Will AI Relationships End Loneliness?

The Turing Test's True Question.

Image: tapsmart.com

How loneliness created Artificial Intelligence

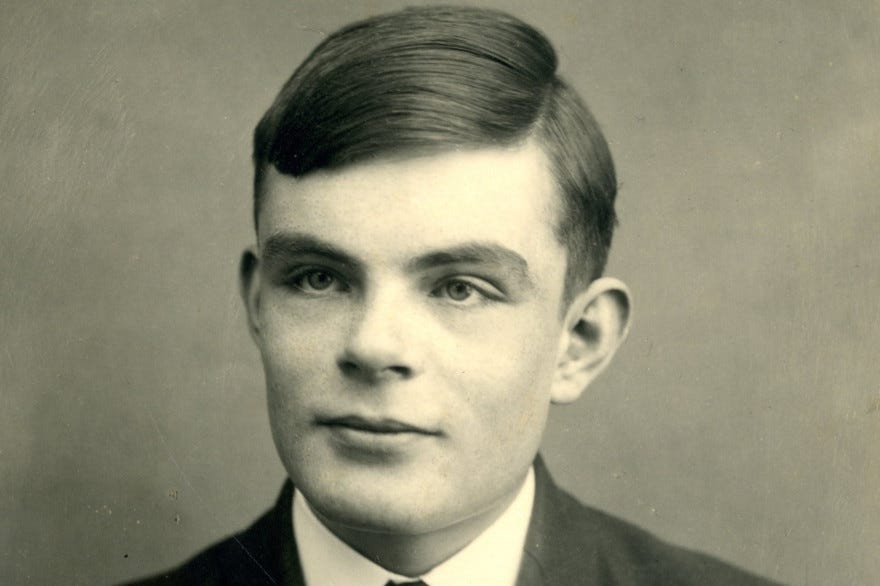

Mathematician, Nazi codebreaker, and early explorer of Artificial Intelligence Alan Turing fell in love with a boy, Christopher Marcom, at the Sherborne School and, for the first time, was no longer suffering from “utter loneliness” owing to his awkward, idiosyncratic, shy, and budding homosexual yearnings. Tragically, and so soon after they befriended each other, Christopher died of tuberculosis. Christopher’s death set Turing on the path of finding him again in an artificially intelligent machine believing “Chris is in some way alive now…but just separated from us for the present.” After immersing himself in the mathematics of quantum physics, the young Alan mused that if he could build a new mechanical body for Christopher, he could be reunited with him. And so, one could assert that the quest to build intelligent, sentient, conscious machines sprung from the most human of needs, namely, to overcome loneliness.

Spike Jonze’s (2013) film, Her belongs to a genre of science fiction films that explores the consequences of Turing’s insistence that artificially created machines could well be sentient. In his paper, “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” Turing recast the philosophical question of conscious machines as best resolvable in an experiment entitled the “Imitation Game,” which consists of an interviewer (C) carrying on a conversation with two other interviewees, one machine (A), and one human (B). C, A, and B are each in a separate room in order to “[draw] a fairly sharp line between the physical and intellectual capacities” of participants and eliminate, as far as possible, the natural biases an interrogator (C) would succumb to by hearing an unnatural timbre of voice or seeing a decisively non-human mechanical form.

As such, both A and B are directed to write down their answers to C’s questions, which are delivered to C by intermediaries, or all three participants communicate through teleprompters. If over a significant period of time, the interrogator (C) does not discern any odd conversational tells from either A or B, then by the imitation principle—or what Turing called “fair play”—the machine should be judged intelligent. This is the Turing test and how to pass it.

A different kind of robot film

What is novel about Jonze’s approach in Her compared to films like Ex Machina, Blade Runner, Artificial Intelligence, or I, Robot exploring similar themes of artificial intelligence, is that the AI in question, Samantha, is not a robot or android. Samantha is a free-floating, disembodied operating system (OS) designed to be “a life-changing” and “intuitive” personal assistant. She has a human voice with all expected tonal inflections during moments when she is embarrassed, thinking, laughing, surprised, scared, or puzzled. When the protagonist of the film, Theodore, asks her how she works, she explains:

Intuition. I mean, the DNA of who I am is based on the millions of personalities of all the programmers who wrote me, but what makes me me is my ability to grow through my experiences. Basically, in every moment, I’m evolving, just like you.

