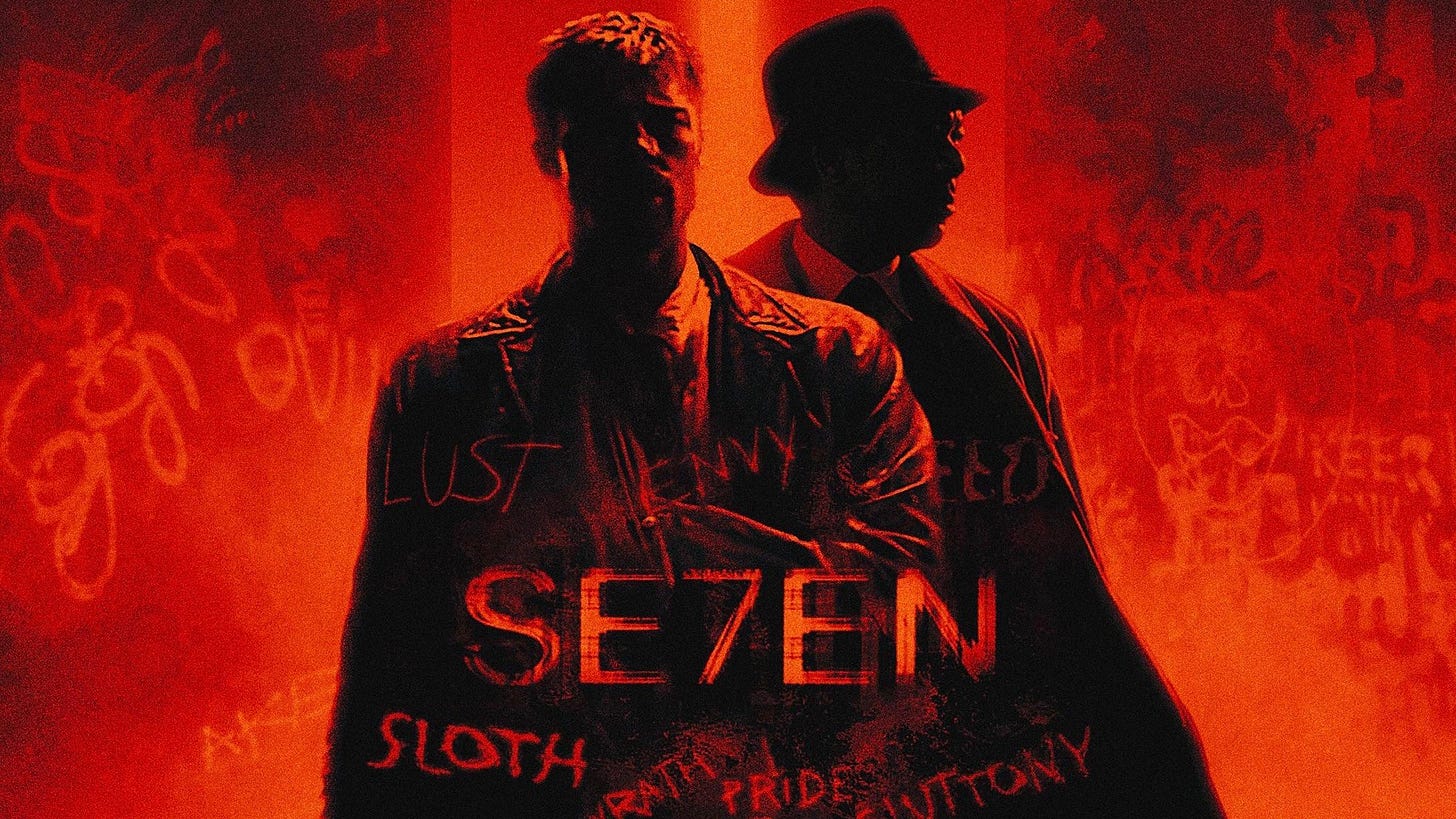

The Darkness of Se7en

The nihilism of David Fincher’s provocative horror classic

Image: The Movie Database

Se7en’s Thirtieth Anniversary and Fincher’s Raw Masterpiece

This September marks the thirtieth anniversary of the psychological crime thriller, Se7en. Released in 1995, Se7en was only the second feature film directed by David Fincher, whose criminally underrated debut, Alien3, had left a bad taste in the mouths of critics and fans alike. Though Fincher would go on to direct such cerebral films and cult classics as The Game, Fight Club, The Social Network, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, and Zodiac, there is a raw, visceral audacity to Se7en that, thirty years on, safeguards it at the pinnacle of his corpus for me.

Like many great films, Se7en defies easy categorization. It is in various parts drama, action, mystery, psychological thriller, detective fiction, and neo-noir, with just a dash of the infamous “twist” ending so popular with many films of the 90s. Set in an unnamed urban hellscape, filled with constant rain and gloomy skies, Se7en employs the familiar trope of the newly partnered detective team – the young idealist (Brad Pitt as David Mills) and his jaded, disillusioned superior on the cusp of retirement (Morgan Freeman as William Somerset) – as they hunt a methodical, sadistic serial killer (Kevin Spacey as John Doe) creating a meticulous panorama of elaborate murders organized around the seven deadly sins.

Se7en is thus one of the most provocative horror films of the 1990s. In The Claim of Reason, Stanley Cavell distinguishes between terror and horror, relating terror to a potential violence that may be done to one, as opposed to horror, which concerns a perverse threat at the heart of human nature itself: “Horror is the title I am giving to the perception of the precariousness of human identity, to the perception that it may be lost or invaded, that we may be, or may become, something other than we are, or take ourselves for…” In the 90s, the horror genre began to pull back from the trope of the superhuman slasher, a trope which, by the end of the 1980s, had become merely a comical caricature of itself. 90s horror instead began exploring the possibility that the scariest monsters look and act just like you and me.

Horror Redefined: The Ordinary Monster in John Doe

