It's What You Didn't Say

How silence, gaps, and spaces communicate meaning.

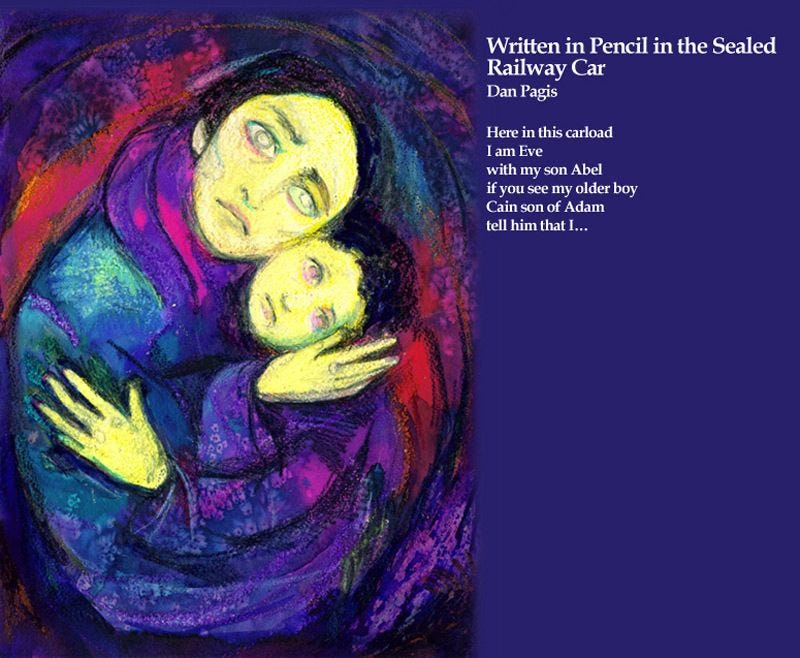

Image: pinterest.jp

I love poetry for what it doesn’t say. That might sound strange about a medium that is made up of words. But poems are also made up of spaces. And it’s the meaning in those spaces that resonate for me.

Every poem has spaces. No matter how narrative or descriptive a poem is, there is always something not being said. There is one poem in particular that powerfully exhibits how reticence, silence, gaps, spaces – however you’d like to call it – communicates meaning.

Dan Pagis, the Romanian-Israeli poet who survived a Nazi concentration camp, is most known for a compressed poem written in Hebrew (the translation below is by Stephen Mitchell).

The title, ‘Written in Pencil in a Sealed Railway Car’, is a narrative snippet. There is a sense of questions and of foreboding amidst a restrained eight-word title (four words in the original Hebrew), and the reader is gripped in a plot before the body of the poem is read. But the poem does not provide answers to the questions raised by the title.

Written in Pencil in a Sealed Railway-Car

Here in this carload

I am Eve

with Abel my son

If you see my older son

Cain son of Adam

tell him that I

The gaps in this poem are radically employed. The poem itself is condensed and even more so in the original. The pauses and silences are potent. The relationship between words and white space is tense, dynamic, transcendent, and multi-faceted. The narrative is within the words and also outside of the boundaries of the words.

The said and the unsaid in tandem offer snippets of information: there is the biblical Eve; there is a modern Eve, the fictionalized character who wrote these urgent words in pencil in a sealed railway car; there is the poet who is a Holocaust survivor (if that fact is known by the reader); and there is the ‘real’ woman, a ghost, behind this narrative which has the feel of a documentary poem. This multiplicity of speakers creates a sense of infinite possibility and an inability to grasp at any one way of reading the poem.

While we know a certain amount about the biblical Eve, we will never know more about this modern ‘Eve’. The reader senses that the narrator, the fictionalized character, wants to narrate. Not only does she begin to tell a story (her name, the names of her two sons, where she is) but she attempts to communicate something else in the final line to a reader as can be intuited from the command, ‘Tell’. What is painful here is that we are not able to receive her desire to tell, to relay a message.

The telling is not consummated. This silenced communication could have been anything: facts about where she is, a confession, life-saving information, a statement of anger or sorrow, or ‘I love him’. We’ll never know for sure what she meant to say and why she was prevented from finishing.

The reader could imagine the possibility that the speaker chose to end her words after ‘I’, no longer wishing to communicate or perhaps stopping because she was just lost in thought. The poet assumes the reader knows the biblical story of the first brothers where one kills the other. It is plausible that the mother’s speech has been cut off simply because Eve doesn’t know what she would say to her other son – his offense is too terrible. She has no words.

