The Other Copernican Revolution

How the astronomer wanted to help humans to grasp the "supreme design."

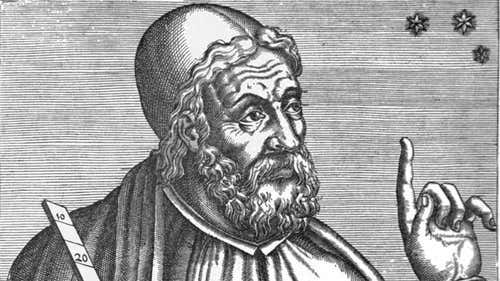

A doctor, lawyer, diplomat, linguist, statesman, mathematician, astronomer, artist, Church canon, theologian, and scientist, Nicolaus Copernicus was one of the preeminent polymaths of his age. The scientific theory that Copernicus proposed literally changed the world. Yet, the popular version of his story—that Copernicus “dethroned the Earth from its privileged position” and consequently “was murdered by the Church for revealing scientific truths”—contains more myth than fact.

Copernicus was a man of deep faith who wanted to construct a model of the cosmos that was more reflective of the genius and glory of God than the model which was the standard of his day. Far from being persecuted by religious authorities, though, Copernicus was positively encouraged by them to publish his theory—even though it did not fit with the best scientific data that was known at the time.

The Cosmological Cultural Context of Copernicus

In the year 1400, the majority of European astronomers and natural philosophers assumed a view of the cosmos that derived from the work of the 2nd-century Alexandrian geographer and astronomer Claudius Ptolemy. The Ptolemaic model of the universe was a mathematical refinement of Aristotle’s theory that was developed four centuries earlier. According to Aristotle, the spherical Earth rested motionless at the center of a cosmos where a series of concentric crystalline spheres—to which the Sun, Moon, and the five visible planets were attached—revolved around the terrestrial sphere on a daily routine.

Upon the outermost sphere were fastened the fixed stars, which also rotated daily from east to west. Beyond the sphere of the immutable stars lay the unchangeable heavens. Aristotle’s theory of physics and the associated motions of the five elements—earth, air, fire, water, and aether—depended on his model of the cosmos. All material elements (made of earth) went down, air and fire went up, and water spread out horizontally.

The gods—which we call the Sun, moon, planets, and stars—existed in the realm of eternal and incorruptible aether. And the most unchangeable being of all—Aristotle’s Unmoved Mover—existed beyond the outermost sphere of aether. Humans were stuck in the middle with all the material muck in the much undignified center of the cosmos.

While Aristotle’s nesting-doll model of the cosmos had a certain symmetrical beauty and philosophical elegance, it did not correctly correspond to how the five wandering gods (the planets) actually moved. Ptolemy thus reformed Aristotle’s system to give it more predictive accuracy, but in doing so, he damaged both its symmetry and its elegance. To allow for accurate predictions of the planetary movements and to better explain the observed patterns of brightness, Ptolemy needed to add epicycles—or additional spiraling movements—onto the circular paths of the planets.

The result was that the planets’ paths were no longer perfectly circular—as was required by Aristotle’s physics of motion—but rather something like the trajectory outlined by a corkscrew. To adjust for the differences in the observed motions of the planets, Ptolemy also had to shift the location of Earth from the center of Aristotle’s physical model. Introducing a number of fundamental discrepancies between his own mathematical model of the universe and the physical cosmic system of Aristotle, Ptolemy passed down a paradox to succeeding generations. To accept Ptolemy’s mathematical model as physically literal would be to embrace a disharmonious and monstrous mess.

Rejecting Ptolemy’s Monstrosity as Unworthy of God

Image: newscientist.com

In a letter to Pope Paul III, Copernicus referred to “the Ptolemaic system, with its eccentrics, epicycles, and treatment of each planet separately,” as a “monster.” Observing through faith that the cosmos is “created by the best and most systematic Artisan of all,” Copernicus firmly believed that both the mathematical structure and physical reality of the universe “should be harmonious.”

Seeking to theologically, mathematically, and physically reform astronomy and resolve the monstrous Aristotelian-Ptolemaic discrepancy, Copernicus suggested that the Sun—and not the Earth—is the center of the cosmos. In the heliocentric cosmos of Copernicus, the Earth rotates on its axis once daily and revolves around the Sun along with the other planets in perfectly circular orbits.

For Copernicus, astronomy was the supreme discipline whose mathematical realism allowed observers to grasp the wisdom, beauty, and symmetry of the cosmos as irrefutable evidence for the Mind of God behind it. That is why, according to Copernicus, “the contemplation of the geometrical order established by the Supreme Logos, though it required a high level of mathematical knowledge, reinforced the concept of creation as the first step of revelation.”

For who, asks Copernicus, “after applying himself to things which he sees established in the best order and directed by Divine ruling, would not through diligent contemplation of them and through a certain habituation be awakened to that which is best and would not wonder at the Artificer of all things, in Whom is all happiness and every good?”

Copernicus cited Psalms 19 and 104 to exalt the “mathematical order revealing the Divine love for humans, who are made able to contemplate the greatness of His design.” For, explains Copernicus, “the divine Psalmist surely did not say gratuitously that he took pleasure in the workings of God and rejoiced in the works of His hands, unless by means of these things as by some sort of vehicle we are transported to the contemplation of the highest Good.

The Creator God of Copernicus, namely the God of the Bible, was not an Unmoved Mover emanating and generating a necessary and eternal universe, be instead, He was “the Supreme Logos creating out of nothing a mathematical harmony.” In the Revolutions, Copernicus “deemed the creation of a geometrical world as part of the revealing activity of a personal God, aiming at allowing humans to grasp His supreme design.”

