The Greatest Scientific Mind of All Time

On the deep faith and revolutionary brilliance of Isaac Newton.

Albert Einstein said that Sir Isaac Newton was the smartest person who ever lived and the greatest scientific mind of all time. As the most brilliant physicist ever, says Neil De Grasse Tyson, Newton possessed a genius that was "spooky"—intuitively understanding deeper levels of physical and mathematical reality in ways that appear to be beyond human capacity.

Unveiling hidden laws of nature, Newton shed light on many of the most obscure mysteries of physics and even illuminated the true physical nature of light itself. Yet, for all his love of solving scientific riddles, Newton's deepest passion and interest was in discovering the source of science itself—namely, the mind of the Creator whose infinite genius had etched into the cosmos the very logic of the laws of nature that Newton's unrivaled insight endeavored to decipher.

A Difficult Beginning

Born prematurely in 1642 on Christmas Day in the old Julian calendar, the baby Isaac was so tiny that his mother Hannah remarked that he could have fit inside a quart mug. Isaac never met his father, also named Isaac, because tragically, he died three months before his son was born. From his youth until the end of his days, Newton suffered from a variety of mental health disorders—including deep fits of mania, anxiety, insomnia, depression, autism, obsessive-compulsive disorder, bipolar disorder, and most likely schizophrenia.

As a solitary child who didn't engage in games with other children or know how to relate to them, he spent most of his time alone, building miniature machines, mills, carts, and other inventions. He experienced panic attacks and rage directed toward his family and then would experience intense remorse, making long lists of his 'sins' or wrongdoings. At Cambridge, Newton made only one friend among his fellow students, and his college notebooks document anxiety, sadness, fear, a low opinion of himself, and suicidal thoughts. Yet, from all of his suffering would arise great insight—for Newton's restless mind was tirelessly at work, and his drive towards understanding would usher in a new era of mathematics and physics.

Newton's Mathematical Discoveries

The multiplicity of Newton's scientific and mathematical genius is mind-blowing. By his early twenties, Newton had been through the work of every major mathematician in the world. Having exhausted the limits of current knowledge, Newton then advanced into unexplored territory to develop new theorems and methods. In 1665 as the Black Plague ravaged England, killing over 100,000 people, "social distancing" orders emptied campuses throughout the land, sending Newton home from Cambridge. In that same year, at the age of twenty-three, in social isolation apart from professors and peers, Newton proved what is now called the binomial theorem.

Then, over the course of eighteen months, Newton invented the fundamental theorems of differential calculus, took a break to discover the true nature of light, and then returned to mathematics to develop integral calculus. Today, many consider the invention of calculus to be "the greatest development in the history of mathematics." Without the benefit of formal instruction, Newton had become the leading mathematician of Europe, knowing more mathematics than anyone else in the world (indeed, more than anyone who had ever lived). Yet, no one at the time had the slightest suspicion that this was the case.

