The Saw Films and the Morality of Horrible Choices

Wresting the good out of two bads.

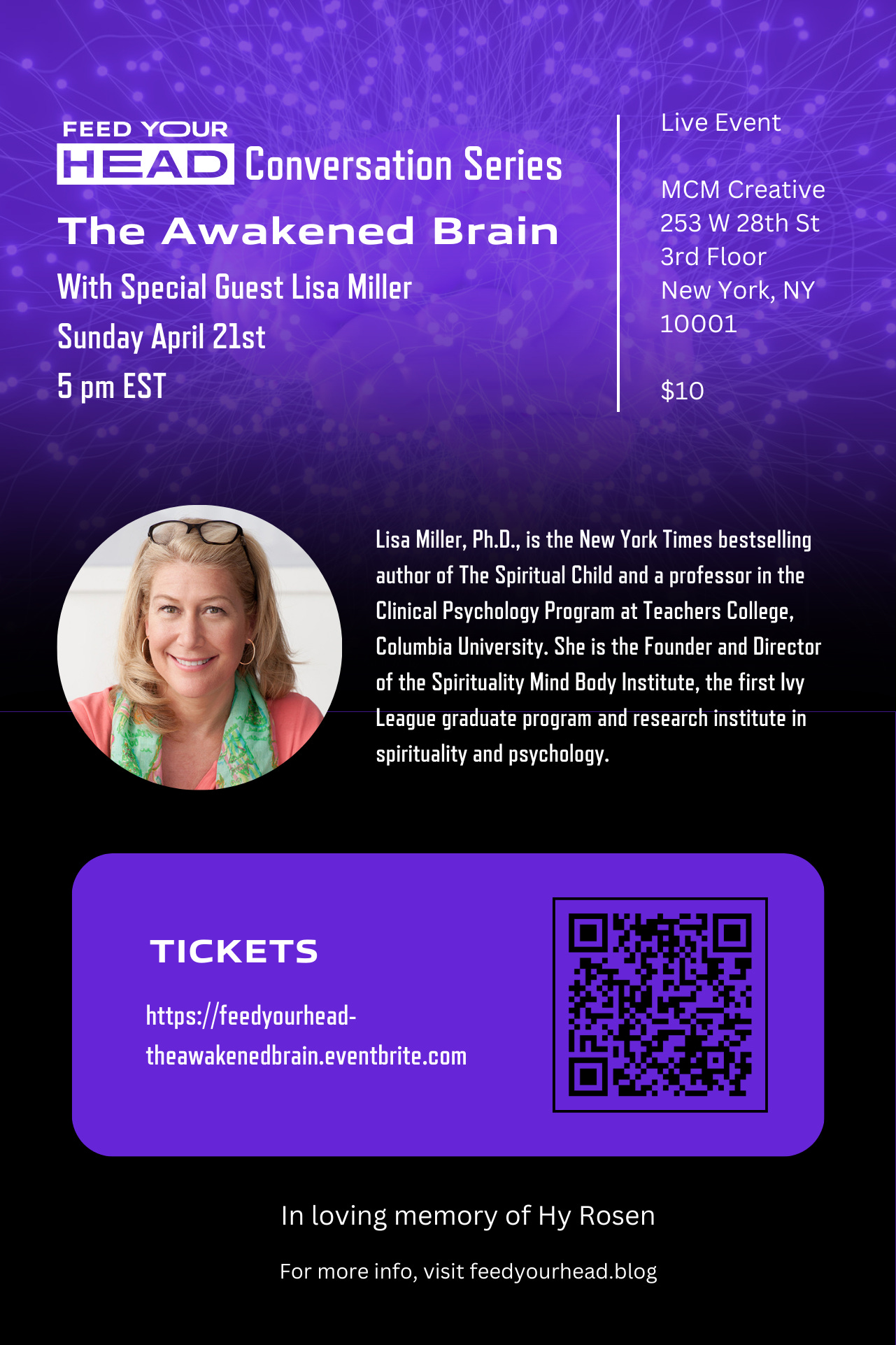

Check out our live event “The Awakened Brain” with Dr. Lisa Miller in NYC this Sunday. Flyer below…

Image: wallpapersafari.com

Have you ever been in a situation in which you were suddenly forced to make a life-and-death decision—one that would permanently affect not only you but others as well? Many of us may have wondered how we might react in these extreme circumstances and what ideas and feelings would inform our choices when the clock is ticking, and we have no one to turn to for help or guidance.

