OUTSIGHT

The Greatest Thing that Never Happened in Psychedelia

Image: everypixel.com

From 1952, neurophilosopher John Smythies sent the eminent English writer Aldous Huxley a number of articles by himself and his colleague, psychiatrist Humphry Osmond (he who coined both “psychedelic” and “hallucinogen”). The articles were on schizophrenia, mescaline, and the mind-matter problem in relation to hyperspatial dimensions. Huxley became fascinated by the exchange, a fascination that led successfully to his book The Doors of Perception and unsuccessfully to a project named Outsight.

Outsight was a bold plan to bring together and give mescaline and/or LSD to fifty to a hundred of the world’s pre-eminent minds, including Einstein, Jung, A. J. Ayer, and Graham Greene. The intention was that “of changing the intellectual climate,” (26 June 1953) as lead instigator Osmond put it to fellow organiser, Huxley. The greater intention was that of changing Western civilisation, away from “the materialist way of life” (ibid.) to one where a transcendental dimension was registered, not by faith but by experience and experiment, not by religion but by science and philosophy.

Unfortunately, Outsight never received the funding it required, and thus never formally happened. Osmond and Huxley put this rejection down to the very intellectual climate that the project was seeking to change: the “stuffy” reductivist academic milieu bewitched to Behaviourism, Freudianism, Mind-Brain Identity theories, alongside other such “arid” materialist ideologies.

In what follows, we shall see the story unfold through Outsight’s origins and intentions, the invited and involved “all-star cast,” its demise or dissipation, and we shall offer a glance at the alternate historical path that psychedelic research and Western civilization might have taken had Outsight succeeded.

John Raymond Smythies (1922–2018) was a British neuroscientist, psychiatrist, and philosopher – or a “neurophilosopher” – who held a number of academic and clinical positions in England, Canada, and the US. Born into immediate luxury in the British Raj in the Himalayan heights of Nainital, India, John, at the age of seven, was switched to the stark austerity of a cold English boarding school. He was related to popular biologist Richard Dawkins, novelist Graham Greene, and the writer Christopher Isherwood, a good friend of Huxley’s – and thus, like Huxley, Smythies was part of an intellectual English extended family.

At Cambridge, where he had become a doctor of medicine at the age of twenty-three, Smythies underwent a deep mystical experience and immediately thereafter he, “without hesitation went to a bookshelf and took down the first book [he] saw. It was Albert Schweitzer’s Civilization and Ethics.” (2005) This mystical experience and the ideas of Schweitzer – a French-German polymath who won the Nobel Prize for his optimistic philosophy of reverencing life and its impulse through multiple disciplines – became the guiding tenets of Smythies’ life. They inspired him to branch out beyond the medical training he had hitherto received, to seek out explanations of life also in philosophy, parapsychology, neuroscience, and more specifically, the study of hallucinations.

Image: the Peyote Cactus, zamnesia.com

These paths in turn led Smythies to explore the psychedelic drug mescaline, traditionally taken via the peyote cactus. Working from 1950 in London’s St George’s Hospital, he speculated that mescaline and schizophrenia may be related in the sense that persons undergoing heavy anxiety may produce an unknown “m-substance”, similar to mescaline, triggering hallucinations. Smythies put this conjecture to his colleague at the hospital, Humphry Osmond, who was taken by the idea. They co-wrote a few papers on this theory, which became globally celebrated as the first neurochemical theory of schizophrenia, and thus one that might eventually lead to a pharmaceutical remedy for the condition. Smythies also sent these papers to Huxley, who was then living in West Hollywood, California, with his wife Maria.

For Smythies, however, who tried mescaline upon himself (publishing an article devoted to the drug’s phenomenology), so-called “hallucinations” (“wanderings in the mind”) were not always of necessity simply delusions. In the articles he and Osmond co-authored, one finds a distaste for concurrent mind-matter theories that reduced consciousness to mere brain activity, or to products of brain activity, or to past or present behaviour. These doctrines of Behaviourism and Freudianism, Psychoanalysis, were at the height of their influence in the mid twentieth century, doctrines which Smythies and Osmond found toxic, as they bewailed:

“An excess of materialism is making a mock of the art of healing … [and] is destroying civilization itself.” (Osmond & Smythies, 1953: “The Present State of Psychological Medicine”)

Smythies had deeper sympathy towards the more Platonic psychological theories of Jung than the more mechanistic ones of Freud (Huxley would irreverently trace the sign of the cross whenever he heard the name, “Freud”), and so Smythies sent his rather radical 1951 paper “The Extension of Mind” to Jung as well – who replied. In the paper, Smythies laid out his theory that we will only understand the mind-matter problem – how “mind” and “matter” relate – now commonly referred to as the Hard Problem of Consciousness, if we increase the number of spatial dimensions beyond the three to which we are accustomed.

