The Monster is I

Dracula and Frankenstein for a New Millennium

Image: wall.alphacoders.com

As far back as I can remember, I have always been an avid enthusiast of the horror genre. When I was a young boy, the local public television station outside my hometown would air Friday night double features of the old Universal Pictures black and white horror films, classics such as Boris Karloff Frankenstein and Bela Lugosi Dracula, along with all their lesser-known sequels and associates. Whenever possible, I would spend the night with my aunt (three years my senior) and stay up late into the night watching the films, secure in the knowledge that my grandfather was asleep in his recliner just a few feet away, his psychotic little canine, Spot, (capable of inspiring terror in even the most vicious of monsters), sleeping beside him.

Another wisp of memory falls upon a particular week of the fifth summer of my life, in which every afternoon brought a different installment from the Hammer Films catalog of Christopher Lee Dracula films, Lee playing the infamous bloodthirsty Count more times than any other single actor. (If you thought he was creepy as Count Dooku…) Entering elementary school, I discovered the now legendary Crestwood House Monster Series, the iconic, child-friendly books with the famous orange and black covers, each dedicated to one of the institutional monsters from the films of the 30s, 40s, and 50s. Some of my earliest and favorite childhood toys were a large Frankenstein action figure and a pull-string Dracula doll (complete with cardboard coffin), along with a set of View-Master reels (catalog #B324) offering a sepia-toned, Claymation-style rendition of the Dracula story.

Needless to say, throughout this spooky season, I have been anxiously anticipating the upcoming Christmas release of Robert Eggers’ Nosferatu. My excitement was compounded when I recently learned that Guillermo del Toro, of Pan’s Labyrinth notoriety, is set to release a new cinematic adaptation of Frankenstein in 2025 as well. The contemporaneous release of new cinematic adaptations of these two narratives brought to mind the last occurrence of this one-two punch.

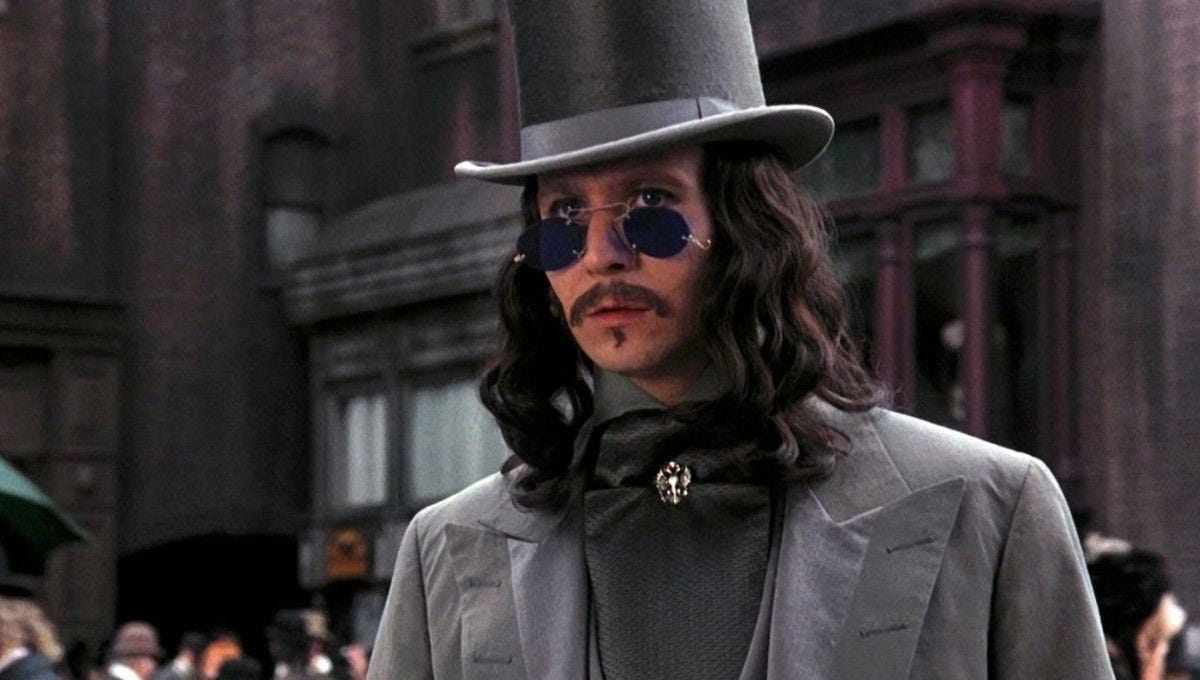

In 1992, Francis Ford Coppola directed Bram Stoker’s Dracula, starring Gary Oldman in one of his most compelling performances as the Wallachian count, alongside Keanu Reeves, Winona Ryder, and Anthony Hopkins (fresh off his portrayal of Hannibal Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs). This was followed in 1994 by Kenneth Branagh’s Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (also released by Coppola’s American Zoetrope studio—note the parallelism of the films’ titles), starring, in addition to Branagh as the monomaniacal doctor, Robert De Niro as the creature, Helena Bonham Carter, and John Cleese.

