The Titan Implosion and the Human Condition

On the good and evil of the "limit experience."

Comedian Demetri Martin said, “I used to take part in sports a lot, but then I realized you can just buy trophies. Now, I’m good at everything.” It’s funny because we understand that buying a trophy makes it seem that you earned an award without putting in the work. Tragically, that same logic led to the unnecessary deaths of five people, including a father and son, on the imploding Ocean Gate submersible Titan attempting to visit the wreckage of the Titanic.

The Human Predicament

Jean-Paul Sartre famously asserted that humans are condemned to freedom. His childhood friend and lesser-known fellow founder of existentialism, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, disagreed, countering that we are condemned to a search for meaning. The human condition, Merleau-Ponty argued, is to have a hole in your soul, to be a being in search of meaning in a universe that provides only facts.

Please take a moment to let us know what you think of our work here at Beyond Belief.

Turning facts into meaning is hard. Trust us, as professional philosophers, that’s what we do for a living. It demands thinking deeply about things usually dismissed as trivial. Philosophers are often accused of “navel-gazing” because we give more than passing attention to what seems to be mundane. “You are overthinking it,” is a common accusation, “making a mountain out of a molehill.” But that is what making meaning requires, moving beyond the surface, plumbing the depths of the normal to see unexpected beauty, or ignored immorality, or surprising interconnection we would not have otherwise noticed.

It sometimes requires adopting a perspective removing us from the center of the universe, admitting that ours is not the only viewpoint of value. It means focusing on the experiences of others, sometimes painful experiences we might have caused or at least benefitted from, showing that we are not the hero of every story. Indeed, it means realizing that sometimes we are the villains. It is heavy work that can be boring or depressing some of the time.

Until it isn’t. When you have an insight, when you come to understand something you previously merely knew, the feeling is transcendent. There is a sensation of being unified with Being itself. You experience a Gestalt switch, like seeing a rabbit as a duck and a duck as a rabbit. The world becomes more multifaceted, profound, and interwoven in designs that appear for the first time. A curtain pulls back, exposing the wonder it had been obscuring. It is a feeling you never forget.

As teachers, we see it in the faces of our students when they get it. We’ve been saying the same thing in seven different ways, but for some unknown reason, this time, it clicks. The student’s face lights up, eyes grow wide, and mouth opens in a half smile. You can see the mind in overdrive as it searches to make different connections with the new dot it now possesses, seeing how this realization forces the re-understanding of other things already understood. The scaffolding is enlarged. The web is growing. That is the moment that makes a teacher a teacher. That is why we do what we do. It is rewarding beyond words. That is the moment of being human, of filling in—even just a little bit—the hole in your soul.

Stealing the Trophy

But it takes getting grease under your cognitive fingernails, working up an intellectual sweat, sometimes even pulling a mental muscle. Who wants that? Wouldn’t it be cool if you could just wallpaper over the hole, pretending it is no longer there? Isn’t there a shortcut that eliminates the discomfort and work?

There is…sort of. It depends upon what we consider important: meaning or the exhilaration of finding it, playing the game, or receiving the trophy.

Because we are neurologically rewarded with pleasure for finding meaning, we can convince ourselves that anything that feels good is thereby meaningful. So, we try to fill the hole with superficial elements—glory, fame, wealth, sex, food—Anything to avoid the challenge of making meaning.

Of course, these can be used authentically. One could find profound meaning in cooking delicious dishes for people you love, feeding the homeless, delivering for Meals on Wheels, or changing your diet to use ingredients farmed in a way that helps heal the earth. All of these use food as the fulcrum point for a lever that elevates us by understanding and meeting the needs beyond our own, making our lives meaningful.

But that is not what we do most of the time. Instead, we use food or sex or other desirable things as part of what Aristotle termed “a life for cattle,” seeking mere surface pleasure, hoping it will cover over the hole we are avoiding filling.

This is most effective if the resulting euphoria is overwhelming. Drugs like cocaine and heroin make us feel better than we could possibly feel by releasing torrents of the very same neurotransmitters that we earn drips of when we find meaning. In using them, we think we are getting a bigger trophy without getting our uniform dirty.

