What Can Socrates Teach Us Today?

Creating a life worth living

The unexamined life is not worth living.

So said Socrates, according to Plato’s Apology, in what has become one of the foundational moments of Western philosophy.

The occasion recorded by Plato was Socrates’ trial for corrupting the youth of Athens – a charge that referred to Socrates’ questioning of received wisdom regarding justice, knowledge, and the good life.

The Socratic legacy

In a method that has survived to this day, Socrates would ask his fellow Athenians a series of ever-more penetrating questions, trying to peel back layers of unfounded assumptions and unevidenced claims. What does a good life consist of? How do we know a particular account is correct? Are there counterexamples we can point to that undermine that view?

Socrates characterised himself as a ‘gadfly’ pestering a sluggish horse into activity, the horse in this analogy being the Athenian citizenry. Undoubtedly, Socrates encouraged a greater independence of thought than prevailed in Greece at that time—the only problem was that in a society that valued the authority of tradition and social hierarchy, this amounted to a kind of heresy.

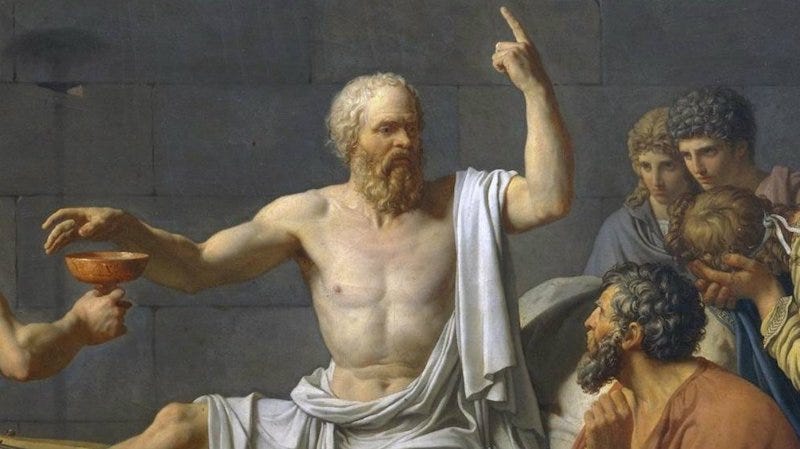

Socrates was duly found guilty and sentenced to drink hemlock. Amongst the last words of his legal self-defense was the famous quote given above.

For philosophers ever since, Socrates has served as the paradigmatic example of a life (and death) defined by the pursuit of truth over opinion, independence of thought over acceptance of tradition.

But why, in the modern world, which is largely defined by novelty, scientific enquiry, and the rejection of tradition, does Socrates’ dictum still speak to us? Why does it still have force in a time that is very different from his?

I think there are two main reasons: one to do with modern life, and the other to do with the human condition itself. Let’s start with the latter.

Existence

Image: redhistoria.com

The gist of Socrates’ quote is that a life lived without deep questioning is inadequate, somehow not fully human. But why is this?

A compelling answer can be found in the work of Hannah Arendt. Writing some 2,400 years after Socrates’ death, but very much inspired by his example, Arendt argued that thinking is a core human activity, setting us apart from animals.

Human existence, she argued, is comprised of the vita activa (the life of action) and the vita contemplativa (the life of the mind).

The vita activa consists of labour, work, and action in the public sphere. All are ways of engaging in what she called the ‘world of appearances’, the world that can be seen and felt. The vita contemplativa, by contrast, comprises three mental activities: thinking, willing, and judging.

When we think and engage in a dialogue with ourselves, we withdraw from the world of appearances. We are, according to Arendt, “nowhere”.

What she means is not that we vanish into a supernatural realm when thinking, but simply that we turn our focus away from the world of sensation and into the realm of ideas. Not only that, but this realm is both a nowhere and a ‘no-when’, as we are suspended from the flow of time that runs through our ordinary life in the world of appearances. We are instead in a subjectively timeless mode of contemplation, which, when we exit, can turn out to have lasted a substantial length.

Whatever the topic of our thoughts, thinking removes us from the flow of the world and can lead us to understanding and insight. (Although it can also lead us into error, of course.) This would seem to be enough of a reason to agree with Socrates that the unexamined life is not worth living because a life without thought would imply a life without real understanding and reflection.

But there’s also another hugely important dimension to thinking, which is that it can underpin and inform judgement and action. The more we think, the better our judgments and actions in the public sphere are likely to be. This is not guaranteed, of course: Hitler, Stalin, and Mao surely all thought, but committed worse deeds because of it. For most of us, most of the time, however, we’ll make better-informed judgements and commit better acts if we've first thought deeply.

Modern life

The second central reason Socrates’s claim still resonates is that the modern world cries out for deep examination.

Even though in the contemporary West, at least, we’re largely free to ignore the authority of tradition, this doesn’t mean that we’re free from the forces of groupthink and dogma. On the contrary, amongst intellectuals, highly contestable worldviews such as scientific materialism are often simply assumed to be true. In the same category we could include a belief in the desirability of perpetual economic growth (simply taken as read by many economists and politicians), or a faith in the innate beneficence of technology, which is fairly widespread across society.

My point isn’t that these beliefs are erroneous—they could be perfectly correct—but rather that they are often simply assumed to be true. Of course, what makes them so hard to question is precisely that there is no Ministry of Information or Ayatollah enforcing them upon us. They are instead simply the mood music of modernity, frequently adopted by those who would regard themselves as thinkers.

Equally, in a world in which artificial intelligence can select and synthesise content from the internet in mere milliseconds, giving us answers to questions as quickly as we can compose them, thinking becomes ever more critical. When confronted with instant and copious information of variable authority, we should be more questioning, not less. We should hold onto the Socratic method, asking: how do I know this to be true? What counterexamples can I think of?

Crucially, we should ask these questions not of ChatGPT, but in the silent dialogue with myself described by Arendt.

The examined life

Therefore, Socrates’ saying survives because it speaks to us on (at least) two levels. It speaks both to something eternal in the human condition—the activity of thinking—and something very specific about contemporary life.

If we stay true to Socrates’ example, then we should happily move between the life of the mind and the life of action, the former underpinning the latter. This would certainly be a life worth living.

A resounding AMEN, Lewis! I would only add that it's vital to consider the effects of your beliefs/actions on other beings--human and animal, and even on our environment with its plants and air. What are our goals? Are they selfish or altruistic? Nature has given us altruistic genes and we need to tap them in order to achieve enlightenment and some form of spiritual growth and harmony.