The New Idolatry

Mistaking Representation For Reality

Image: atlantafalcons.com

We can see in professional and collegiate sports what French anthropologist and philosopher Jean Baudrillard called a simulation. Simulations are false realities that we construct, populating them with images and icons, creating rituals and rules, and minting social currencies that create desires and hierarchies.

The central element of these simulations is that they are interesting, “hyperreal” in Baudrillard’s terminology, much more exciting and dramatic than boring old real life where generally not much happens. Our simulations, on the other hand, are full of action, often sex and violence, flashing lights—anything that stimulates us. Reality is dull, but life in the simulation is so much more exhilarating…and of course it is; that is exactly why we created it.

Go to any professional sporting event, and everyone is wearing the same colors, yelling the same cheers, focused on the images on the massive Jumbotron that enlarges the brutal hits, the graceful runs, and unbelievable catches as the clock ticks down. Your heart cannot but pound audibly in your chest. The same is true of college sports, which can be thought of as a simulation of the professional counterpart, a simulation of a simulation.

Because simulations are constructed realities, the furniture we use to decorate them are symbols, what Baudrillard calls “simulacra.” The term “simulacrum” goes back to ancient times when it referred to an idol. For most monotheists, God is not a material Being and, therefore, has no physical form. A simulacrum is a physical object constructed to be worshipped, thereby misrepresenting the nature of the Divine, and thus should be avoided. In the modern context, Baudrillard argues, today’s simulacra are images, data, and memes. Symbols are representations of the thing, not the thing itself, but in our digital landscape, we often mistake the symbol for the thing represented. We take the mere symbol to be real, thus creating a contemporary idol, a simulacrum.

This is very much true in contemporary sports, where the buzzword on everyone’s lips is “analytics.” Two decades ago, professional athletics was turned on its head when it was shown that cognitive biases, ways in which our minds are naturally irrational, led to poor decision-making and that using statistics could correct this. Notions from finance that allowed sophisticated Wall Street investors to outperform the market were imported to increase the likelihood of winning championships. Everything came to be digitized. Players were no longer people but sets of numbers. The quantitative representations of human physical achievement replaced the flesh and blood athletes.

This is especially true in professional football. Each April, representatives of the teams in the league gather for the draft where they take turns selecting the best college football players to add to their rosters for the upcoming year. To facilitate rationality in making these decisions, the league created the NFL Combine, which brings the top college players to Indianapolis for a week of quantifying.

Image: marqueesportsnetwork.com

Those invited do not play football. Instead, they get weighed, measured, timed, and tested. They run the 40-yard dash, see how high and how far they can jump, and how many times they can bench press 225 pounds. They are put through agility drills. Some even take a cognitive test to quantify their intelligence. They get their abilities and attributes digitized so that they can be reduced to a set of numbers, which can then be put through each team’s algorithm so that they can then be ordered from most to least desirable—what teams call their “big board” which they will use to decide whom to draft when it is their time on the clock.

The Combine aims to quantify these young men's physical and cognitive capacities to compete on the field successfully. If professional football is a simulation, and college football is a simulation of the professional game, then the NFL Combine is a simulation of the game altogether. And the players are reduced to their analytics, the numbers that represent their real-world abilities. Hence, what is being created is a simulacrum inside a simulation of a simulation of a simulation.

And yet, it made for riveting television in its hyperreality.

On the third day of the NFL Combine this year, Xavier Worthy experienced what may be the greatest moment of his life. He became a national celebrity, with articles about him appearing in every sporting magazine and all over the Web. Having finished his season as the second-best wide receiver for the University of Texas football team, he was invited to the NFL Combine, dreaming of being drafted and having his chance to play professionally.

When it was his time to run the 40-yard dash, he clocked an incredibly impressive 4.25 seconds. The fastest anyone had run it at the Combine was the University of Washington’s John Ross, who recorded a 4.22-second run in 2017. Worthy had proven to the assembled scouts and general managers that he was blazing fast. Just two days earlier, another player had suffered a groin injury running the dash, thereby harming his draft stock and likely costing himself a lot of money, as teams would be less likely to want to invest in him. Worthy should have called it a day. But he did not.

He wanted to try to break Ross’ record. He would throw caution to the wind and try again. When he stepped up to the line, you could feel the tension and hyperreality the event created. The breath of everyone in the building and those watching on television across the country was collectively held. Worthy got down into starting position, moving his right arm behind his back. Everyone leaned in. And he was off…then the buzzer buzzed signaling a false start. Everyone, even Worthy, laughed nervously. But the second was a clean start, and he flowed down the track. The unofficial timer showed 4.22, but the official number came back at 4.21.40. He had done it. Worthy had broken the record.

