder is humanly unforgivable in Judaism. Why did Simon listen?

What is clear to the students, and to me is that, at minimum, forgiveness and hospitality are not anything in themselves, but specific actions between particular people. Codependent origination; there isn’t always a universal definition between these acts or even a family resemblance between them.

For example, Eva’s forgiveness leaves little to nothing in common with a priest extending divine forgiveness to a transgressor, or a spouse forgiving their partner for infidelity. It’s the same with Simon. Fear of execution imminently informed his hospitality. Likewise, Simon’s fear did not deny he exercised hospitality to his enemy, but his hospitality takes little to nothing in common with the hospitality we associate with hosting a get-together or inviting a houseless person to eat with oneself, or the hospitality exercised in one forgiving their partner for betraying oneself.

So, what should we mean by forgiveness? Do particular circumstances demand different understandings of it? What do you mean by hospitality? Do various circumstances demand different understandings of it? While these questions may have no easy answers, the cases of Eva and Simon show us that they are questions with which we must wrestle.

Simon also didn’t offer forgiveness, that he asks us to consider it in his case is odd. He sat there and listened. Did he have any other choice? Returning the Nazi’s sacred possessions to his parents shows prizing hospitality as a condition of clemency. However, Simon didn’t absolve him. Jewish law wouldn’t approve him doing so. Judaism doesn’t allow one to forgive murder. It’s an appropriation of the murdered’s voice.

Forgiveness involves releasing the forgiven from being held hostage to an awful act. Hospitality, whether one feels it, is kindness for the other. Hospitality may be a condition of forgiveness, but it is also independent of it. This is a reason that hospitality is a necessary condition for conduct between people in the Hebrew Bible, especially for those adhering to God’s direction that we are hosts for one another. Forgiveness means no longer reducing the forgivable to their betrayal of one, to no longer treat them like a stranger. Simon and Eva misused the word. Neither of them forgave.

AMEN! Eva was simply freeing herself from living a life of victimhood; this was her victory over what Mengele did. Simon just listened. He didn't dare kill the Nazi because he would have then been slaughtered right there and then. He was kind to the parents. I was raised as a Roman Catholic but I believe in the Jewish view that certain things are indeed unforgivable. When people spout that blather about how we always have choices and we are always responsible for whatever happens to us, Mengele is the example I raise to refute that simplistic view. While Eva very likely could not really face her trauma, I kind-of sympathize with the other twins who were angry. It's possible that she was unable to be an activist whereas Simon absolutely was an activist. For me, the activist choice seems to be the correct response, but I would need to know a lot more about Eva and why she did not choose activism. It may well have been a protective form of denial to prevent herself from being overwhelmed. I admire Simon--he's one of my heroes--but I feel pity for Eva.