The Divine Comedy

Why Wisdom Is a Laughing Matter

Image: flickr.com

There appears to be a conflict between righteousness and humor. Laughter is considered an embrace of the frivolous, a step away from the gravity of what we are called upon to do in this life of suffering. In the United States, our Puritan founders outlawed theatrical productions as such raillery was considered sinful. We are cleansed through our anguish. Such comic delight is harmful to our souls.

The 20th-century philosopher Henri Bergson develops this picture further, arguing that comedy requires “a temporary anesthesia of the heart.” We can only find something funny when we numb ourselves to the real pain others experience. If we were to be empathetic, the basis of an ethical life, we would not see the humor.

Yet, we also recognize the converse view—consider the laughing Buddha, the sacred clowns of the Native Americans, and the explicit admonition of Saint Thomas Aquinas, “Those words and deeds in which nothing is sought beyond the soul’s pleasure are called playful or humorous, and it is necessary to make use of them at times for solace of soul.”

The 17th-century playwright and philosopher Anthony Ashley Cooper, the 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury, argues that humor is a gift from God. To be human is to laugh. To reject this joy is to be ungrateful, to fail to actualize our full humanity as it has been given to us.

In the 19th century, however, the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard went even further, arguing that humor is necessary to prepare the human mind for wisdom. Jokes are not just a welcome respite from the harsh reality of the world but a gym that strengthens and stretches our minds to understand true insight.

Fear and Trembling (from Laughter)

Image: puttyandpaint.com

Kierkegaard does not diminish reason. Logic is a fine tool for the human mind, he maintains when we are asking about rational matters. If we want to solve a mathematics problem or cure a disease, then reason it is. However, Kierkegaard contends that the certainties of reason are only a subset of the truths there are. Indeed, he claims, they are the lesser truths.

The big ones, the profound insights of which the human mind is capable, lay beyond the bounds of reason. We may, Kierkegaard wrote, walk right up to the boundary of reason and peer over the edge. It gives way to a bottomless abyss in which the human mind can see nothing. Looking down is dizzying, causing dread and angst, fear and trembling that lead us to want to step back to where it is safe. Of course, he argues that to gain the profound truths beyond reason, one must take a leap of faith into the abyss, and while he labels the one who does a “knight of faith,” it is not mere courage that is needed. The mind must be prepared. The knight must receive training. We find the exercise required in humor.

Consider a joke: A police officer pulls over a car and sees the back seat is full of penguins. The officer tells the driver, “You need to get these penguins to the zoo!” The man agrees and drives off. The next day, the police officer pulls over the same car, and the penguins are still in the back seat. He says to the driver, “Hey! I told you to take these penguins to the zoo!” The driver says, “I did, and today I'm taking them to the movies.”

Like most jokes, this one has two parts: a set-up and a punchline. The set-up leads you to formulate a set of beliefs about how the world of the joke is. Then you hear the punchline, and initially, it makes no sense. You try to fit it into the joke world you constructed but to no avail. Then comes the a-ha moment. You realize you had something wrong and had to reconfigure the way you built the mental joke world. With that change, the punchline now makes sense. You get the joke. At that point, the a-ha turns into the ha-ha because the mental shift gives rise to comic amusement.

This is the process that Kierkegaard contends is required for higher truths. To the rational, those without the intellectual flexibility to see the world in two wholly different ways, the punchline will never fit. The joke will seem to be utter foolishness. But those capable of this cognitive yoga will see how the thing that does not fit does fit. They alone will make sense of the nonsense, and this insight brings emotional joy.

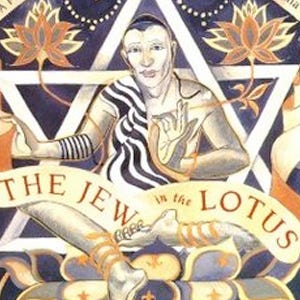

Cohens and Koans

Image: thubtenchodron.org

That picture of wisdom is like that of Judaism, in which scholars engage in a process termed “pilpul.” The books of the Torah give us laws that must be followed, but how are these abstract principles to be obeyed, performed in the complexities of the messy real world? That is the question of the Talmud in which the thoughts of the rabbis are set out, many disagreeing with each other, giving rise to seemingly contradictory understandings. Pilpul is the work needed to uncover how to rectify the inconsistent and turn up the underlying unifying understanding in the disagreement that bothers the logical mind.

Young students must study Torah and Talmud, but never alone. One must always have a “chaver,” a partner. God’s truth is too big to fit into a single interpretation, and unless one has another mind with which to engage and someone else’s perspective to enlarge your own, you will never learn beyond yourself. You must push your mind to stretch beyond its limits if you are to receive the most profound of understandings. But you cannot go beyond your limits without the aid of the other. As Jewish philosopher Franz Rosenzweig taught, there’s no objective picture without the hand of the other. Otherwise, we are held in ourselves, not engaged by the world.

We observe a similar approach in Zen Buddhism, where enlightenment requires transcending the rational. Koans are puzzles, contradictions that require a rejection of the mind fixed in the world of perceptions, which is full of illusions that distract you from moving beyond yourself. Consider “When two hands are clapped, they make a sound, but what is the sound of one hand clapping” or “If I see you have a staff, I will give it to you. If I see you have no staff, I will take it away from you.” What do these mean? To ask for the meaning is to begin on the wrong foot. Meaning is their rational dissolution. The purpose is to find their insight beyond mere logical meaning.

Finding the Funny

So it is with the jokes we encounter in day-to-day life. “You can’t explain puns to kleptomaniacs because they take things literally.” “A doctor gave a man six months to live. The man couldn’t pay his bill, so he gave him another six months.” “A father was washing his car with his son when the boy looks up and says, ‘Dad, can’t we use a sponge?’.’” Jokes bend the mind.

But the mind needs this twisting because we live in a twisted world. You will miss the real wisdom if you only see things in one way. True insight comes from being able to see things in more than one way at the same time. Jokes take us into the world, away from our subjectivity. A joke is always for the other.

Understanding this means that when we joke, we are not making light of problems, dismissing them as mere chuckle fodder. Hard problems require intricate solutions, meaning we must think about them in new and different ways. How do we prepare the mind for doing this? The answer is what the bartender says when Kierkegaard, Maimonides, and the Dalai Lama walk into a bar.