Newton's Revolution in Physics

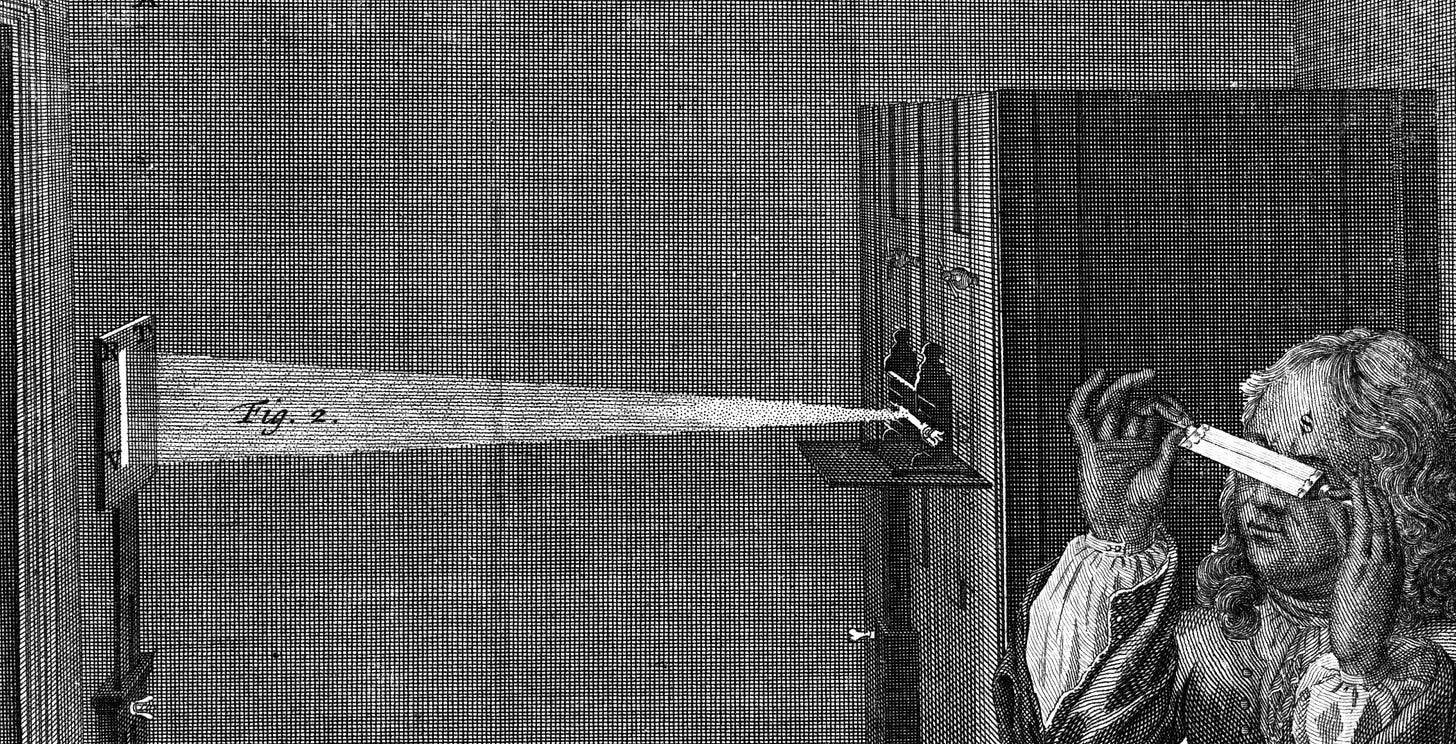

While he was taking a break from revolutionizing mathematics, Newton revolutionized the field of optics. In the same year that he invented calculus, Newton used prisms—even contorting his own cornea with a probe—to discover that white light is not a primary element within nature but composed of more fundamental colored rays that mix together.

Newton found that different objects appear to be different colors because they reflect or absorb certain colors rather than others. Applying his optical discoveries, Newton invented the concept of the reflecting telescope, which uses mirrors—instead of lenses—to collect and focus light, and he constructed a working model.

Having created a mathematical foundation in 1665 and 1666 for his scientific work, Newton then began to reflect on why objects—such as apples—fall to the earth. Newton published his findings in his Principia Mathematica in 1687, introducing the three laws of motion and his unprecedented law of Universal Gravitation. Introducing completely novel concepts, such as 'mass' and 'attraction,' in his laws of motion, Newton demonstrated:

"That all bodies continued in their state of motion or rest unless affected by some external force."

"That the change in state of all bodies was proportional to the force that caused that change and took place in the direction exerted by that force."

"That to every action there was an equal and opposite reaction."

In his formation of the law of Universal Gravitation—whereby all objects with mass attract all other objects according to a mathematical inverse square law—Newton linked the motion of planets to the motion of familiar objects.

Describing the basic laws of motion that underlie all of physics, Newton revealed that the whole cosmos operates on mathematical principles. Newton's laws formed the basis of classical mechanics and celestial mechanics in the 18th century and made possible a new physics of the Earth and heavens that is still utilized to this day.