In fact, when one looks back through the history of horror, it tends to be the case that the monstrous offspring of Victor Frankenstein and the tragic Count of Transylvania appear on the silver screen at roughly the same time, nearly every time. 1931 saw the release of the Universal Pictures versions of both Frankenstein (Boris Karloff) and Dracula (Bela Lugosi), establishing what would become the iconic portrayals of these characters for posterity.

Image: consigli.it

The 1950s brought the Hammer Films resurrection of the monsters with The Curse of Frankenstein (Christopher Lee) in 1957 and The Horror of Dracula (also Lee) in 1958. Then came Terror of Frankenstein (Per Oscarsson) in 1977 and Werner Herzog’s famous Nosferatu the Vampyre (Klaus Kinski) in 1979, along with a 1979 Universal Dracula film starring Frank Langella as the Count. These were followed by the aforementioned 90s double feature and now the Eggers-del Toro versions. Why is it that every twenty to thirty years, we are gifted with a new, contemporaneous retelling of these two classic monster tales?

To be sure, contingencies of the film industry can partially explain the repeated pairings. The early success of Universal Studios’ lesser-known horror films paved the way for purchasing the rights to both Frankenstein and Dracula (hence their close release dates), and Hammer Films followed a similar trajectory with their horror catalog in the 1950s. Nevertheless, this alone cannot entirely explain why, from the vast catalog of famous monsters, many of whom found their way to the silver screen multiple times (various instantiations of mummies, werewolves, zombies, aliens, Jekyll and Hyde, the Phantom of the Opera, etc.), these two, in particular, recur with a simultaneity, an intensity, and a recognizability that the rest can only dream of. It cannot explain why, for example, Universal’s success with the horror genre began to wane in the late 1930s until a theatrical rerelease of, you guessed it, Dracula and Frankenstein in 1938 overwhelmingly resuscitated the public interest in horror films. The response was so striking that Universal repeated this dual billing in 1951 with similar results.

Certain historical elements may factor into it as well, with each of the pairings corresponding roughly with periods of significant societal shift. 1931 tracks with the early days of the Great Depression and the global economic fallout of World War 1, which was then laying the foundations for World War 2. The late 1950s saw the escalation of the “Red Scare” and McCarthyism, the widespread accessibility of television, Elvis Presley, and the birth of rock ‘n’ roll, along with the Montgomery Bus Boycott and acceleration of the Civil Rights Movement. The late 1970s followed closely the end of the Vietnam War, the Watergate scandal, the 1973 Oil Crisis, and the crisis of “stagflation,” and saw the beginnings of the reversal of Keynesian economics that would help usher in the cultural revolutions of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan.

The early 90s followed the fall of the Soviet Union, marking the end of the Cold War and what Francis Fukuyama famously referred to as “the end of history” and the beginnings of a more politically polarized media climate. Finally, now on the precipice of another Frankenstein-Dracula event, we note that, in addition to the current landscape of immense societal strife, most evidently perceptible in the rise of nationalistic movements throughout the industrialized world, we have also recently gone through a once-in-a-century public health crisis. It is certainly the case that periods of seismic social shifts foster a craving for the myths and legends most familiar to us.

But this just points us once more to the question: why these two monsters, in particular? What about Dracula and the Creature that, despite their horror, feels so comfortable, familiar, and resonant? What do they reveal about us?

Image: slate.com

Bookending the Victorian era, with Shelley’s Frankenstein released in 1818 and Stoker’s Dracula in 1897, these two iconic outcasts speak to the specter of alienation that ever haunts the cultural landscape of Western liberalism. One of the constitutive paradoxes of liberalism is the tension between the individual and the community, between the liber that posits the rational agent as the autonomous, enlightened, self-interested atomic unit of the political order and the inescapable reality that human beings are fundamentally social, dependent on one another for the basic production of our means of subsistence, for the care, education, and security of ourselves and our children, but also for our individual emotional and mental wellbeing more broadly; social networks are just as instrumental in shaping our identity as are any individual choices we make. This tension is not simply one of inside and outside, of a purely interior agent struggling with their place in the social order; it is a tension at the very heart of liberal individuality itself, of what it means to be an “I” in the midst of modernity.

The various guises of our monsters express this constitutive paradox. Some point to our social, communal nature. When the adversary is faceless, abstract, decidedly non-human, or unambiguously evil, the moral narrative is one of collective struggle, a spirit of common humanity and shared vulnerability—we’re all in this together. Such mythic monsters include zombies, mummies, aliens, and plagues. It’s safe to assume that very few people root for or identify with the xenomorph in Alien or cheer for Romero’s ghouls (not yet called “zombies”) in Night of the Living Dead. Even if zombie universes often explore social strife, the moral ambiguity is typically muted or nonexistent—we are clearly meant to cheer for one group over the others.

