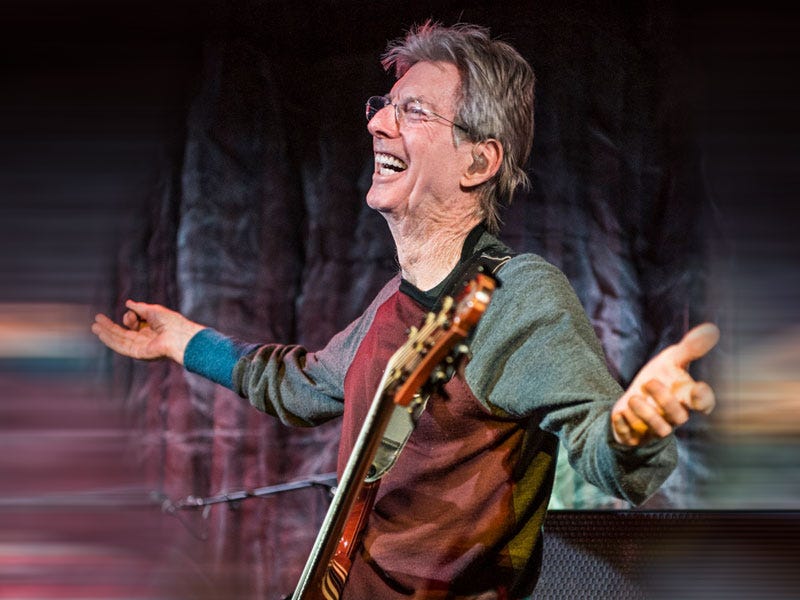

Such a Long, Long Time to Be Gone and a Short Time to be Here

A Tribute to the late Phil Lesh of The Grateful Dead

Image: greatsouthbaymusicfestival.com

Friday, October 25th, Phil Lesh passed away. Founding member and bass player for the Grateful Dead, Phil holds a special place in the hearts of fans across the globe. If Jerry Garcia was the band’s soul, then Phil was its brain. Not only an accomplished musician with a deep interest in experimental composition, he was also a committed amateur Egyptologist fascinated by the history and spirituality of the Middle East. It was Phil’s interest that led to the band playing in front of the Great Pyramid of Giza. The psychedelic 60s are often lampooned by cultural critics as bastions of mere youthful hedonism, but because of those like Phil Lesh, they were actually much, much more.

Unbroken Chain of You and Me

In his memoir, Lesh recounts his early interests in music, beginning with the violin but ultimately moving to the trumpet. The trumpet was the perfect instrument for Lesh as it led him to orchestral and jazz music, which in the Bay Area of Lesh’s youth were interestingly overlapping. It also allowed him to learn to play melody and harmony and study the ways in which they interacted.

His training in classical music led him to avant-garde composers of modern music, especially Charles Ives. Ives is considered the American Arnold Schoenberg, but unlike Schoenberg, who challenged longstanding musical conventions from the edgy culture of Europe, Ives came from a stateside foundation in which Stephen Foster and John Philip Sousa had established a more earthy, folksy palate. Ives used Americana as his launching pad, but in manipulating tonality and rhythms in ways that undermined traditional approaches to composition, he was left unmoored from standard expectations.

Lesh was fascinated by this artistic liberation. In Ives, he found someone who showed him that music as an art form may be as old as humanity itself but still provided the opportunity for exploration of the unknown.

At the same time, San Francisco and Lesh’s hometown of Berkeley were hotbeds of West Coast jazz. Dave Brubeck took jazz to college by swinging in unusual time signatures and playing with unexpected key changes, but it was Stan Kenton who was pushing it in unforeseen directions. The Kenton orchestra paired intricate charts with unusual instrumentation for jazz bands like strings and other more orchestral players. In expanding the range of tonal colors and approaches while still maintaining the swing of jazz, the Kenton Orchestra provided another influence that fed Lesh’s appetite for experimentation.