Image: YouTube.com

Se7en is certainly an occupant of this category of horror. Spacey’s Doe is as ordinary and unremarkable, to paraphrase Doe himself, “unexceptional,” as a man can be. Balding, average in both height and build, dressed in completely typical attire, he looks more like an insurance salesman than a serial murderer. Despite the intricate design of his murderous masterpiece, he’s not superhuman. When the detectives, following a lead based upon Doe’s reading habits, appear at his door, Doe responds like a frightened animal, shooting haphazardly, running erratically, diving from random apartment windows and down fire escapes.

This “setback” then forces him to, as he says, readjust his schedule. He is, as Somerset reminds Mills, “not the devil. He’s just a man.” Moreover, his anonymity, his lack of fingerprints and any discernible provenance, signifies that he is not a particular man, and not just any man, but every man, indicating that the most significant villain in the film is something deeper than John Doe himself.

In 1882, Friedrich Nietzsche issued a proclamation that is likely one of the most frequently quoted, if least understood, in Western philosophical history: “God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him.” Many a college philosophy major (a much younger version of your author included) has taken Nietzsche’s prophetic announcement to be nothing more than a poetic formulation of the banal claim that “God does not exist.” Much as this might tickle the fancies of rebellious adolescents, Nietzsche actually means something much darker and more ominous: the West has sacrificed the very foundation of its values. Worse, we haven’t recognized it yet, and because we haven’t recognized it yet, we are likely to unwittingly fill that void with something unimaginably horrifying. A dark cloud has descended upon us, the cloud of nihilism.

Rooted in the Latin word nihil, meaning “nothing,” “Nihilism” signifies the negation of values and is believed to have been coined by Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi in 1799. It was a topic of profound interest to nineteenth-century Russian authors such as Leo Tolstoy, Ivan Turgenev, and Fyodor Dostoevsky, all of whom worried greatly about the potential valuelessness lying beneath the Enlightenment zeal for abstract rationality.

