The Death of Effort

John Henry, Willy Loman, and the ChatGPT Student

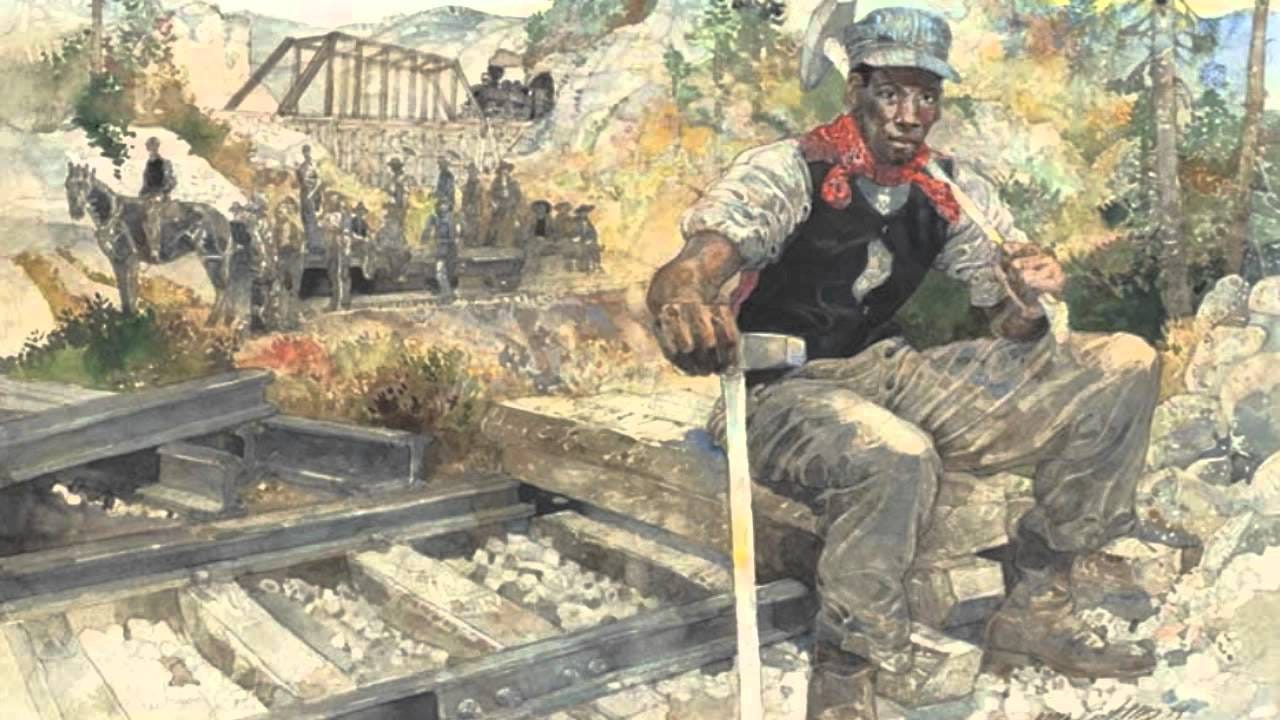

Image: John Henry, youtube.com

John Henry was a steel-driving man. Willy Loman died the death of a salesman. Today, John, Henry, and Willy are students leaning on ChatGPT: John for his logic homework, Henry for his term paper, and Willy for his final exam. They think they’re avoiding the fates of their legendary namesakes, but, alas, they may be heading straight for the same tragedies.

He Laid down His Hammer, and He Died, Lawd, Lawd

John Henry is a mythical figure in American history, though scholars believe the core of his story is true. He was a 19th-century railroad worker, strong and proud. His tool was a 30-pound sledgehammer, with which he drove spikes into tracks and broke rocks to carve tunnels. Henry earned every penny through sweat and muscle, making an honest wage.

But the railroad barons had other ideas. They thought machines could replace men like Henry. The steam shovel, they believed, could outperform human labor. John Henry would have none of it. As legend has it, the hammer-wielding hero raced the machine, human against not-human.

The folk song goes: “The man who invented the steam drill thought he was mighty fine. But John Henry made fifteen feet; the steam drill only made nine.” Henry kind of won, but at a cost. He worked so hard that his heart burst. Racing the machine did him in.

The story of John Henry fits in with what sociologist Max Weber termed “The Protestant Work Ethic,” according to which Calvinism’s strict anti-hedonistic ethic gets married to “the Spirit of Capitalism,” and the result is that the good person is one who works hard, is disciplined, and dedicates themself to their job. Weber quotes Benjamin Franklin’s “time is money” to illustrate this spirit.

In this way, John Henry is a hero. He makes the ultimate sacrifice for the sake of maximizing his work, for progress, for the railroad, which will connect America and lead the nation into the next century. But, of course, he is a tragic hero. In the end, despite being the image of masculine strength and thereby health, he dies, having given it his all.

You Can’t Eat the Orange and Throw Away the Peel

The picture changed in the 20th century. Hard work may have been necessary for the American dream, but it was becoming increasingly clear that it was not sufficient. In his Pulitzer Prize-winning play Death of a Salesman, Arthur Miller paints a bleak picture of contemporary human existence. Willy Loman was a hard-working salesman, dedicated to the firm for his entire adult life.

But as he got older, Willy was no longer as successful as he was as a young hustler. The company sees him not as a human being with needs who gave his all for the good of their bottom line for decades, but rather as a mere human resource that is to be jettisoned when no longer effective. He is not part of their family; he is just a tool, a mere object cast aside when he no longer maximizes income.