The God of Scripture as the Foundation of Newton's Science

All of Newton's scientific and mathematical endeavors were done in service of his quest for God. Theology and the study of the Bible were Newton's most all-consuming passions, and for him, theology and science were simply two sides of the same coin. Newton affirmed that all of creation was mandated and set in motion by the Creator and that God's mathematical laws were simply waiting to be "discovered" by the human mind.

Because he assumed that God is integral to the logic of the universe, discerning how the universe worked was as much a theological quest as it was scientific. Newton saw scientific explanations, not as a way to refute theology but to understand it more deeply. Both science and Scripture were necessary for understanding the deepest riddles of the universe. Thus, Newton was even more diligent in his biblical study than in his study of science—becoming proficient in both Hebrew and Greek in order to investigate the Bible in its original languages. He even anticipated many of the findings of modern Bible scholarship.

Newton read great significance into his birth on Christmas Day, his lack of a father, and his miraculous survival in infancy. He adopted the Latin form of his name, Isaacus Nevtonus, and discovered in it the anagram, Ieova sanctus unus (the one holy Jehovah). Newton sincerely believed that God had set him apart for a great purpose and that the Creator whispered into his ear His secrets about the deeper nature of creation. According to Newton, the deepest understanding of God's creation was reserved for "a remnant, a few scattered persons which God hath chosen."

He attached a special personal meaning to a passage in Isaiah where God promises the righteous that "I will give thee the treasures of darkness, and hidden riches of secret places." Indeed, Newton saw the "miraculous" three years in which his discoveries revolutionized both mathematics and physics, as a result of such divine revelation where Newton found himself awash in hidden riches.

At the foundation of all of Newton's discoveries was a profoundly deep faith in a Creator who shaped all things through logic and reason. For Newton, the cosmos was a physical expression of the infinite power of God, and science was a window into the Mind of God. Newton's whole life was a tireless endeavor to know God more deeply. In a similar way, he believed that one could not truly understand the universe without aid from God. According to Newton, "What was needed" for clear vision in science "was ceaseless, independent erudition, and earnest prayer to God to enlighten one's understanding."

The profound beauty and rationality inherent in the creation is a reflection of the Mind of the Creator. As Newton reflects in his Principia, in the General Scholium: "This most beautiful system of sun, planets, and comets, could only proceed from the counsel and dominion of an intelligent and powerful Being…Blind metaphysical necessity, which is certainly the same always and everywhere, could produce no variety of things. All that diversity of natural things which we find suited to different times and places could arise from nothing but the ideas and will of a Being necessarily existing."

He was necessarily extremely cautious in the articulation of his philosophical ideas, as denial of the Christian Trinity was still illegal in Britain until 1813. However as he gained in stature through the recognition of his scientific achievements, he was able to become more venturesome in the expression of his thoughts. In the General Scholium to his Principia Mathematica, Newton felt confident enough to insert a brief summary of some of his religious philosophy, which can be seen to have much in common with Stoicism, and hence with Pantheism:

“...God... is omnipresent not virtually only, but also substantially; for virtue cannot exist without substance. In Him are all things contained and moved... This was the opinion of the ancients. So -

• Pythagoras, in Cicero De Natura Deorum

• Thales

• Anaxagoras

• Virgil Georgics iv 220, and Aeneid vi 721

• Philo Allegories at the beginning of Book 1

• Aratus in his Phænomena, at the beginning

So also the sacred writers: as

• St. Paul, in Acts 17.27, 28

• St. John’s Gospel, 14.2

• Moses in Deuteronomy, 4.39; and 10.14.

• David in Psalms 139.7, 8, 9

• Solomon in Kings 8.27

• Job 22.12,13,14

• Jeremiah 23.23, 24...

[refer pages 9 and 27]

[refer page 22]

[refer page 30] [refer page 48]

“...It is allowed by all that the Supreme God exists necessarily; and by the same necessity he exists always and everywhere...”

Principia Mathematica