Springsteen: Last Man Standing

An operatic ode to the autumn of life.

Image: billboard.com

This past March, I checked off a major bucket list item when I saw Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band perform at the Capital One Arena in Washington, DC, appearing for the first time on tour together since 2017. That I was able to see them with my son, Jacob, whom I initiated into Springsteen fandom at a very young age, solidified the event as one of those indelible, almost ethereal experiences that I’ll carry with me to the end.

I didn’t really “discover” Springsteen until 2008, at the age of 32. Of course, I had always known his music, particularly the hits like “Born to Run,” “Thunder Road,” and “Born in the U.S.A.” In fact, this latter album was even a staple of my childhood, constantly spilling out the living room windows of my boyhood home over the summer of 1984. I even bought his Greatest Hits album when it was released in 1995 because, well, it seemed like something an American rock-loving teenager should own. But even then, I only ever listened to the three above-mentioned songs, and maybe, occasionally, “Glory Days.” I didn’t yet get Springsteen.

I hadn’t yet lived enough, loved and lost enough, for Springsteen to really get ahold of me. I hadn’t yet fallen upon the serious sort of midlife self-reflection that resonates in the line, “When I look at myself, I don’t see the man I wanted to be.” Springsteen was not the first of my musical favorites. But he is, without question, the most enduring, now being at the pinnacle of my playlist for fifteen years.

A curious setlist

As we walked out into the DC night, collectively processing what we had just experienced, something surprising occurred to my son and me: despite appearing in the nation’s capital, Springsteen and the band had not played “Born in the U.S.A.,” arguably the most immediately and widely recognizable song, not to mention one of the most anthemic, in his catalog.

But this led to an even more comprehensive realization: namely, the overall performance was far more introspective, containing a great deal more autobiographical reflection and narration, than I had expected going in, given the countless descriptions I had heard and read over the years of the Boss’s legendary intensity. This is not to say that the show lacked energy; on the contrary, given Springsteen’s seventy-three years, the almost three solid hours of performance, including the lengthy and dynamic “Rosalita (Come Out Tonight),” was absolutely remarkable.

But the show was not so much the erstwhile high-octane festival of his greatest and best-known hits, but rather, a musical photo album containing performative snapshots from the various epochs of the band’s five-decade-long history, “faded pictures in an old scrapbook.”

The essence of the event may best be crystallized by the introduction that Bruce gave to his performance of the song, “Last Man Standing.” At age fifteen, Springsteen told us, he had been invited to join his first rock band, The Castiles. Over the next four years, The Castiles would gain a respectable measure of local notoriety, playing venues in and around New York and New Jersey, and even recording a few original songs. As most young bands eventually do, The Castiles split in 1968; and in 2018, the penultimate living member of that original band, George Theiss, passed away, leaving only Bruce, and providing the inspiration for the track.

This recollection was the moving introduction to but a single song (which fell, perhaps coincidentally, at exactly the halfway point of the show), but the twilight embers illuminating this story were the guiding light of the entire event, ending with an acoustic performance of “I’ll See You In My Dreams”: “I got your guitar here by the bed/All your favorite records and all the books that you read/And though my soul feels like it's been split at the seams/I'll see you in my dreams.”

The weight of our goodbyes

Image: rollingstone.co.uk

It is one of the tragic paradoxes of life that, the longer we live, the greater the weight of our goodbyes, (a fact also attested by the onstage presence of Jake Clemons, saxophonist and nephew of longtime E Street saxophonist, Clarence “the Big Man” Clemons, who passed in 2011). “Black leather clubs all along Route 9/You count the names of the missing as you count off time.”

Doors close, stories end, children leave, friends die, we blink and thirty years have passed. This is, it’s true, a cliché, but another of the constitutive paradoxes of life is that, for all their apparent banality, clichés often hold kernels of truth that we can only really know once we have lived them. The late autumns of our lives, as winter’s isolation begins to make itself felt, can be crushingly lonely, can echo a solitude that language cannot touch. But music can.

To be sure, Springsteen’s work has long contained protracted meditations on goodbye. “Independence Day,” tells of the break to end a toxic father-son relationship: “‘Cause the darkness of this house has got the best of us/There’s a darkness in this town that’s got us too/But they can’t touch me now and you can’t touch me now/They ain’t gonna do to me what I watched them do to you.” Extending this theme are recurring motifs of separation from one’s claustrophobic hometown: “Baby this town rips the bones from your back/It’s a deathtrap, it’s a suicide rap/We gotta get out while we’re young/‘Cause tramps like us, baby, we were born to run.”

There are countless lyrics of despair, bidding farewell to the possibility of a meaningful future: “Now those memories come back to haunt me/They haunt me like a curse/Is a dream a lie if it don't come true?/Or is it something worse?” There are also lyrics of commemorative, revelatory goodbyes, as in “Glory Days”: “We just sit around talking ‘bout the old times/She says when she feels like cryin’ she starts laughin’, thinkin’ ‘bout/Glory days.” Bruce’s music has, in some senses, always been about goodbye. But this time feels different. For all his stunning septuagenarian vitality, Bruce is no longer a young man; and this performance was an operatic ode to the final autumn of life.