The 9/11 attacks are the last event I can think of that, for better and for worse, fostered a widespread sense of community in the West. I suspect that this at least partly explains the dramatic resurgence of zombies in the post-9/11 world, with such successes as Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later (2002), followed by Shaun of the Dead and a well-received Zack Snyder reinterpretation of Romero’s Dawn of the Dead in 2004. The first fifteen years of the new millennium saw a number of reinterpretations and innovations on the zombie narrative—Warm Bodies, World War Z, The Walking Dead, etc.—and the granddaddy himself, George Romero, even contributed a second trilogy of zombie films between 2005 and 2009. In perceived milieus of common struggle, our monsters are wholly other.

But if the obvious moral of 1996’s film of extraterrestrial invasion, Independence Day, was that we are, at the end of the day, capable of looking past our differences in moments of crisis and banding together as human beings to fight a common enemy, it is perhaps a fitting irony that the sequel to that film was released in the summer of 2016, as the West was revealing just how intractably alienated it really was. For a brief moment at the beginning of the COVID pandemic, it appeared as though we might rediscover some common humanity; but it was short-lived. If the COVID pandemic revealed anything, it was that in our time, there is nothing, quite literally nothing, capable of transcending partisan politics and inspiring a shared vision or sense of identity or purpose in us.

This is the landscape in which we conjure our monsters of alienation once more. The allure of both Dracula and the Creature, the reason we continue to resurrect them, hand in hand, is that, despite (perhaps because of) their flaws, we identify with them, at least in part, as emissaries of isolation. Both tragic figures, outcast, lonely, capable of feeling and expressing the profound depths of their anguish, both at odds with a bloodthirsty mob unflappably convinced of their own moral superiority, these monsters speak to our felt sense that something within ourselves is badly broken. Frankenstein’s creature (in some senses an offspring of Shelley’s own anxieties over pregnancy and motherhood) is not born a monster; in the novel, he is naturally sensitive and empathetic and even refuses, on moral grounds, to consume the flesh of animals.

He actively and repeatedly seeks even the most meager modicum of affection and acceptance. He becomes a monster only through abandonment and years of neglect, rejection, scorn, and outright betrayal by the father, who never even took the trouble to name him. It is thus fitting that popular culture often conflates, in name, the Creature with his maker, as the novel constantly probes the question of whether true monstrosity lies in the outcast or in the “decent,” “civilized” culture that creates them.

Image: indie-outlook.com

Stoker’s literary Count provides far less moral ambiguity than Shelley’s Creature. His connection to the historical warlord, Vlad the Impaler, not to mention his documented acts in the novel itself, leaves no room for doubt. Dracula (“dragon,” “devil”) is cruel, manipulative, vicious, and violent; he incapacitates and violates his victims; he is rapacious and revels in his savagery. We are not meant to sympathize with him in the way that we are with Shelley’s Creature. Yet through the compassionate eyes of Mina, there remains, even at his worst, a kernel of tragic humanity, such that upon his death, Mina can write in her journal, “I shall be glad as long as I live that even in that moment of final dissolution, there was in the face a look of peace, such as I never could have imagined might have rested there,” a peace that conveys the long-sought rest of a tortured soul, speaking to the unholy anguish of the character.

Dracula literally cannot look himself in the mirror. This motif, coupled with Dracula’s powers of hypnosis (and perhaps the early twentieth-century pervasiveness of the psychoanalytic principles of repressed desire), feeds into the initial seductiveness of Bela Lugosi’s portrayal as well as the brooding sensuality of Christopher Lee’s and eventually evolves into the later versions (Langella and Oldman) of Dracula as a man driven to heretical madness through the death of his beloved, crystallizing and solidifying the tragic dimensions of the character only barely hinted at in Stoker’s novel.

Dracula is thus the aristocratic counterpart to the homeless, nameless plebeian Creature. Together, they express a monstrosity that ails the whole of the Western social order today, from top to bottom, a monstrosity at the core of which lies trauma, anguish, heartbreak, and loneliness. In a word, alienation is the sense that something within the “I” is badly broken. Our social media silos, our toxic political milieu, a media that thrives on fomenting division, and most saliently, a global pandemic that shone a blinding light on all these factors.

But it is also the case that we must first identify our monsters in order to confront them. Through the work of art—perhaps especially in the best representations of horror—through precisely the reflection of our fragility and loneliness that these monsters convey, we might also hope to rediscover that our shared alienation is just that, “shared.” That, if nothing else, Dracula and the Creature might compel us to confront, honestly, the brokenness of our time in the acknowledgment that, in this brokenness, we are not alone. There is a Creature in us all—fragmented, nameless, abandoned, stitched together from discarded pieces bearing the scars of their past, earnestly seeking validation and affirmation. There is a Dracula in us all—heartbroken, cursed, vampirically feeding on the emotions of others, reveling at times in our cruelty and spite. These mythic forces are not out there somewhere. They haunt the heart of modern identity. They are we. The monster is I.