A similar mechanism to short-circuit that biological pleasure system is engaging in what philosophers like Michel Foucault call “limit-experiences,” acts that put you in grave danger in order to force you to recognize the edge of your subjectivity by confronting it with its looming end. When the brain perceives peril, it releases adrenaline and other substances that cause you to hyperfocus while producing a burst of energy, followed by joyful relief when the moment subsides.

Reflecting on this state, people say that they “never felt so alive.” The vividness is why we love rollercoasters and scary movies. In a world that alienates us from ourselves and others, the intensity is intoxicating. But despite it feeling like it, these are not meaning-making experiences.

That Sinking Feeling

When Brian Weed, a cameraman for the Discovery Channel, accompanied Ocean Gate’s CEO Stockton Rush on a test-dive of the Titan, a number of failures occurred, from a malfunction in the thrusters to communication problems with the mothership. Weed asked what would happen if the submersible, which was bolted shut from the outside, had to surface during an emergency far from the mothership. “Well, there’s four or five days of oxygen on board,” Rush answered casually. “What if they don’t find you?” Weed asked. Rush cavalierly answered, “Well, you’re dead anyway.” Rush was seeking a rush, the thrill of adventure under the threat of death, a classic limit experience.

But Rush took it to be more, contending that innovation is always meaning-making. In his words, doing something that has not been done or doing it differently “adds value to society.” Thus, anything, like regulations, that hamper innovation is intrinsically bad. “I’d like to be remembered as an innovator,” Rush said in an interview, “I think it was General MacArthur who said, ‘You’re remembered for the rules you break.’ And I’ve broken some rules to make this. I think I’ve broken them with logic and good engineering behind me. It’s picking the rules that you break that are the ones that will add value to others and add value to society, and that really, to me, is about innovation.”

Rush will indeed be remembered for the rules he broke.