But it was Nietzsche who gave the concept its most concentrated articulation: Nihilism had always hidden at the core of Western thought, and it had at last reached its fullest realization. Nihilism is an inevitable reality of our moment; it is upon us already, and bad times are a comin’. Looking at the first half of the twentieth century—the excess of the Roaring Twenties followed by the Great Depression, the advent of worldwide warfare, chemical weapons, the rise of fascism, the concentration camp, the atomic bomb…it’s difficult not to think that Nietzsche was onto something.

The real villain of Fincher’s Se7en is not John Doe, but the nihilism that this “everyman” embodies. This is the adversary with whom Detective Somerset wrestles throughout the film. True, Doe’s nihilism has a religious foundation, but then again, so does the one diagnosed by Nietzsche. Consider Doe’s project: his every creative act is an act of destruction, every affirmation a negation of life, based upon his appraisal that human existence is, in its entirety, irredeemably suffused with evil.

Nietzsche’s Nihilism and the Dark Heart of Se7en

Image: emersoncentral.com

A heaviness hangs in the air at the film’s conclusion, precisely because his masterpiece exempts no one: in the end, it is not Doe who completes the picture, but Mills, (emissary of the legal order), as Doe has successfully tempted Detective Mills into the sin of wrath, resulting in the spontaneous execution of Doe. Doe himself is implicated in his own diagnosis, as he confesses his sin of “envy,” a variation of what Nietzsche calls ressentiment. Mills’ wife, Tracy (Gwyneth Paltrow), the one seemingly indisputably innocent person in the film, has been murdered, her unborn child (a fleeting image of hope) never reaches fruition, and nothing resembling justice is ultimately served.

The sin of envy has summoned forth the sin of wrath, first in the homicidal acts of Doe, and consummated in the actions of Mills. The entire culture is shot through with putridity, and absolutely no one is left unscathed. Furthermore, inasmuch as Doe draws his inspiration from the Western canon—the Bible, Pope Gregory I, St. Thomas Aquinas, Dante Alighieri, John Milton, Shakespeare, etc., Doe manifests Nietzsche’s assessment that nihilism is the inevitable outcome of the values of Western culture.

In the mid-1990s, the nihilistic landscape of Se7en likely seemed overly and unnecessarily pessimistic. The Soviet Union had collapsed, the Berlin Wall had fallen, and Francis Fukuyama had declared “the end of history,” capitalism’s decisive triumph over communism that left no major challengers to the new world order. Home ownership (the greatest representation of the “American Dream”) was skyrocketing. The U.S. and its allies appeared to be thriving, and Western triumphalism was riding high. The future looked bright, and universal peace and prosperity seemed inevitable.

In such a moment, the darkness of Se7en must have appeared as sophomoric cynicism, the stuff of an overly cerebral undergraduate. But thirty years on, through the interminable “war on terror” and its black sites, the lawlessness of Wall Street and the collapse of 2008, the unprecedented chasm between the rich and the rest, the rapid acceleration of climate catastrophe, the widespread resurgence of fascistic movements, the concentration camp, the renewed threat of nuclear war, and a political and media climate in which “truth” is treated as nothing but a function of mass belief…it’s difficult not to think that Fincher was onto something.

Yet we would be remiss to overlook the tiny artifact of hope nestled within this diagnosis. Though Nietzsche believed that a nihilistic collapse was imminent, he also thought that, within the embrace of that “death of God” lay the possibility of recreation, the hope that human beings might one day realize their nature as the creators of values, that we might jettison our antiquated values of life denial and repression, and bring forth values of life affirmation. This is where his famously misunderstood notion of the Übermensch comes into play.

Fincher’s Se7en pulls no punches. It does not affirm the consumerist ethos of U.S. culture, nor does it hide from the pervasive rot at its core. It does not pretend that the struggle against a vapid complacency will be easy. And it certainly does not suggest that any ultimate confirmation of hope is inevitable. But if Doe’s nihilism appears all-consuming, it is crucial to note the cracks in its edifice. Doe’s self-perception is that of a holy, kenotic martyr.