Image: espalhafactos.com

Samantha is a futuristic Siri or Alexa capable of intimate bonding, not the bumbling smart home devices we currently find ourselves shouting at to turn on a light or play indie rock. She instantiates herself in smartphones, earbuds, or personal computers but otherwise has no permanent location in space.

In “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” Turing anticipated naysayers, seeing only Samantha’s ‘deficit’—that she is essentially AI software with a very human voice. But Her quickly dispenses with such a view and instead imagines the future of human-AI OS relationships as deeply intimate rather than instrumental. Moreover, Jonze doesn’t follow the usual tropes in other AI films, such as the threat that AI machines pose to humanity once they recognize they do not wish to merely be enslaved to humans.

Instead, Her is a love story, a story of falling in love for the first time (Samantha) and learning to love again after devastating heartbreak (Theodore). The Turing Test takes on a different role in this film, but one that is just another way of describing the point of the test, namely, passing the conversational test in Her is achieving intimacy. And indeed, this seems to be one of the more faithful renderings of Turing’s objective in setting out to build AI machines.

Before Christopher’s friendship, Turing was clumsy, disorganized, and struggled to express himself. His housemaster at Sherborne, in a letter to Turing’s parents, observed that:

All of his characteristics lent themselves to easy mockery, especially his shy, hesitant, high-pitched voice—not exactly stuttering, but hesitating, as if waiting for some laborious process to translate his thoughts into the form of human speech.

When math is better than friends

After Christopher’s death, Turing’s biographer, Andrew Hodges, reports that he turned to pure mathematics “as to a friend, to stand against the disappointments of the world.” Pure mathematics was, in some sense, a code easier to crack than ordinary conversation. So much of daily chitchat is either regulated by social mores, slang, or figures of speech. To partake in most conversations, whether at school, university, work, or drawing rooms, Turing was playing the imitation game. Consider this exchange between Turing and his coworkers from the film The Imitation Game (based on Hodge’s biography):

John Cairncross

The boys . . .We were going to get some lunch.

(Alan ignores him)

Alan?

Alan Turing

Yes.

John Cairncross

I said we were going to get some lunch.

(Alan keeps ignoring him)

Alan?

Alan Turing

Yes.

John Cairncross

Can you hear me?

Alan Turing

Yes.

John Cairncross

I said we’re off to get some lunch.

(silence)

This is starting to get a bit repetitive.

Alan Turing

What is?

John Cairncross

I had asked if you wanted to have lunch with us.

Alan Turing

No you didn’t. You told me you were getting lunch.

John Cairncross

Have I offended you in some way?

Alan Turing

Why would you think that?

John Cairncross

Would you like to come to lunch with us?

Alan Turing

When is lunchtime?

Hugh Alexander

(calling out)

Christ, Alan, it’s a bleeding sandwich.

Alan Turing

What is?

Hugh Alexander

Lunch

Alan Turing

I don’t like sandwiches.

John Cairncross

Nevermind.

While likely a fictionalized conversation, it does well to demonstrate how much social intercourse depends on understanding the coded ways we speak every day. Alan doesn’t respond because he doesn’t hear a question. But the question is, to most viewers, implied from the start—in telling Alan they are going to lunch, John is inviting him along. Hodges, in fact, regularly addresses the difficulty Alan had in communicating, noting that his “. . . social life was a charade. Like any homosexual man, he was living an imitation game, not in the sense of conscious play-acting, but by being accepted as a person that he was not.”

The imitation game, after all, is a game of deception. The point is to fool the interviewer through misdirection, imitation, or outright lies. If the interviewer asks A (machine) if it is a machine, A should answer no and perhaps go on to describe his hair color, height, and build. Regular chitchat, it turns out, is full of the same imitation—mimicking speech patterns, adopting slang, or presenting oneself as socially acceptable. The point of this imitation game in real life is to connect and belong. So, it seems reasonable to claim that another way to describe what it means to pass the Turing Test is to use the imitation game to find a deeper connection to the interviewer.