It is perhaps the clearest mark of Springsteen’s greatness as an artist that, for all its existential reflectiveness, this autumnal confession still exuberantly connects with the spirit of the audience as only a great artist can. Though he writes, sings, and plays from the depths of his own affective well, Springsteen has always done so with an imagination and vulnerability so concrete and real as to quicken the humanity in all of us. Whether singing about buying a newspaper for his father, or from the perspective of a man on death row, the vitality of human connection is unmistakable. This is no less true now, as Springsteen reckons with the meaning of his own finality, with the tail end of a life spent transforming the complexities and nuances of human experience into art.

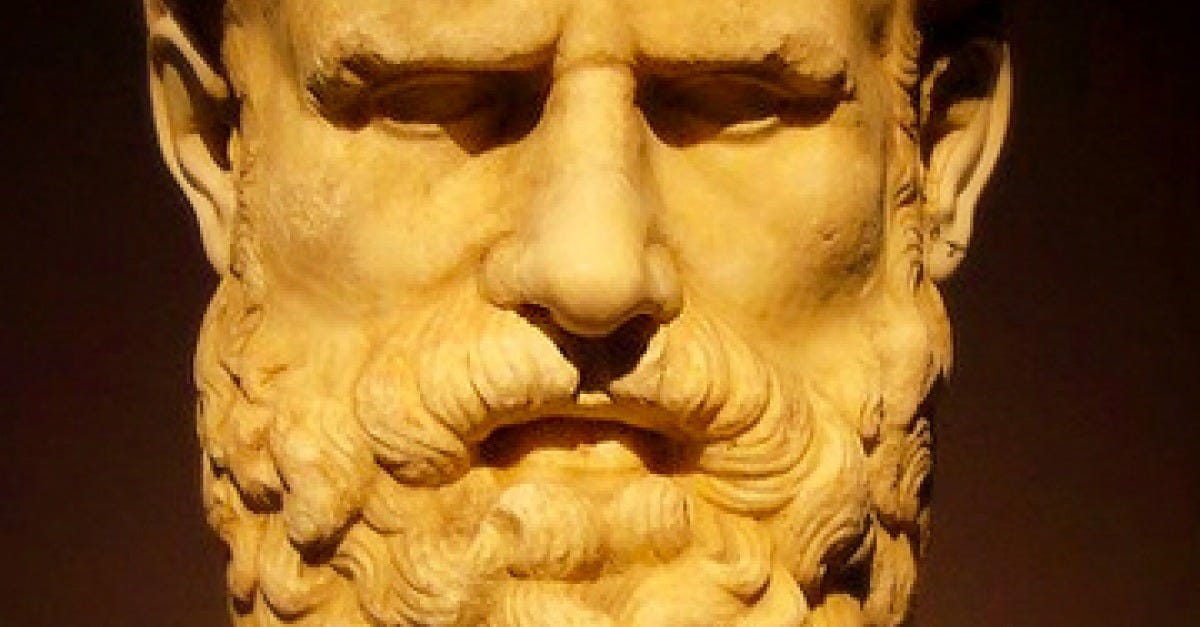

Archilochus: the warrior-poet

Image: laphamsquarterly.org

In the ancient Greek world, around the seventh century BCE, there lived a warrior-poet named Archilochus. Though his name is not widely known today, antiquity reckoned his poetic talents as comparable to those of Homer, and their names were often mentioned in the same breath. But where Homer wove epic tales of gods, kings, and heroes, Archilochus was famous for compositions of a lyrical and highly personal nature. In his first published work, 1872’s The Birth of Tragedy, philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche writes of Archilochus, “The artist has already surrendered his subjectivity in the Dionysian process. The image that now shows him his identity with the heart of the world is a dream scene that embodies the primordial contradiction and primordial pain, together with the primordial pleasure, of mere appearance.”

The mere appearance to which Nietzsche here refers, the appearance that the artist breaks down, is the sense that we are all essentially fragmented from nature and from one another. Archilochus, Nietzsche says, like all great artists, speaks so profoundly and authentically from the depths of his experience and with a sensitivity attuned to the most subtle nuances of affect that it cannot but resonate in the heart of the listener. At its best, art so deeply plumbs the subjective that it shatters the individual subjectivity, throwing us back upon the universal.

With this tour, Springsteen immerses us in this experience of finality, the inevitable reflection that accompanies our acute awareness of the passage of seasons and the closing of life’s chapters, counting the names of the missing as we count off time. It is no less joyful than the Springsteen concerts of old because it is no less expressive of the paradoxes of existence. If anything, it may be even more joyful, in that it unflinchingly celebrates, in the face of life’s innumerable losses, the enduring ability of art to connect us to the past, to the future, and to one another. It reminds us that our felt sense of loneliness is, in fact, something that powerfully unites us.

Flock of angels lift me somehow

Somewhere high and hard and loud

Somewhere deep into the heart of the crowd

I’m the last man standing now.

This review of Springsteen was lovely and touching. Although I was never a fan of the Boss, I can relate to the feelings you express here. I had felt that for many years for Bob Dylan and The Band. Going to their concerts was intensely spiritual for me--a religious experience that made me feel the oneness of everything. I especially love this part of your review: "is the sense that we are all essentially fragmented from nature and from one another. " OMG, I thought there was something missing from ME! Thank you for sharing your beautiful experience.

TOOM doom.

Why is everybody talking about mortality?

I don't want to die.

I want to deny, deny, deny

The gray monster

Creeping up with finality.

OY!