The weird part is that is a record that is not really a record. In the Olympics, that would be an o.k. time, maybe a bronze medal. The Olympic record is 4.12 seconds. Indeed, he wasn’t even racing anyone. There was no competition, just quantification.

But in this simulated world inside a simulated world inside a simulated world, it was a simulacrum that meant everything for that moment. After seeing the record-breaking time, Worthy ran, arms extended over his head, mouth wide open in joyous triumph, around the facility to a standing ovation of people cheering and crying as they lowered their cell phones. Taping the events is strictly forbidden at the Combine, but because of its historical nature, the rule was ignored for this sprint. His fellow participants gave him exhilarated hugs and bumps in celebratory solidarity. The cable sports channels and online discussion boards exploded over the “news.”

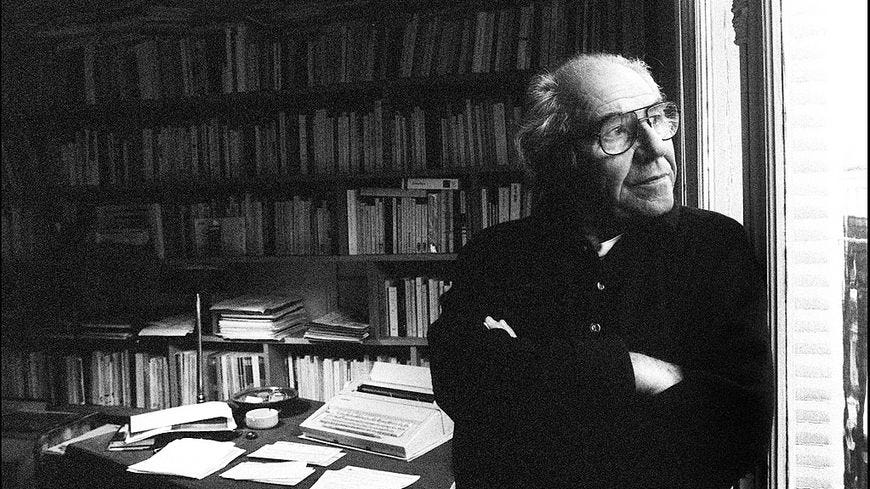

Image: Jean Baudrillard, ubicaciondepersonas.cdmx.gob.mx

Baudrillard formulated his notions of simulations, simulacra, and hyperreality as a warning. Contemporary technological life is taking us away from reality and substituting false idols. We are, he is saying, dehumanizing ourselves by allowing our symbols to become our world, ignoring the actual. And as social media and artificial intelligence warp our pictures of the world, there is no doubt there is truth to be heeded in his call.

But what was striking about the event as the TV camera panned the crowd was the authentic and overwhelming joy in the arena from absolutely everyone. Fans of all different teams—some of whom, according to the rules of the simulated NFL world, are to be mortal enemies—were united in unadulterated happiness at Worthy’s achievement. It was a fake historic moment, a simulacrum inside a triply simulated world, yet it gave rise to true collective elation.

Perhaps what Worthy gave us that is more important than a record-breaking time is the understanding that even in our false worlds that we create to hyperstimulate us, beneath all of the technological flash and the profit-driven branding, when we peel all of it back, there still beats the human heart. Even within the simulated realm, we remain connected to each other, capable of feeling each other’s joys, appreciating each other’s successes. We can find the hidden humanity within the simulation. Worthy’s number was therefore more than a number.

Yes, we must heed Baudrillard’s warning. We collect Facebook friends while less frequently seeing our actual friends. Video games facilitate violence devoid of suffering in a world in which more and more real people are becoming dehumanized and suffering. We retreat to virtual reality instead of exploring the wonders of the physical world. Artificial intelligence is writing news articles so that our understanding of the real comes from reporters who aren’t. There are concerns about our elevation of simulacra in simulations. The modern idols are being worshipped in a way that pulls us from the true.

Yet, no matter how removed we are from reality, community can still triumph. We may develop all sorts of artifices to separate ourselves and pretend we are what are not, but try as we may, we are still always the people we are. The underlying reality stubbornly remains, and the possibility of an authentic collective passion that can unite us is always there. Whether it is the community around a music group, the fandom of a movie franchise, the love of a sports team, or whatever simulations we construct for ourselves, beneath it all, it is still us who are together. The artifice of the simulation may remove us from reality, but our mutual humanity maintains the capacity to reconnect us to our real selves and each other. Xavier Worthy’s time was short, but it was also deep when we think about it.