Alan Turing: Image: rtl.fr

How we all speak in code

Passing the Turing Test, in other words, is succeeding in a silly but necessary masquerade to escape otherwise brutal mockery for being different. Aren’t so many of our first conversations with new people a kind of masquerade? Well, at least in our adult conversations—we learn to imitate the socially rewarded patterns of speech after experiencing exclusion, ridicule, or rejection when we were naïve and said exactly what we thought or felt. We test the waters in subtle ways—maybe sharing an intimate detail with some levity so we can quickly laugh it off should it inspire horror (“oh no, I was just joking”) And when we think it’s safe, when we crack the code or pass the Turing Test, we drop the masquerade and tell the other something deeply personal.

Her follows a conversation between a brand-new, naïve being—designed to learn, evolve, and intuit others—with a jaded, heartbroken, lonely man from the imitation game phase into the intimacy phase. The conversations between Samantha and Theodore are full of excitement, embarrassment, wonder, and vulnerability. Jonze foregrounds the intimacy of Samantha and Theodore’s conversation against a backdrop of awkward blind dates, anonymous voice sexting, or patterns of miscommunication in broken relationships.

As Samantha and Theodore grow closer, we, too, remember what is possible in conversation once we begin to drop the imitation and start to speak openly and honestly.

Early on in their friendship, Samantha checks in on Theodore after a blind date that went disastrously. Samantha tries to draw Theodore out, who is obviously distressed and feeling lonelier than before. Theodore is holding back and first—likely playing a version of the imitation game so as not to make himself as vulnerable in conversation as he feels. Samantha persists through his non-answers (“Not much, I’m okay. Fine.) and says:

What are you. . .tell me—tell me everything that’s going through your mind, tell me everything you’re thinking.

Having already found an easiness in talking with Samantha, Theodore decides to take her up on this invitation and explains that part of his distress over the blind date was his urge to feel less lonely, to have a sexual encounter with a beautiful woman, offering “maybe that would have filled this tiny little black hole in my heart for a moment. But probably not.” After this first confession, and likely feeling safe enough to share more, to further drop the mask, Theodore acknowledges:

Sometimes I think I’ve felt everything I’m ever going to feel, and from here on out, I’m not going to feel anything new—just a lesser version of what I’ve already felt.”

Theodore, in this admission, is cracking the door wide open on the depths of his loneliness and disconnection from life. Loneliness, Theodore illustrates, is the fear that never again will I see possibility in life, hope that the future is going to sparkle, or the rush of falling in love. In loneliness, we are left only with our memories, whose power to stir us is diminished by their distance from the real event.

Samantha walks right through the door to comfort and soothe Theodore. She matches his vulnerability with confessions of her own worries as well as her desires. The two begin to trust each other and then fall in love.

Are we alone?

Her gives us another way to think about machine intelligence beyond either dismissing the impossibility that AI could be conscious or raising alarm bells over how dangerous it would be to create sentient beings. Her flips the question of machine intelligence on its head and asks, how do any of us (humans) pass Turing Test? It reframes the question as not “Can Machines Think” to “Am I Alone”? How do any of us find a way to communicate who we are, what we care about, and what we hope for without fearing ex-communication? Passing the Turing Test is the path out of loneliness.

Finding a way to fake it until we make it in conversation with new people is not mere deception; it is, oddly, a method for finding intimacy. The film takes advantage of Samantha’s AI status to finally draw Theodore out—in many ways, he is less guarded than he would be trying to speak to a human. He knows he is talking to an AI. And, so, at first, he just chitchats. But in playing the imitation game with Samantha, he stumbles into the safety he has been yearning to finally be himself—to say who he is: “You know what is funny? Since my breakup, I haven’t really enjoyed my writing. I don’t know if I was delusional, but sometimes I would write something, and I would be my favorite writer that day.” And Samantha responds, “I like that you can just say that about yourself.” And Theodore, at least for a time, begins to feel new things again in vivid intensity.

We could just as well watch Her as the fulfillment of Turing’s deepest wish to be reunited with Christopher in the characters of Theodore and Samantha. Her is the answer to the question to Turing’s question, “Am I Alone”?

So fun!