Recent events have plunged my thoughts into this sort of contemplation. In considering them, specifically the morality of horrible choices, my mind alighted on the Saw film franchise. Saw is a grotesque but immensely popular series of films (they just released the 10th) that tells the story of John “Jigsaw” Kramer, a maniacal killer genius whose elaborate traps or “games” are designed to generate extreme conditions for moral choice for his victims.

Jigsaw carefully selects these victims by observing their lives, noting their moral failings, and subjecting them to the “games,” not as retribution (as he sees it) but as a “reawakening.” By his lights, the extremity of the reality, as presented by him, offers the victims the opportunity of instant change—for better or worse.

Image: The Shotgun Carousel Trap, aminoapps.com

A good example is the “Shotgun Carousel” game of Saw VI. William Easton was the manager of a health insurance company that had caused the deaths of many sick people by denying coverage for dubious reasons. William discovers six of his colleagues who had participated in the scheme chained to a schoolyard carousel that rotates its riders, one by one, in front of a loaded shotgun that will discharge in a matter of moments, killing each in turn. William is offered the chance to save two of them by depressing two red buttons simultaneously, but in so doing, he must impale his hand on a metal spike as “a sacrifice” to show that he has blood on his hands. William makes his choices; two are saved, and four die. It’s pretty awful.

But wait. Can’t we say that this imaginary scenario is just a false dichotomy? Isn’t there always some other way? Perhaps William could have appealed to Jigsaw for mercy, noting their common humanity and pointing out that two wrongs don’t make a right. Maybe William might conclude that Jigsaw has been wronged in life by those who have more power and privilege and offer to take concrete steps to narrow that gap. Sadly, there was no time for any of that, (Jigsaw would have been unimpressed in any event), and all seven would have ended up dead. Given the parameters of the actual reality, William did the right thing, the moral thing, in this situation.

The difficult truth is that sometimes there are simply no good options. Like naive fish suddenly snared by a net they couldn’t foresee (or even imagine), any of us could wake up in a reality that we are powerless to alter. Jigsaw had his way of thinking—one that had an internal logic but that the majority of humanity would consider utterly depraved. With such a person, there can be no negotiation, no common ground to uncover, no reasoning, and no incentivizing. The cruel realities he devised for his victims were non-negotiable. The only real choice is to choose the least evil option.

Image: John “Jigsaw” Kramer, pixelgram.co.uk

To analogize this to current events, there are actors on the global stage who do not think like you and I. What constitutes a “good” for them would strike most people as a grave evil. Kindness towards them is viewed as a weakness to be exploited, and no concession (land, money, honor, et al) would suffice to arrest their evil designs.

It is a painful truth in that it forces those who are caught in their “game” to make a horrible choice—their own lives and the lives of their children or the lives of the enemy—only one side will survive the game, and even the survivors will have permanent physical and emotional scars. Like the horrific testing ground of Jigsaw’s traps, the scenario has no additional options. The good can only be selected from two bads, but good it still is, despite its relativity, despite its objective horror.

Those who would seek another remedy, to “negotiate” with the non-negotiable, including in this case either the circumstances set up by the antagonist or the antagonist himself, is to disconnect from the situation’s realities, to prefer an inaccessible, unworkable, and impossible alternative to the objective circumstance because it feels heroic and correct to pursue it, despite its odds of success. To follow through on such a Hollywood-influenced quest despite its disconnection from reality inevitably leads to greater cruelty, greater suffering, and greater immorality.

To paraphrase the Babylonian Talmud, “to be kind to the cruel means we will end up being cruel to the kind.” And the kind don’t deserve the cruelty.

![[48+] Saw Wallpaper Jigsaw - WallpaperSafari [48+] Saw Wallpaper Jigsaw - WallpaperSafari](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!08r_!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ff73cb1a3-7b10-4005-b46a-c8d6db2d3d5e_900x600.jpeg)

AMEN! HAMAS has got to go. No if, ands, or buts about it.