Göbekli Tepe: The Sanctuary Before Civilization

A Discovery that Reshaped History

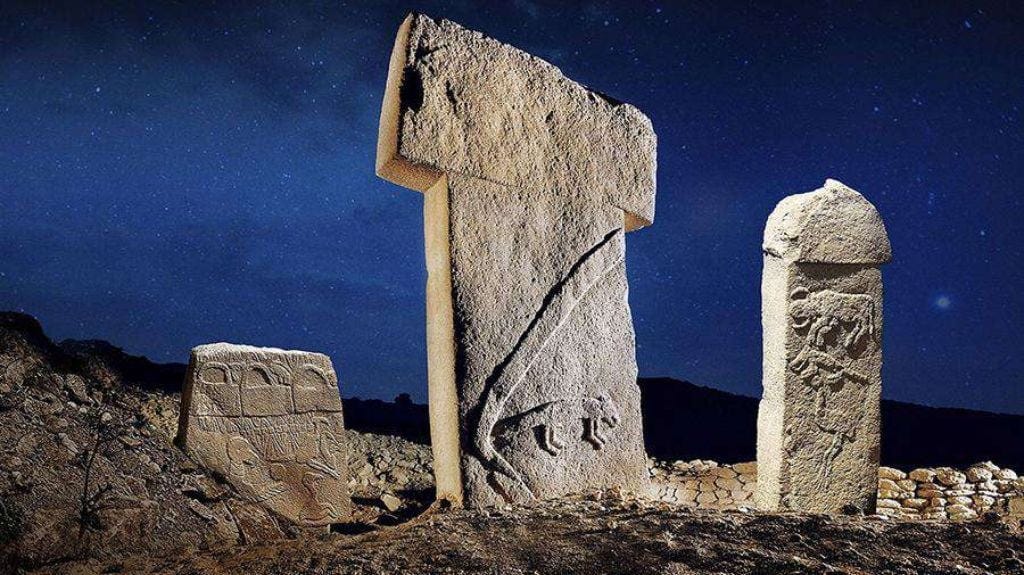

Image: Göbekli Tepe, heytripster.com

Lying tranquilly beneath the earth for over twelve thousand years, the archeological site Göbekli Tepe bears witness to a mysterious human past that has long been forgotten by time. A lost sanctuary of unknown scale that is shrouded in mystery, its massive monuments silently speak to us through a sacred symbolism that still awaits deciphering. Positioned between the upper reaches of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, Göbekli Tepe is the world’s most ancient monumental structure, being over six thousand years older than Stonehenge and eight millennia earlier than the Egyptian pyramids of Giza. But while displaying a degree of technological sophistication that was millennia ahead of its time, the monument was constructed and occupied by pre-agricultural peoples who were largely nomadic.

The World’s First Temple

Göbekli Tepe was first noted as a place of possible archeological interest during a 1963 survey. German archaeologist Klaus Schmidt then recognized the site’s potentially revolutionary importance and began archeological excavations there in 1994. Featuring numerous circular and rectangular enclosures containing massive, T-shaped limestone pillars (with some of them weighing up to 50 tons), the archaeology of the site revealed no evidence of permanent human habitation, no signs of houses, no hearths, no domestic tools, and no graves. While the precise purpose of Göbekli Tepe is still unknown, the monumental architecture and the intricate carvings of wild animals like foxes, lions, boars, vultures, and snakes—with super massive humanoid figures at the center—suggested to Schmidt and others that it was some type of temple or sacred gathering place for ritualistic and ceremonial activities.

Current researchers believe that fellowship and feasting were a major part of the sacred ceremonial gatherings at the site. The evidence is clear that strong drink was overflowing there, as archaeological excavations unearthed large stone troughs—holding up to 42 gallons—with traces of oxalates indicating beer for communal consumption.1 Food at Göbekli Tepe was likewise plentiful, as researchers have found tens of thousands of processed wild animal bones, suggesting large-scale hunting ventures and the subsequent consumption of game animals such as gazelle, red deer, duck, and aurochs.

The sculptures and reliefs at the site substantiate this view of Göbekli Tepe as a type of temple where feasting was prominent, in that they show various animals in scenes related to food preparation and possibly ritual sacrifice. In addition to the zoological iconography of the site, which invokes a vision of the central humanoid figures surrounded by myriads of animals, the design of the structures—with 12 massive pillars astronomically oriented encircling 2 massive central pillars—suggests that the site was also used for marking the equinoxes, observing the solstices, and for charting the stars.

A Discovery that Reshaped History

Before the excavation of Göbekli Tepe, scholars had long thought that the human discovery of agriculture was the primary factor that first gave rise to our capacity for complex social organization and massive-scale building ventures. Now, though, it is clear that long before the advent of agriculture, hunter-gatherer societies were capable of sophisticated planning, advanced geometric understanding, deeply symbolic spiritual expression, and the ability to organize a large labor force for the purpose of constructing monumental projects.

