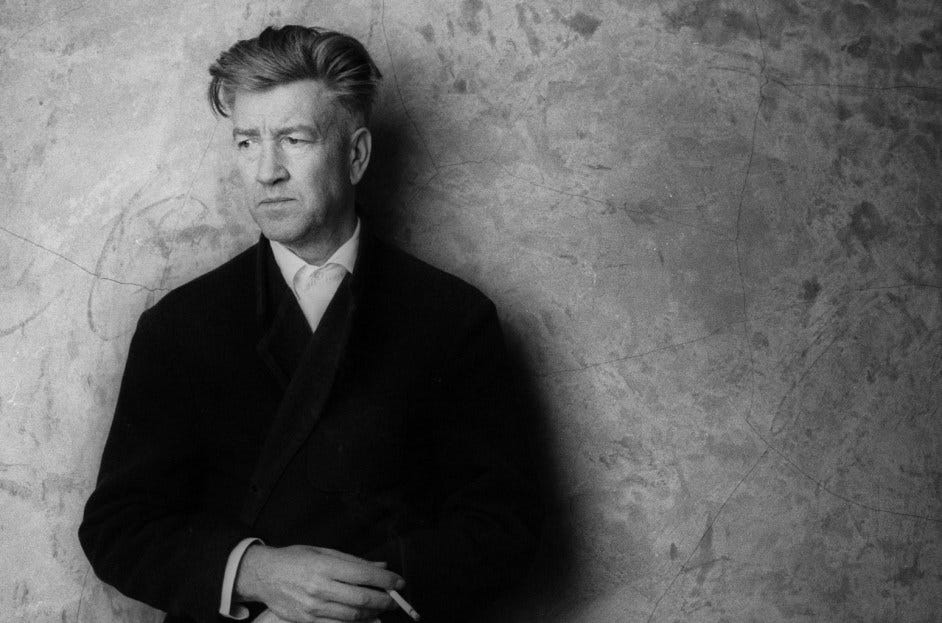

The Consciousness of David Lynch

What his life and work say about the mind.

Image: billboard.com

The great American film director David Lynch died on January 15th. In the weeks since countless obituaries and long-reads have been published, all reflecting on Lynch’s many career highs and occasional lows (which were always interesting, even when failing by other artistic standards).

Although Lynch was known for his idiosyncrasy – ‘Lynchian’ being an adjective for the surreal and uncanny – he was perfectly capable of creating great mainstream films, too. You didn’t have to be a die-hard devotee to enjoy The Elephant Man, for example, or Wild at Heart.

For many people, however – myself included – these were the gateway drugs to his stranger and darker body of work. A body of work which, for all its surrealism, is nevertheless equally and profoundly human.

I know I’m not alone in having been philosophically moved by this work, finding it intellectually stimulating, as well as aesthetically so. In my own small way, I’d like to pay tribute to Lynch here by drawing out what his life and work say about the mind.

Let's take a look.

Meditative insight

Lynch was a well-known advocate of transcendental meditation, which he began practicing in 1973.

The specifics of transcendental meditation are that it involves the silent repetition of a mantra, usually for 15-20 minutes twice daily. Otherwise, it is similar to other meditation techniques, such as mindful breathing, in that it involves a sustained but calm focus with the intention of attaining peacefulness and clarity of mind.

As with any form of meditation, transcendental meditation can cause the practitioner's mind to drift away to other concerns—what happened earlier in the day, for instance, or what we need to get from the shops later. This is simply what the mind does. The aim, however, is to return to the object of meditation without chiding oneself, and with practice, the number and duration of mental distractions should decrease.

Lynch was something of an evangelist for transcendental meditation, setting up the wonderfully-named David Lynch Foundation for Consciousness-Based Education and World Peace in 2005.

According to Lynch, transcendental meditation's main benefits are a greater understanding of the depths of the mind and reduced anxiety.

Although he was eloquent when it came to putting both of these findings into words, his mediums as an artist were primarily non-verbal: initially fine art, then film, and then later music too. Indeed, part of what makes Lynch’s films so captivating is that he channeled both of the discoveries he attained through transcendental meditation into them.

The depths of the mind

Image: rockandbirra.com

Lynch often argued that transcendental meditation opened up the depths of the mind to him.

