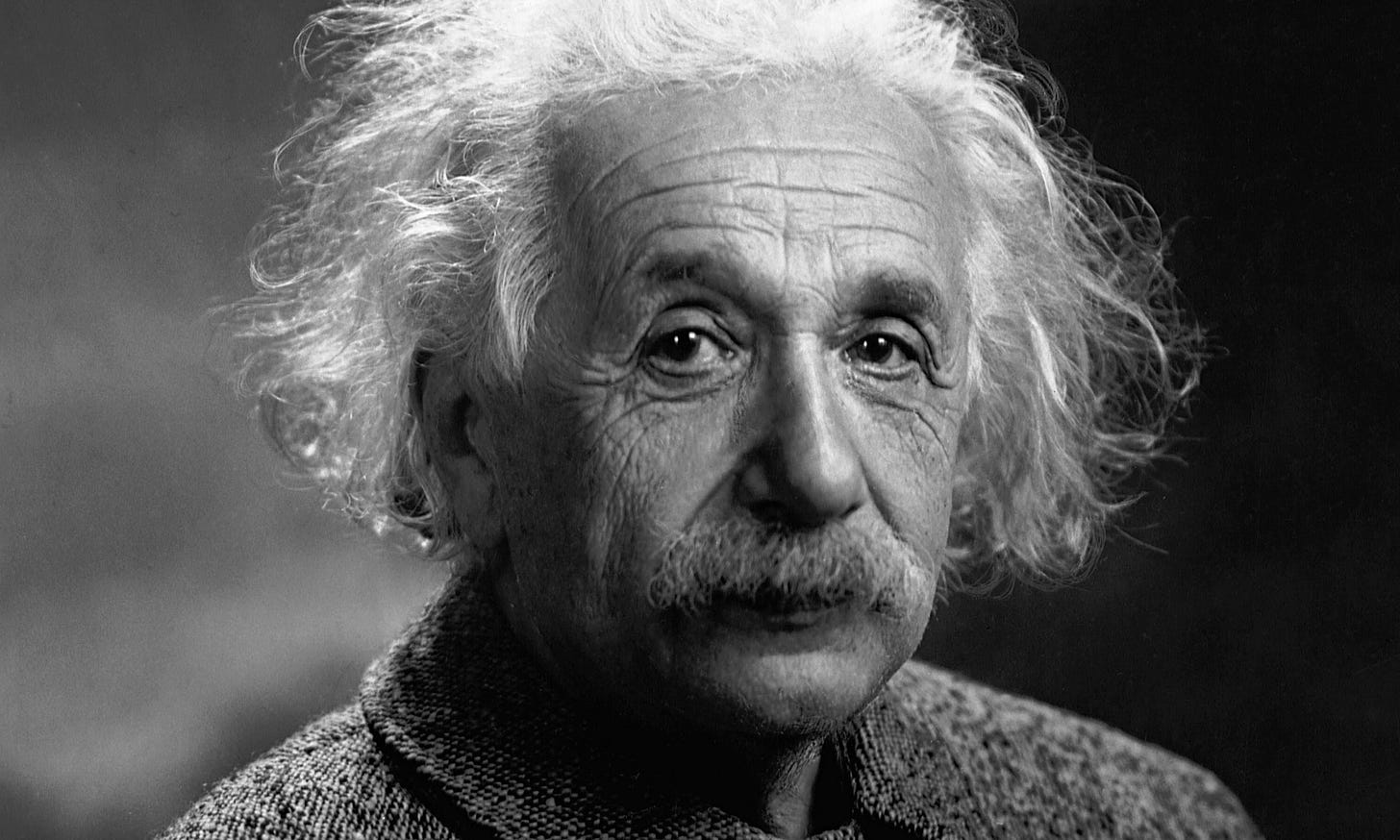

The Hidden Life Lesson in Einstein’s Theory of Relativity

What physics teaches us about perspective, truth, and living together

Image: wallsdesk.com

One hundred and twenty years ago, on September 27, 1905, the top German physics journal Physikalische Zeitschrift published the article “On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies” by an unknown patent clerk from Bern, Switzerland. That paper introduced the world to Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity. In addition to changing how we understand space, time, motion, and energy, the theory’s structure provides us with a model for living in community.

The Arrogance of the Physicists

The community of physicists of the generation before Einstein was a cocky lot, and, to be fair, they had reason to be. They had two theories that seemed to explain everything. Isaac Newton produced one to account for bodies in motion and gravity. James Clerk Maxwell unified and provided a coherent theory governing electricity and magnetism, even showing that light was an electromagnetic wave. That was the whole universe. Physics was a completed science.

Except, there were two small problems. But they were little things. Some clever person would figure them out, and physics would be over as a field of research.

One problem was the stars in the night sky. We see them. They emit light that travels through vast stretches of empty space to us. But a wave can’t travel through empty space for the same reason you can’t surf in Iowa. Water waves need water to do the waving. No ocean, no waves. So, what is carrying the light waves through space?

