The Allman Brothers’ Nietzschean Birth

Dicky Betts and the Ramblin Men

Image: The Allman Brothers Band, errajulul.hatenablog.com

Dickey Betts, one of the founding members of the Allman Brothers Band, passed away at the age of 80 having been an integral part of a group that redefined Southern rock through what 19th century German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche termed “triumphant self-affirmation.” The Allmans made some of the most important music of their generation by synthesizing rock, blues, and jazz in a fashion that heeded Nietzsche’s exhortation that to make history, you must break history.

Macon Music

Betts was a lead guitar player capable of blistering, lightning-fast licks that were not only technically precise but lyrical and soulful, expressive of deep human emotion. When the band’s founder, Duane Allman, told his younger brother Greg of Betts’ prowess and what he brought to the new group, Greg responded incredulously. He asked why Duane brought in Betts when Duane himself was a lead guitarist of nearly unparalleled ability. “We have two,” was Duane’s response, adding that they had a pair of amazing drummers as well. “How many bass players?” Greg asked. Just the one, he was told and Duane asked Greg to come back to Macon, Georgia to hear them practice.

Sitting in a barn listening to them jam on the Muddy Waters classic “Hoochie Coochie Man,” with Betts and Duane musically chasing each other, trading searing riffs over top of the fire-breathing dragon that was the rhythm section, Greg was blown away. When they finished, Duane asked Greg to join them on keyboards and vocals. Having experienced the power of the band, Greg declined feeling that he was not up to the challenge. After a brotherly interaction behind the barn that would likely lead to a time-out today, eventually Greg agreed and the Allman Brothers Band transformed the genre of Southern rock into something the world had never experienced.

With a string of great albums, the band synthesized styles, integrated sophisticated musical architectures, and displayed stunning virtuosity all while maintaining the profound soulfulness of blues and the southern accent with which they spoke. There was no mistaking their cultural roots in the sound, yet the music they created transcended anything the genre had ever contained.

Consider Betts’ composition “Revival” from the band’s second album. The title of the song is intended to summon to mind images of a 19th-century Baptist tent revival, a Southern tradition that brought a community together for intense prayer that would fill worshipers with the Spirit, leading to intense experiences of connection to the Divine cognitively expressed in epiphanies and physically manifested in speaking in tongues.

The rollicking riff at the heart of the piece carries listeners along in its repetition, much the way hymns do. The song’s chanted lyric, “People can you feel it, love is everywhere” has a sensibility that combines the feel of gospel music with the Beatles’ gospel of “All You Need Is Love.” “Revival” is a jam piece, with every member taking a solo in turn, each giving their spontaneous testimony to the way they are moved by the moment. The piece is simultaneously Southern rock and so much more than Southern rock ever was.

On the Uses and Abuses of History for Life

Image: Friedrich Nietzsche, vision.org

In the second of his Untimely Meditations entitled “On the Uses and Abuses of History for Life,” Friedrich Nietzsche differentiates between three different senses of history: monumental, antiquarian, and critical. Each must be understood if we are to be fully human.

This piece was written in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, where we both teach. Gettysburg College sits just a short walk from the cemetery where Abraham Lincoln delivered the Gettysburg Address, a spot just across the street from the battlefield where the Confederate troops made their only foray into the North. The cemetery is filled with markers and headstones that memorialize the war dead and the surrounding fields, once strewn with injured and dead soldiers are now filled with stone and metal monuments to them, especially to the generals who led the troops.

This is symbolic of Nietzsche’s notion of monumental history. The narratives of the past are filled with heroes and tales of the deeds that make them worthy of remembrance. In contrast to the herds of sheep who graze the fields of the farms outside of the National Park in Gettysburg, humans are capable of rising above the crowd, transcending our place, and striving for and achieving greatness. We can do what no one has done before and in doing so we make history.

These great individuals and their accomplishments deserve to be marked, celebrated, and elevated. We rightly construct monuments to their achievements because their triumph defines the outer limits of human capability and shows us how much farther we can go than we ever would have thought if we had just kept our heads down, grazing among the herd. History, in one sense, is the placing of great individuals upon a pedestal—sometimes metaphorically, sometimes literally in representation.

A second sense of the term “history” is that studied by our colleagues in the history department at Gettysburg College. They carefully work to reconstruct the way of life of a people at a time. What did day-to-day life for the Native Americans of upstate New York during the Colonial period look like one professor investigates. What were the social customs? What technologies were developed? How was social power distributed, and how were group decisions made? What did they eat? How did they marry? The antiquarian approach to history is one that captures the range of elements that made up life in that place at that time.

There is a danger in both of these approaches, Nietzsche warns, the danger of idolatry. In celebrating our heroes, we risk turning them into gods: perfected beings who should be worshiped and remain eternally beyond us. Likewise, we may take customs, rituals, and symbols and freeze them in time, seeing our heritage, and our traditions as the unchangeable essence of whom we must be. Other ways of being thereby become hostile threats to our identity. This, Nietzsche, argues is to live life backwards, to live for the dead not for the live, and therefore to take life and reject it and what it should be.

The proper approach to history, he contends, is critical. We must look at history the way an Olympian looks at a record book. The people who set the records are to be celebrated. We should learn from them, see what they had to do to be able to accomplish what they did. But their records stand for one reason only. As the new finishing line whose tape must be run through, hands aloft in victory. Their records are recorded not as an endpoint, but rather as a goal. We honor those who came before us, by destroying their accomplishments. We thank them for setting the record, by breaking the record.