Religious Encouragement versus Scientific Scruples

Religious authorities encouraged Copernicus to publish his theory of heliocentrism in spite of his scientific scruples. Copernicus did his scientific work while serving as a canon in the Cathedral of Varmia, and his fellow canons and numerous other church officials actively encouraged him to pursue and publish his findings. When Copernicus published his famous Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres in 1543, it was after many high-ranking Church officials had encouraged him in his astronomical work.

For example, in 1515, Pope Leo X (1513–21) and other church leaders sought out the astronomical expertise of Copernicus to help reform the Julian calendar. In 1533 Pope Clement VII (1523–34) was so fascinated by Copernicus’s new model that he invited his personal secretary (and Copernicus’s disciple), Johann Widmannstetter, to the Vatican gardens to give a public lecture on the subject “to the delight of Pope Clement and several cardinals.”

Then on November 1, 1536, Cardinal Nicolas von Schoenberg wrote to Copernicus saying: “I have learned that you teach that the Earth moves; that the Sun occupies the lowest, and thus the central place in the world…and that you have prepared expositions of this whole system of astronomy…Therefore with the utmost earnestness I entreat you, most learned sir, unless I inconvenience you, to communicate this discovery of yours to scholars.”

Why, then, was Copernicus so reticent to publish a complete exposition of his system? From this series of events, it is clear that—contrary to the popular notion—Copernicus did not fear persecution from the Church. The answer is that he was being cautious due to concerns about the criticism he would receive from fellow astronomers.

Why Was Copernicus Afraid to Publish?

Image: newatlas.com

Encouraged by theologians and religious authorities yet anxious about how his theory would be received by his scientific peers, Copernicus “kept refining it for over 25 years.” Had it “not been for the nagging of several prominent churchmen,” explains historian of science Laurence Principe, “it might never have been published.”

Indeed, comment historians of science Ronald Numbers and David Lindberg, “If Copernicus had any genuine fear of publication, it was the reaction of scientists, not clerics, that worried him.” And there was a good reason for this – “Copernicus had no new evidence to justify his theory; rather, he thought that his view had more internal coherence and greater explanatory power than Ptolemy’s.”

Long before Copernicus ventured to ponder the direction of the Earth rotating around the Sun, several key medieval philosophers of nature had already discussed the issue of relative motion and the possible rotation of the Earth. Among them were the famous natural philosopher and professor of the University of Paris John Buridan (1300–62), the fourteenth-century Bishop Nicole Oresme (who argued that the observable data and physics alone could not demonstrate whether or not the Earth was rotating), and the fifteenth-century Cardinal Nicholas of Cusa, who—as the most theologically orthodox theologian of his day—freely discussed the motion of the Earth and the concept of a universe without a physical center.

Thus, by the time Copernicus came onto the scientific scene in the early 1500s, there was no reason to think that the reappearance of the idea of a moving Earth would cause a theological controversy. Indeed, in the opinion of almost everyone who left a written record, the idea of the Sun as the center of the cosmos was more theologically beautiful than the Aristotelian-Ptolemaic model.

Regardless of its elegance and beauty, however, a new theory would require a new physics to account for the various types of motion explained by Aristotle’s theory of the five elements—and Copernicus did not have a new physics to offer.

For empirically minded thinkers, the notion of a moving Earth conflicted with both basic physics and common sense. If the theory of Copernicus were true, “then the human senses would be lying to us,” and many “regarded as absurd that the senses should deceive us about such a basic phenomenon as the state of the terrestrial globe on which we live.”

Moreover, the astronomers of the time knew that if the Earth revolves around the Sun, then the stars should exhibit parallax—a slight shift in their apparent relative positions as the Earth travels from one side of its orbit to the other. But no stellar parallax could be detected. This meant that either the Earth was not moving or the stars were incomprehensibly far away.

Copernicus estimated Saturn’s sphere to be about 40 million miles away, but the lack of stellar parallax meant that the stars would have to be at least 150 billion miles farther out. While Copernicus had a theologically elegant, philosophically harmonious, and mathematically robust theory, he had not developed the new physics that was needed to support his theory and he had no empirical proof by which he could demonstrate the Earth’s motion and resolve the problem of stellar parallax.

Putting his scientific caution aside, Copernicus was finally convinced to publish a full manuscript of his theory after the Wittenberg astronomer Georg Joachim Rheticus published a summary of Copernicus’s ideas that was well received. And when Copernicus’s On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres was printed, “the book’s appearance did not unleash the criticism Copernicus feared.”

As historian of science Owen Gingerich explains, “The immediate response to Copernicus’s Revolutions was mild. No serious attacks were mounted against it, nor did it receive any immediate flurry of support. Scholars and libraries across Europe purchased the five hundred printed copies of Revolutions. It seems that every astronomer who took his own work seriously wanted a copy.

A little more than 20 years later, the book was reprinted in Basel, Switzerland, and spread more widely. During the latter half of the 1500s, the name Copernicus often appeared in astronomical texts and lectures.” Although his book was widely read and discussed, because Copernicus’s heliocentric system did not fit the observational data any better than the geocentric system, few of his scientific peers were convinced.

Science vs. Religion: The War That Never Was

When Copernicus first proposed his heliocentric theory of the Earth’s motion in 1514, he was doing so within the context of a significant amount of intellectual freedom, and his ideas about Earth’s motion belonged to a long and distinguished pedigree. Religion played a proactive role in bringing his theory to light and was the key factor in spreading the theory of Copernicus throughout the world.

Copernicus’s publication of his heliocentric theory of the cosmos thus should not be seen as the first battle of the revolution fought by science against religion. Instead, it must be understood as a continuation of a conversation within natural philosophy that began within the universities of the Church in the preceding centuries.

How did the myth that Copernicus was burned at the stake by the Inquisition ever get started? This is FASCINATING!