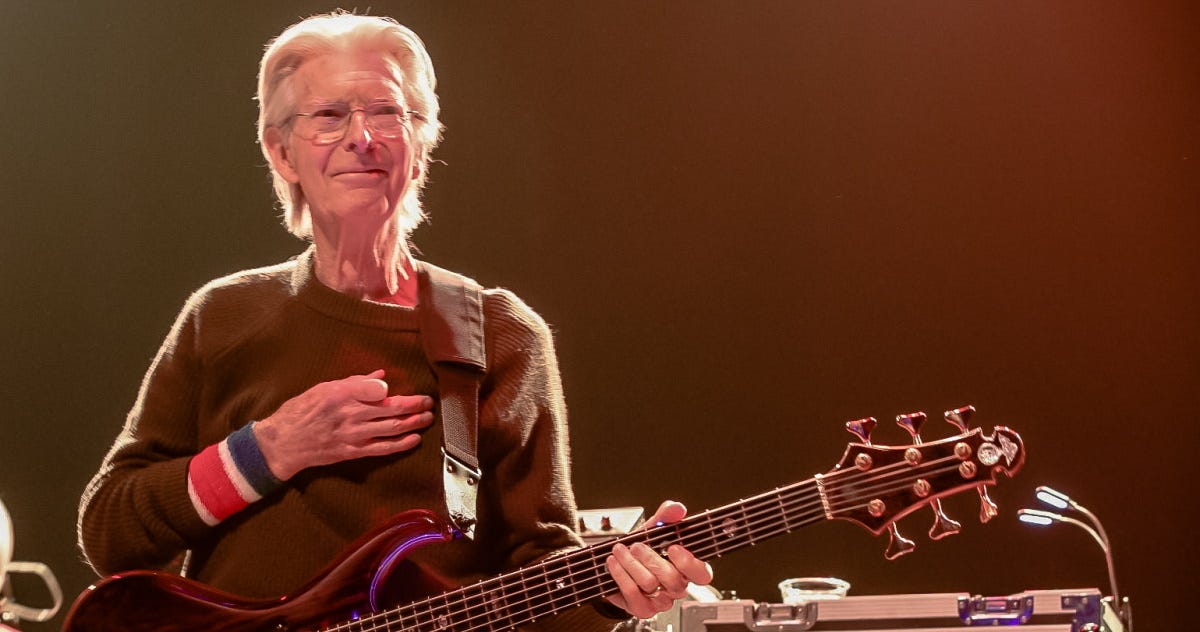

Your Silver Shining Town

Image: deadimages.com

Lesh was lured away from the horn by a banjo player named Jerry Garcia, who himself had decided to move from folk music to rock and roll. He convinced Lesh to pick up the bass guitar and join him. The band they put together, The Warlocks, featured Ron “Pig Pen” McKernan on organ, harmonica, and vocals, his gritty style providing the sort of Americana starting point that his idol Ives began with. The band began with covers of popular rhythm and blues songs of the mid-60s, but from Lesh’s intellectual interest in musical expansion, they did not merely play the tunes but opened them up to improvisational exploration.

Famously, their first gig was at a pizza parlor where the owner told them that they would never make it as a band because they were just too weird. “The song was over,” Lesh later recalled, “but we were not done playing it.” Like the works of his jazz influences, the composition was only the starting point for the performance, which required the players to become the music. The band that would become the Grateful Dead, from Lesh’s intellectual interest, was re-understanding what rock music could be. It could be art.

Their unusual approach caught the attention of Ken Kesey, who invited them to become the house band for his own ground of Merry Pranksters’ infamous Acid Tests. By dosing a group of people at a place at a time with LSD, Kesey sought a collective raising of consciousness. The band would set up, and the instruments would be available, but they were not expected to play for a given period of time. Rather, the event would unfold organically. If playing struck them as the thing to do, then they would play whatever felt right.

It seemed to Lesh that Kesey was doing for life what his musical heroes were doing for composition and performance. This lesson would become the touchstone of the Grateful Dead’s concerts. Especially in the years from 1967-1969, the openness of the jams, providing themselves the space to spontaneously compose music as it arose not from a single player but from the group and audience together out of the aether, allowed for the unplanned construction of musical worlds that all present could inhabit together. It seemed like the natural next step from the artistic liberation of Ives to Kenton to the Dead.

This Is All a Dream We Dreamed

Lesh’s fascination with the Middle East led to a spirituality that is on display in the music that emerged. The 1975 album “Blues for Allah” is clearly a nod toward the post-Egyptian religiosity of the region, and the instrumental “King Solomon’s Marbles” providing an Old Testament reference.

Their long, strange trip took them to Egypt three years later, where they not only performed among the Pyramids but, in both shows, collaborated with the Nubian-Egyptian composer Hamza El Din on a piece they titled “Ollin Arageed.” The piece began with El Din’s music sung by a children’s choir in Arabic, which was then combined with the world-influenced rhythms of the band’s drummer, giving way to an open musical exploration influenced by the unique location.

In both of these works, what we see is less of a song and more of a prayer. These fully instrumental pieces take the listener on a sonic journey that is not only experienced but also engages them in finding meaning within it. Without lyrics, we are only given the musical imagery, not told what to make of it, but as searchers, we cannot help but seek understanding within it, which only leads us within ourselves where the true wisdom ought to be sought.

Maybe You'll Find Direction Around Some Corner Where It’s Been Waiting to Meet You

When Lesh’s father died of cancer, the Grateful Dead’s songwriter Robert Hunter wrote the lyrics that became the song “Box of Rain,” which Lesh would sing on the 1970 album “American Beauty” and with decreasing frequency over time with the band live. (Indeed, it was a treat to get to hear Lesh sing back then). In the words that Lesh’s dear friend provided him in his time of loss to try to comfort him, perhaps we can now find meaning with Lesh’s passing.

Walk into splintered sunlight

Inch your way through dead dreams to another land

Maybe you're tired and broken

Your tongue is twisted with words half-spoken and thoughts unclear

What do you want me to do

To do for you, to see you through?

A box of rain will ease the pain

And love will see you through

Check out our interview with Dr Gimbel: The Philosophy of the Grateful Dead

Great read!