And to do this, we must know who they were. We must elevate the great. Similarly, we must appreciate where we come from. There is value in our customs and traditions, accumulated wisdom and strength that we can use as a springboard to propel us forward. We are necessarily historical beings and we should take strength from the way we were raised and from the heroes we have, but that does not mean freezing them in time. Honoring them properly means transcending them, moving beyond them, and creating the new. And that requires wiping away the old to make room but doing so in a fashion wherein we see ourselves as a part of it in moving beyond it.

Every culture is valuable, but every culture is as flawed as the people who created it. We all come from communities that contain greatness to be proud of but also sins to be ashamed of. No community is faultless. No society is perfected. Humanity is a process. It creates itself by moving forward, by correcting the earlier errors, by rising above what it was and beyond what it thought it could be. That, Nietzsche held, is the proper use of history.

Thus Jammed Zarathustra

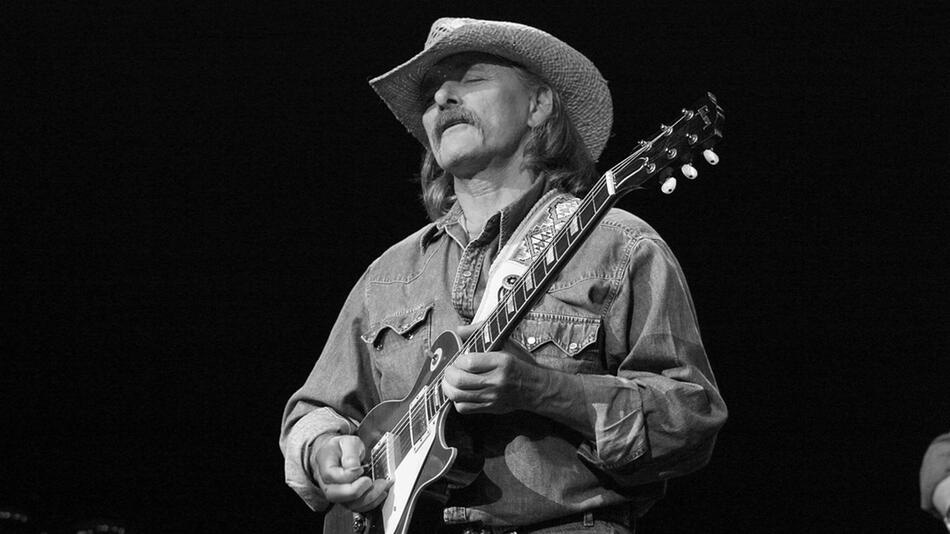

Image: Dicky Betts, web.de

And that is exactly what the Allman Brothers did. The body of work that Betts and his bandmates created respected history. Before launching into “Stormy Monday” on their Live at the Fillmore East album, Greg takes the time to honor the performer of a great version and then the composer. You cannot listen to Betts’ masterpiece “Ramblin’ Man” and not hear the influence of a century of Southern music in the notes and the lyrics. They knew where they came from, and they realized the work of the great musicians in that tradition, and they respected it all. But their approach to history was critical. They were both record makers and record breakers.

As a group from Georgia on the tail end of Jim Crow, they were racially integrated. The back cover of their third album “Brothers and Sisters” brings together the combined families of the members in a group shot. Their art made them one collective undifferentiated whole—both musically and personally—morally transcending the longstanding cultural failures of the tradition they also paid homage to. Their family was the human family without the racism that had long plagued the region.

This integrationist spirit allowed them to pull in artistic influences that were not heard in other Southern rock bands. That ability to take something recognizable and insert insights from other traditions meant that the Allman Brothers Band did things that no other group did. And in some cases, what no other band could. It was not only that they had open minds, open hearts, and open ears. That was true, but they were also talented in a way that few other groups were.

While Betts’ “Ramblin’ Man” starts as the ballad of a poor Southerner who, having been “born in the back seat of a Greyhound bus” is destined for a migratory life devoid of deep interpersonal entanglement, the end of the closing jam shows something completely different. After Betts and Duane trade scorching solos, they come together playing fast, soulfully, and most notably in perfect unison. If you had not heard their lines merge into one, you would not believe that you were hearing two people playing together.

These were the days before studio tricks could simulate incredible work like this. This was real and even on the thousandth listen still amazes the ear. The Allman Brothers Band not only did something that had not been done, they did what no one ever thought could be done. But they did it in their own accent.

The Allman Brothers embodied the Nietzschean approach to critical history, one that honors your heritage and the great individuals that spring from it, but one that drives us to improve it, to reimagine it, to transcend it. Coming out of a time and place of great division and hatred, the Allman Brothers Band asked us all, “People can you feel it?” Because love is indeed everywhere.

It's not the Greyhound bus that marks the narrator of "Rambin' Man" as a Southerner. It's the mentions of Highway 41, Nashville, and New Orleans :-)

I would argue that Revival is not a jam piece, as each instrument gets only 4 beats to signal its presence. The emphasis is on the idea that together they form an ensemble, not that all step back for extended measures while each solos in turn.

This article was an eye-opener because I learned things I had not known about the Allman Bros. When I saw them at the Fillmore East, they were so LOUD that I had to stuff my half-deaf ears with toilet paper! I wish that sound system had not been so distorted because I probably would have liked this band. I liked this part of the article: "Honoring them properly means transcending them, moving beyond them, and creating the new. And that requires wiping away the old to make room but doing so in a fashion wherein we see ourselves as a part of it in moving beyond it." No fan of Nietzche, I do agree with this approach.