Lynch claimed that for much of our lives, we swim in shallow mental waters and accordingly encounter only little fish. But through meditation, he says, he came to realise that this was indeed only the surface: beneath it is a vast and deep ocean, where little light may ordinarily penetrate, but nevertheless huge sea creatures dwell.

It’s a beautiful metaphor, albeit hard to pinpoint exactly what Lynch means. I suspect what he had in mind was the way in which meditation helps us to see our normal mental operations by standing outside them. In meditation, we adopt a stance that better allows us to observe our own emotional reactions, trains of thought, and habits of mind – and this can help us move past them when we ought to, attaining a calmer disposition.

Fractured selves

This reading of Lynch’s shallow waters and deep oceans metaphor does have the advantage of applying neatly to his work. Lynch’s films often defy normal narrative structure and techniques, and instead work according to ‘dream logic’. The latter may not meet our idea of common sense, but it can nevertheless make emotional, thematic, or intuitive sense.

In his films, Lynch might, for example, juxtapose seemingly unrelated images, jump around chronologically, set scenes in buildings that—were they real—defy space and proportion, or include an elliptical snippet of dialogue to illuminate a separate part of the film. More boldly still, he sometimes has his actors change characters—a device employed to brilliant effect in both Lost Highway and Mulholland Drive.

When they succeed, these surrealistic subversions of the standard rules of the film show how the neatness of conventional narrative is entirely artificial and, in fact, unrepresentative of real life. Because life does not follow a smooth narrative arc or unfold in perfectly logical chains of events, A leading to B leading to C, and so on. Equally, people do not always act in a perfectly consistent fashion, like the characters in a mainstream film.

Meditation, giving us a vantage point outside of everyday subjectivity, more clearly allows us to see how our inner lives are, in fact, disjointed and moved by forces lying outside of the conscious mind. In a given space of time, my attention can jump from the here and now to a daydream of years gone by or an imaginary notion of something that could have happened but has not – and perhaps never will. Why my mind does this is not made entirely clear to me – it simply throws up fragmentary thoughts and reveries that intrude on my engagement with the world in front of me.

Using meditation to become more aware of the hidden depths of our psyche is perhaps why Lynch’s films often juxtapose 1950s-style Americana with the surreal. Doing so reveals the former’s uncanny underbelly, the fractious and strange lurking beneath the wholesome facade. Nowhere is this more explicit than the opening scene of Blue Velvet, which begins with dreamy shots of white picket fences and freshly mown lawns before the camera descends into the grass to reveal cockroaches writhing beneath.

While our inner lives may not look exactly like a David Lynch film, even in our dreams, they bear greater resemblance than we usually appreciate.

From anxiety to wonder

Image: bestforthechildren.com

The other principal benefit that Lynch derived from transcendental meditation was to reduce his anger and anxiety. Again, this is a potential consequence of stepping outside of our immediate engagement with the world and observing the patterns of our own thinking.

First, it allows us to better evaluate our responses to situations. We can learn to think and then act more easily instead of merely reacting. Second, stepping outside our immediate engagement with the world allows us to better appreciate it. Instead of simply going with the flow of events, we can more easily see the world as the miracle that it is—and then hopefully return to engaging with it with a calmer and more mindful appreciation.

Of Lynch’s main characters, Twin Peaks’ Dale Cooper perhaps best embodies this attitude. Cooper is an FBI agent tasked with solving a terrible crime, yet he remains unflappable even while appreciating the gravity of the events unfolding around him.

Cooper’s default disposition is the kind of serenity that a life spent meditating would ideally bring. By simply being, mindfully, he is all the better able to appreciate the good things in life – even those as apparently mundane as a damn fine cup of coffee and a slice of cherry pie. Because really, there is nothing mundane about a cup of coffee: that it exists at all is wondrous and worthy of basking in.

A mindful legacy

The preceding reflections are, of course, inadequate to the task of capturing Lynch’s brilliance as a filmmaker. Entire books can be (and have been) written on that topic. But hopefully, they do shed some light on the connections between Lynch’s meditative practise and his great body of work, the former illuminating the latter.

Ultimately, that body of work – now sadly complete – stands on its own. No analysis can fully tease apart the richness of works like Eraserhead and Mulholland Drive. Instead, like all great artworks, they simply need to be revisited, reinterpreted, and appreciated anew – finding new depths with each reappraisal.

Fascinating insight about how truly fragmented our inner thoughts are. I never realized this but recognized it as immediately true.