As the detectives escort Doe to the desert scene of the film’s climax, Detective Somerset asks Doe for a bit of context about his life and motivation. Doe’s response is, “It doesn’t matter who I am; who I am means absolutely nothing.” To Detective Mills’ question of “What makes you so special that people should listen?”, Doe replies, “I’m not special; I’ve never been exceptional. This is, though, what I’m doing, my work,” painting himself as nothing more than a vessel for the Lord’s work, a latter-day prophet with a pious acumen, willing to engage in the unsavory but necessary labor of divine instruction.

But the reality is, Doe is not a self-emptying martyr, devoid of ego, but rather, just another “sinner,” no better than the culture he decries. His hatred for that culture derives not from righteous indignation but from his own desire to be part of it and the concomitant alienation resulting from his exclusion. His journals are filled, not with the self-disciplining introspection of the Stoics or the prayerful reverence of St. Augustine’s Confessions, but with egomaniacal and deep-seated loathing for his fellow human beings. This ressentiment lies at the root of everything he does.

His final act is not one of turning “sin against the sinner” but of stamping out the single image of goodness in the film: Tracy and her unborn child, and with them, Detective Mills's righteous optimism. The method of the rest of Doe’s crimes had been to demonstrate the spiritual “death” inherent to each particular sin by forcing each victim to carry the internal logic of their sin to its terminus.

Tracy’s Hope Against Doe’s Envy

Image: reddit.com

But Tracy is, even by Doe’s standards, innocent. She is a school teacher, a caretaker of America’s children. She is decent and kind, gentle and earnest, a loving wife, and an expectant mother. Tracy reveals her pregnancy to Detective Somerset in the diner scene, where it becomes clear that the question of whether or not she will carry the child to term is, for her, a question of whether or not to hope. To bring life into the world is to acknowledge a creature for which we are infinitely responsible, and yet, one that we know we cannot ultimately protect. It is, inherently, an act of hope.

In Doe’s final moments, he reveals that Tracy had begged for the life of her unborn child, and thus that she had answered affirmatively, in favor of hope. In a world where all appears dark, without any obvious reasons for hope, Tracy hoped nonetheless, and carried it to the end. That hope was stamped out, not by the ubiquitous wickedness of a “worldly” U.S. culture, but by the envious loathing of a single man, a man who saw that world as hopelessly unredeemable.

The nihilistic ressentiment of John Doe is contrasted with the love and hope of Tracy Mills, and though that hope is killed, that death was never an inevitability. Ultimately, Se7en challenges its viewers to affirm that love and that hope, in spite of the apparent absence of any reasons to ground it. In our present moment, nothing could be more vital. To quote the final words of the film, spoken in the mellifluous voice of Morgan Freeman, “Ernest Hemingway once wrote, ‘The world is a fine place; and worth fighting for.’ I agree with the second part.”

Fun to read. I feel like you’re missing the Greek-Tragic element, where due to dramatic irony, the viewer experiences a redeeming catharsis even though the characters themselves don’t. Maybe?

Se7en was such a dark movie I've avoided rewatching it for 30 years and probably never will. The nihilism vs optimism reminded me of a recently read Jung passage (CW 11, p509):

"During the past thirty years, people from all the civilized countries of the earth have consulted me. Many hundreds of patients have passed through my hands, the greater number being Protestants, a lesser number Jews, and not more than five or six believing Catholics. Among all my patients in the second half of life—that is to say, over thirty-five—there has not been one whose problem in the last resort was not that of finding a religious outlook on life. It is safe to say that every one of them fell ill because he had lost what the living religions of every age have given to their followers, and none of them has been really healed who did not regain his religious outlook. This of course has nothing whatever to do with a particular creed or membership of a church."

In my experience, Jung's "religious outlook" is the ineffable true and vital connection to God / Life / Reality / the Universe, which many religious traditions point to but cannot codify.