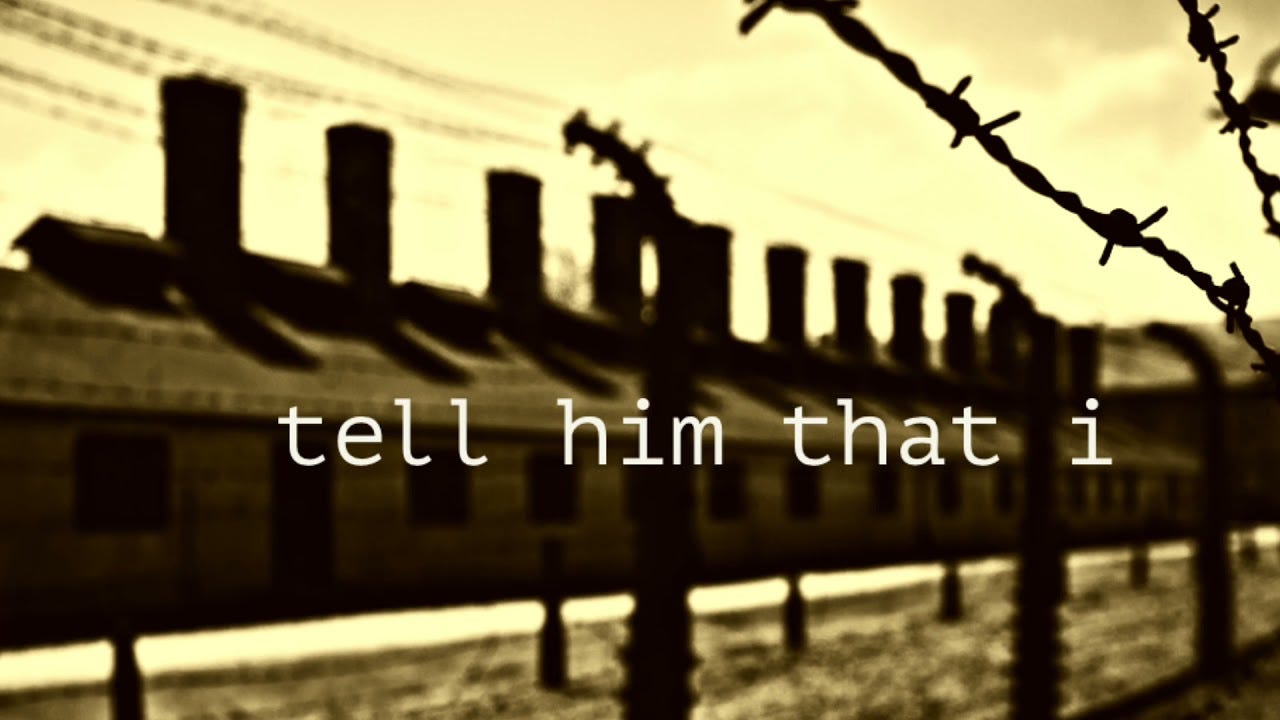

And perhaps, neither does the poet. However, the drama behind the poem and the realities of war, Jewish history, and sealed railway cars points the reader’s imagination elsewhere: the silence tells of violence. The most likely reading of the poem is that Eve was murdered and that is why she was not able to continue her message. And the fact that the biblical Eve and the modern one are fused in the poem raises questions about reincarnation and the movement of souls.

This is, however, a poem. It is not the fictionalized narrator but the poet who refuses to tell us what (fictionally) happened. Pagis does not just dramatize one story but many stories. Stories that we will never know. The white space that follows language can represent the voices of those who literally cannot speak. And the fact that the fragment has been ‘written in pencil’ highlights that even this person’s partial story can be easily erased.

When we are presented with a poem such as Pagis’s that brings the reader to the edge of an abyss, we have to accept that we will never know the details of that abyss. The gaps in narrative suggest that there are an infinite number of narratives, past, present, and future.

Every poem has narrative gaps. No poem can tell everything that happened. Some poems call attention to those gaps and others do not. However, in all cases, to put it in Levinasian terms, just as ‘the face’, as he calls it, or the ‘Other’, is not reducible to complete comprehension or appropriation, neither is a poem. The ‘Other’ is greeted or received without becoming fully known.

Image: youtube.com

The following riddle (originally in Yiddish) is ascribed to the nineteenth-century Polish rabbi Menachem Mendel Morgensztern, better known as ‘the Kotzker Rebbe’: ‘If I am I because I am I, and you are you because you are you, then I am I and you are you. But if I am I because you are you and you are you because I am I, then I am not I and you are not you!’ The riddle is a comic yet gravely serious warning to the ‘I’ against merging with the other, against inserting the narrative of the ‘I’ onto the other’s narrative. The rabbi’s saying encourages an acceptance of a separate perhaps never to be fully known ‘you’ and implies that doing so allows both the ‘I’ and the ‘you’ to thrive.

This approach to relationships can be applied to the reading of a poem – it is important to resist full comprehension. John Keats wrote that ‘I am certain of nothing but the holiness of the heart’s affections and the truth of imagination’. Silences allow readers to follow Keats’s example and be certain of nothing but what they love and what they imagine, phenomena that occur within the self.

Knowledge is incomplete. Only the divine knows everything; we are just given snippets of the ‘truth’. This fact is reflected in poetry which is filled with silences. An awareness of this aspect of poetry helps readers understand something about the nature of life: we are surrounded by fragments, by shards of meaning. The spaces around those shards are rich with truths we can sense but will never fully comprehend.

Although we can never completely understand another person, when we realize that life is full of ellipses, it invites an opportunity to not only accept mystery but also to respond to those gaps, either through imagination about expanded possibilities and outcomes not yet in evidence, or through action that fulfills responsibilities or creative impulses that would otherwise go unrealized. We can become more fully realized agents in the world, granting ourselves a more explicit and engaged role in the lives of others and in our own.

Indeed, the end of the poem is very evocative. It invites the imagination to empathize and to fill the gap. No one can be omniscient; there is always more, expanding into infinite space.

I love this, thank you. It struck me that for the narrator to be with her deceased son Abel, she herself must be dead in some sense. Additionally, in the original Hebrew, the last line can also be read as a complete sentence: "Tell him that I am." It deepens the ambiguity beautifully. The poem can be read both as a mother reaching out to her wayward son, and a voice from beyond, reminding history's first murderer of the soul's eternal life.