In light of Göbekli Tepe, many researchers now believe that the desire to worship and connect with the Divine, together with feasting and fellowship, were the primary motivations for ancient people to first come together in large groups to build monumental structures. As Schmidt reflects: “Gobekli Tepe upends our view of human history…We always thought that agriculture came first, then civilization: farming, pottery, and social hierarchies. But here it is reversed, it seems the ritual center came first, then when enough hunter-gathering people collected to worship…they realized they had to feed people. Which means farming.”2

Ancient Astronomers

Image: publicacionesherbertore.blogspot.com

As researchers began to study the geographical orientation of the monuments at Göbekli Tepe and analyzed the details of the carvings, they observed how the pillars aligned with celestial phenomena as they would have occurred around 12,000 years ago. One enclosure at the site seems to be oriented towards the rising point of the Sun on the day which marks the end of solar summer and the beginning of shorter days—the halfway point between the summer solstice and the autumn equinox.

A second enclosure “shows an orientation towards the rising point of the Moon at its minor standstill.”3 Other structures appear to “have been oriented—or even originally constructed—to celebrate and successively follow the appearance of a new, extremely brilliant star in the southern skies: Sirius.”4 Researchers have also pointed out carvings that appear to track the days of the year, adding up to a solar calendar of 365 days (consisting of 12 lunar months plus 11 extra days). Depicting the cycles of both the Sun and the Moon, such carvings could represent the first ever solar calendar—predating all other known calendars by many millennia.

The Göbekli Tepe site may also have been created to serve as a time capsule to mark—and tell future humans about—a decisive celestial event that changed the way of life of the people who made the monument. Some scholars believe that the ancient architects and artists of Göbekli Tepe created some of the central reliefs to record the event of a comet smashing into the earth around 12,850 years ago during what is known as the Younger Dryas period.

This comet impact ushered in a mini ice age that lasted over 1,200 years, wiped out many species of large animals, and altered the way that the humans at that time produced food—perhaps even motivating them to develop agriculture to cope with the cold climate and loss of big game.5 During his initial excavations, Schmidt noted that the material which filled the site did not show the uniform horizontal stratification of natural deposition but rather was indicative of deliberate, bulk-filling activities. Since the site appears to have been intentionally buried after over fifteen hundred years of use, many researchers believe that those who backfilled it with tons of earth and gravel were preserving it for future generations to find.

Was Our First Written Word “God”?

Disclosing what may well have been the first spiritual sanctuary and celestial observatory in the world, Göbekli Tepe’s carvings may also reveal the beginning of humanity’s endeavor to symbolically describe the Divine. On the ancient 15-ton single-stone columns at the center of the enclosures, a symbol looking like an “H” bracketed by two semi-circles is solemnly inscribed. Scholars have pointed out that this central symbol on the columns is identical to a character that appears as a logogram in the now extinct hieroglyphic language of the Bronze Age Luwians of Anatolia.

Among the Luwians, who lived in the geographic region of Göbekli Tepe millennia after it was buried, this same exact symbol represented the word for “God”. Because “Luwian is one of the oldest, if not the oldest known Indo-European languages, and a likely descendant of the hypothetical Proto-Indo-European (PIE) common ancestor of all members of this language family,” some scholars believe that there could be a continuity of symbolism between the Luwians and the people who created Göbekli Tepe. If that is indeed the case, then our species’ very first written word was “God.”6

Oliver Dietrich and Laura Dietrich, “Rituals and feasting as incentives for cooperative action at early Neolithic Göbekli Tepe,” in Kimberley Hockings and Robin Dunbar, Alcohol and Humans: A Long and Social Affair (Oxford University Press, 2020).

Klaus Schmidt quoted in Sean Thomas, “Is an unknown, extraordinarily ancient civilisation buried under eastern Turkey?” The Spectator (May 2022).

Alessandro De Lorenzis and Vincenzo Orofino, “New Possible Astronomic Alignments at the Megalithic Site of Göbekli Tepe, Turkey” Archaeological Discovery, Vol.3 No.1, (January 2015)

Giulio Magli, “Sirius and the project of the megalithic enclosures at Gobekli Tepe” Nexus Network Journal 18, 337–346 (2016).

M. B. Sweatman, “Representations of calendars and time at Göbekli Tepe and Karahan Tepe support an astronomical interpretation of their symbolism,” Time and Mind, (2024) 1–57.

Manu Seyfzadeh and Robert Schoch “World’s First Known Written Word at Göbekli Tepe on T-Shaped Pillar 18 Means God” Archaeological Discovery 7, (2019), 31-53.

Hello there Joshua, we look to have similar interests, so I thought I’d say hi; I’ve not been on here long.

I write about historical curiosity’s, through a philosophical lens.

I thought you may enjoy my latest piece on Giants:

https://open.substack.com/pub/jordannuttall/p/giants-in-newspapers?r=4f55i2&utm_medium=ios