Death of a Salesman is just as tragic as the story of John Henry, but for a very different reason. Both John Henry and Willy Loman die from hard work making money for someone else, but where Henry lost his life as a result of his humanity being threatened by advancing technology, Loman gave his humanity to the company, which ate it up and spit it out along with what was left of him.

It’s the Hard that Makes It Great

Image: skyminds.net

Now consider the case of three students: John, Henry, and Willy. Like John Henry and Willy Loman, they live in tragic times. They are facing the worst job market for graduates in a decade. They sacrificed some of their educational years to a global pandemic. They are digital natives, having grown up in a world dominated by social media, and now a new technology threatens to change everything: Artificial Intelligence.

It is a powerful tool, one that could redefine work itself. Indeed, it even seems to help them in their educational endeavors. So, all three made use of it.

John is a very bright student, acing a difficult logic class. It is the last week of classes, final exams loom, papers need writing, and there is one last homework assignment for logic due. It is on proofs for arguments in first-order logic with relations. John got 100% on a similar assignment a couple of weeks ago that only used properties, so this one won’t be hard for him. There is no new logical machinery, just a slight uptick in trickiness keeping track of quantifiers. He’s confident, with good reason.

It turns out that if you ask ChatGPT for a proof, it will provide one. “Sweet!” he thinks to himself, freeing up time for other work at a busy time, and lets the large language model do the work.

Unbeknownst to John, the system his professor uses has a minor eccentricity, and as a result, the ChatGPT-generated proof violates a technicality…on every problem. As a result, John gets a 74% for an assignment he would have gotten a 100% on if he had played it straight. “Oh well, a laziness tax,” he thinks, realizing exactly what happened, knowing not to make that obvious error on the final exam.

Henry, a solid B-student, had a term paper due. The assignment couldn’t have been more straightforward: “Philosophers have written on everything. Pick whatever you’re passionate about—religion, science, sports, superheroes, fashion, cats, beer, whatever, and find two philosophers arguing about something connected to it. Explain their arguments, then be the third philosopher and make your own.”Henry, of course, went straight to ChatGPT. What it produced was a term paper so bland, kind of like vanilla being indistinguishable from Tabasco.

The paper was technically correct, neatly organized, and perfectly serviceable. Henry himself was nowhere to be found in the work. There was no knotted confusion one finds in most works of philosophy. Still, Henry earned an A. Or rather, ChatGPT did. And the very skills Henry will need in an AI-saturated world were never exercised, sacrificed on the altar of convenience, like someone taking an e-bike thirty miles a day, bragging about being a “cyclist,” and never breaking a sweat.

Willy is a C- student. He’s got a take-home exam. He’s done little reading in a class he cares little about. It’s just a requirement for the degree he needs to get out of the way. He loves ChatGPT because it seems so much smarter than him. He can use a calculator on his math homework; how is this different on an essay exam? It lets him turn in better work than he would have done without it. Like Henry, he received an A.

John, Henry, and Willy grew up in a world in which technology has been seen as the solution to every problem: encyclopedias gave way to Wikipedia, card catalogues to Google. Anything net-based is sure to be superior, faster, better informed, more accurate, and, best of all, much more convenient. In addition to “time is money,” they also obey “work smarter, not harder.” And if we take that to its logical conclusion, the smartest is not working at all.

The myth of John Henry and Death of a Salesman are not tragedies to them; they are cautionary tales. The Protestant Work Ethic killed John Henry and Willy Loman, all for nothing. The first one teaches you to embrace the steam shovel, not the old-fashioned hammer. The second shows you that no one cares about you, that they are not loyal to you, and so you owe them nothing; the game is rigged, so cheating becomes fair play.

But as educators, we plead “NO!” This is different. It is! John Henry worked for the Chesapeake and Ohio railroad, and Willy Loman worked for the Wagner company. Students may be doing the work we assigned, but John, Henry, and Willy are not doing it for us. They are doing it for themselves. We know that the given argument is valid, and we know more about Kierkegaard’s understanding of religion than they can tell us. We are not really asking students an honest question. We don’t need the answer from them.

The Need to Wrestle

Indeed, we don’t need anything from Henry and the others. They need to wrestle with the problem. Yes, we judge the final product, and so it seems that is the point. But it is not. It is the process. Yes, it is hard. No, Henry may not do as well without the tool. The point is not to get it right. The point is to get ‘you’ (Henry) right. Simply, Henry is not building a building; he is building a builder.

Our students are not in the place of Willy Loman. We are not eating the orange and throwing away the peel; we are trying to grow the orange, and sometimes there are growing pains…and, yes, sometimes we are the pains. Willy may say that this exam is for our class, but it is really for them. Yes, it is hard, but that is what encourages growth.

If anything, students are in the place of John Henry. His job no longer exists because of the steam drill. You think that by embracing the steam drill, you will therefore get a lucrative job as a steam drill operator. But that is not how this works. If you don’t swing the hammer, you will have no muscles.

This steam drill can learn to operate itself. Students are not pulling one over on their teachers, but rather showing their future employers that they are willing to make themselves obsolete. If they get ChatGPT to do it now—even if it can do it better—they are making the case against themselves.

Yes, it is hard, but as the character Jimmy Duggans says in “A League of Their Own,” “It’s the hard that makes it great.” Yes, this may be trying to put a square 19th-century peg in a round 21st-century hole, but we need to re-embrace the John Henry mentality. He was not muscular from steroids, human growth hormone injections, and advice from health influencers on YouTube. He got it from swinging the hammer.

So, John, Henry, and Willy, the advice is the same for all students: get swinging! That hammer may have been the death of John Henry, but not doing it may be the undoing of students soon entering the job market. Who will they become if the human innovation needed to direct AI is being sacrificed at the altar of convenience?