There’s Innovation and There’s Innovation

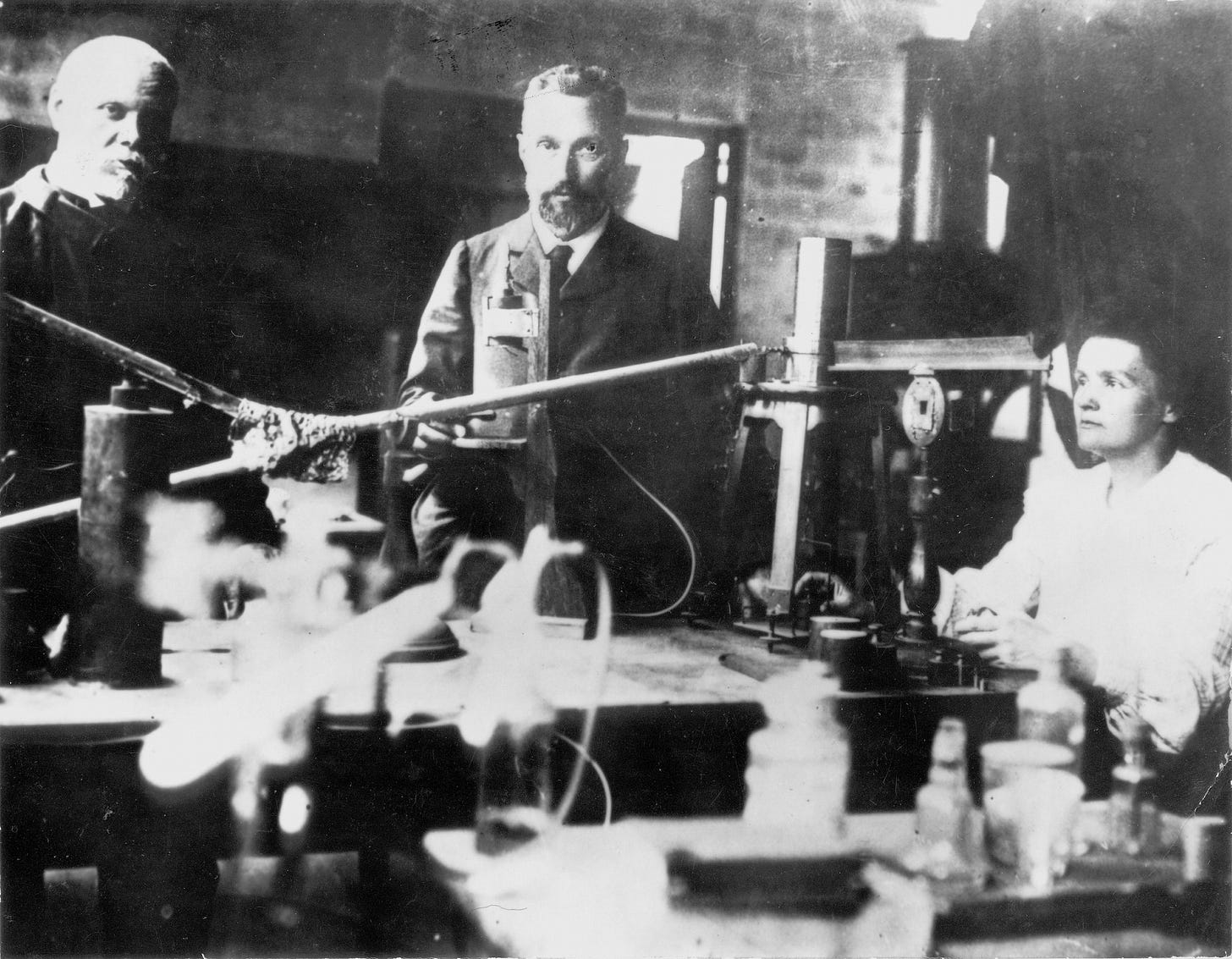

Image: Pierre and Marie Curie in their lab

Innovating can be meaningful. Jonas Salk’s life was meaningful for developing the vaccine for polio. Marie Curie’s in discovering Radium. Jane Goodall’s in finding social behaviors among chimpanzees that were thought to only belong to humans. Many celebrated individuals made meaning by undertaking dangerous activities, paving the way for human progress. But the hole-filling in these cases came from the fact that these historic undertakings stemmed from a humanitarian impulse, innovating for a purpose, for others, not just for the thrill.

Rush chafed at the constraints from regulation, at the concern for safety. He lashed out, “At some point, safety just is pure waste. I mean, if you just want to be safe, don’t get out of bed. Don’t get in your car. Don’t do anything.”

But safety regulations exist for a reason. Each rule was put in place because there had been a situation in which doing otherwise caused unnecessary harm to a real person. Do these regulations constrain innovation? Yes. Indeed, that is exactly their point. Those regulations establish the line between innovation for the greater good aimed at human flourishing, on the one hand, and innovation for vainglory, mere cognitive cocaine, on the other.

Whether it is billionaires under the ocean, billionaires in space, billionaires challenging each other to cage matches, or ordinary colleagues at work, the impulse to exceed oneself by stealing another’s glory, to surpass the here and now, to leave the world we all inhabit, seems to them to be the key to filling their gaping hole.

It’s the Little Things

But that is not where meaning resides. The hole is not filled by overcoming our humanity—in becoming gods capable of doing what mere mortals cannot. Rather, it is in discovering the profundity hidden within the normal, in the depth contained within the ordinary, in embracing our flawed, limited nature and gaining insight into who we are.

Two philosophers left the trenches of World War I committed to this, throwing away their university professorships to focus on the ordinary affairs of life. Franz Rosenzweig and Ludwig Wittgenstein could have been highly effective trophy hunters, but they chose otherwise. In a letter to his mentor, Professor Frederick Meinke, Rosenzweig wrote, “The small…thing called [by Goethe] ‘demand of the day’…the struggles with people and conditions, have now become the core of my existence…Now I only inquire when I find myself inquired of, inquired of, that is by [people] rather than by scholars. The questions asked by human beings have become exceedingly important to me.”

Sadly, “the questions asked by human beings,” the search for meaning within the simple, is largely neglected. Indeed, our society has heaped fame and glory on those who most celebrate the rejection of the ordinary, seeking to place themselves as billionaire innovators above the rest of us, living lives completely disconnected from lived reality, supposedly creating a brave new world. From this constant praise, they have wrongly come to believe that if you have enough money, you can buy any trophy.

But filling the hole in your soul, making meaning involves a connection to the lived experiences of others, not placing yourself above them. Fortune, in this case, led to misfortune, needlessly ending five lives. We mourn for them as fellow humans, but as teachers and philosophers, we wish we could have taught them otherwise. They did not need to visit those depths to find true depth.

Excellent!

Important article .

A timely reminder that it is possible to have too much of a good thing.

These men could have done so much good for the world.What a loss.