The answer seemed to come from Newton, who said that space is a thing. Absolute space exists independently of the stuff in it. He thought it had to, not only for scientific reasons but also for theological ones. He held that space is the sensorium of God. God literally is everywhere and knows everything because space is God’s skin. He feels the universe and everything in it.

Because that absolute space carried light waves, it was called the luminiferous aether, and finding it and determining its properties became the most crucial task in physics because that would unite the theories and complete the science. One question was whether the aether is fixed in place like a giant piece of 3-dimensional graph paper under the universe or moves like air through a fan when things move. Two experiments were conducted to determine this. One, by Hippolyte Fizeau, showed that the aether had to be dragged along, but another by A.A. Michaelson and Edward Morley determined that it had to be stationary. Uh oh. It had to be one and only one of the choices. No all of the above here.

The other problem is that what was required of this underlying space by Newton was incompatible with what was required by the space by Maxwell. The two theories didn’t play well together. They couldn’t both be right. One of those theories was by Newton, and the other was by a mere mortal, so physicists did what they could to Newtonianize Maxwell’s theory. But it wasn’t working.

Two problems that needed solving.

Einstein’s Theory of Relativity

Image: guldum.net

Einstein’s hero and mentor, H.A. Lorentz, wondered what would happen, just for fun, if we adjusted Newton's laws to work with Maxwell instead of fixing Maxwell to work with Newton’s theory. When he did the math, it turned out that objects were required to squish when they moved in the direction of motion. As Lorentz put it, it was as if they contracted because, of course, they really don’t. That’s weird.

Einstein was fascinated with Lorentz’s work and had the sudden realization that his hero had forgotten one thing in his equations…time. There was one more equation that needed adding, and when you did, you could come up with a new theory of motion to replace Newton’s. And doing so would require us to jettison those words “as if.” Things really did shrink when they moved…at least for those observers not moving with them. For those who are also in motion, nothing seems to happen.

It turns out that the same thing happens for the duration and mass. Time gets longer the faster you move, and masses get heavier the quicker you go. What we thought were objective facts of the world turned out to be matters of perspective. Developing equations based on Lorentz’s, Einstein showed how the measurable quantities would change for observers in different reference frames, that is, who were moving relative to each other.

But not everything is relative in the theory of relativity. There are some universal, objective truths that are the same in every perspective. One is the speed of light. If three people see the same beam of light, and one is moving toward the source of the light, one away, and one at rest, all three still see the light moving at them at the same speed.

Another was figured out by Hermann Minkowski, Einstein’s college mathematical physics professor. He realized that while lengths contract and times expand, they do so in a way that compensated for each other so that a 4-dimensional measure combining length and duration, what he called “the space-time interval,” will be the same from all vantage points, moving or not.

With these ideas, Einstein went on to radically transform how we see the world.

Relativity as a Metaphor for Life in Community

The theory did change how we understand the basic concepts of physics, but we can see within it another lesson, one for life. Einstein did away with the need for an absolute frame of reference, which is the only correct way to see the world. He explained why different observers would observe different things when seeing the same events.

His “principle of relativity” explicitly asserts that no observer has privileged access to being the one and only true way of seeing the world. He democratized physics by allowing all reference frames to provide legitimate descriptions of the world. He then used Lorentz’s work to explain why different observers saw the same thing differently. In doing so, we came to a larger, 4-dimensional understanding of the world.

But we don’t see the world in 4-D. We live in 3-D. Yes, the profound insight of the theory of relativity is that we need to be able to see beyond how we see the world to understand a range of other perspectives and why those perspectives see things differently to really understand what is truly going on.

Some of what we know will be objective and universal. Some truths must hold for all perspectives, and on those things we do all agree. But there are other things that we are sure of. That we measure. That we know. Yet, those will be in crucial ways dependent on how we see the world. There are other just as legitimate ways of seeing, and from those reference frames, these truths will change. Wisdom is being able to figure out which truths are objective, which truths are perspectival, and why perspective changes the ones that it does.

This is true of the physical quantities Einstein discusses, but often metaphorically true of other aspects of life. There are universal truths to which everyone should subscribe. But not everything we know is of this sort. We must be aware that certain truths are frame-dependent and will alter when you see them from a different vantage point.

This does not make them subjective. You cannot just choose what reality is. There is an explanation as to why the same thing is different from a different vantage point. Being able to see that this difference exists in this case and, like Einstein, being able to see why it changes when it changes, allows you to understand the world from the other viewpoint as well as your own. This is the first step to a broader understanding, and it is in that step that we find true wisdom.

It has been 120 years since Einstein gave us this theory. It is scientifically still relevant and perhaps metaphorically even more so today.

IMHO, I like to think that there is no "either–or" quality to existence. So many, many things are blends of various other things. What is wrong in one instance may be righteous in another instance. Is that moral relativity? How much of that is permissible without creating terrible wrongs? We all grapple with morality. It is our central reason for existence.