Such an increase would incorporate both perceptual space (the sensorium of our minds) and physical space into a more expansive n-dimensional manifold – a sort of Mind-at-Large – with the brain acting as an inhibiting filtering interface rather than as a producer of mind. This latter aspect was akin to the Bergsonian reducing-valve theory that Huxley used to interpret his mescaline experience in The Doors of Perception. As Smythies later put it,

“psychedelic phenomena may represent views of events totally outside ‘ordinary’ space-time.” (1983)

This theory of a twofold space, which Smythies continued to advance throughout his life, was welcomed by Huxley (in his letter dated 25 November 1952), and by Jung, who responded in two letters to Smythies, writing that:

“I welcome unreservedly your idea of the platonic mundus archetypus becoming visualized under the influence of mescaline.” (4 February 1952)

Jung also suggested in his letter the further idea that even time may have more than one dimension, relating it to his concept of “synchronicity” in relation to Leibniz’s harmonia praestabilita. Before Smythies moved to Canada, he visited Jung in Zurich, continuing the consciousness conversation. Smythies stated that “psychedelic phenomena have very little phenomenological relationship to one’s personal memories. Yet one person’s psychedelic world is very like another’s. … Jung [accepted] my suggestion that the psychedelic phenomena originate from the Collective Unconscious.” (1983)

Smythies was on a mission to bring other thinkers into the fold, and so in addition to sending out his articles, he also administered mescaline directly to the Oxford philosopher H. H. Price (see his 1963 essay, ‘A Mescaline Experience’), the Oxford Eastern religious scholar R. C. Zaehner (who later became a critic of Huxley), the Cambridge philosopher C. D. Broad (who also conjectured an n-dimensional solution to consciousness), and to Humphry Osmond himself. In this manner, Smythies had already instigated the Outsight project on a small scale.

Osmond and Smythies moved to Saskatchewan Hospital in Weyburn, Canada, to work in a unit – a mental asylum – occupied by a mass of patients suffering schizophrenia, where they were joined by psychiatrist and biochemist Abram Hoffer. Huxley had posted them his latest book, The Devils of Loudoun: a relevant account of a nunnery plagued by seemingly-demonic possession, and asked for more of their texts on mescaline, a subject and substance that he was already beginning to investigate before Smythies’ first contact (in fact, Huxley had published “A Treatise on Drugs” as early as 1931). These texts became the first references in The Doors of Perception, appearing just after Huxley’s remark therein on Smythies that, “one professional philosopher has taken mescalin for the light it may throw on such unsolved riddles as the place of mind in nature and the relationship between brain and consciousness.”

Image: LSD Tabs, npr.org

On 31 March 1953, Humphry Osmond now replied to Huxley, thanking him for the book. This initiated a decade of correspondence and warm friendship between the two Englishmen, until Huxley’s death in 1963. In this first letter from Osmond, the gestation of what was to become Outsight can be seen:

“some, at least, of our present failure in dealing with the great psychoses arises from our entirely inadequate picture of man. … [There are] great continents of experience, with a stratosphere and a sub oceanic region still untouched. John Smythies and I hope, using biochemical tools such as mescal, [and] lysergic acid [LSD] … to make exploration possible.”

Though a psychiatrist by training, Osmond, like Smythies, realised the importance of fusing science with the humanities and divinities so to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the psychedelic experience. In his 1957 paper, wherein he introduces the word “psychedelic” to the world, Osmond states that: “most important: there are social, philosophical, and religious implications in the discoveries made by means of these agents.” Further, Osmond ends his aforementioned letter by cautioning Huxley not to take mescaline unsupervised, but nonetheless concludes by writing that:

“Having given the necessary gloomy warnings I must add that in my view experiences of this sort, however obtained, are of great value. Body-mind-soul relationships are rarely, among scientists, much discussed now, but I believe that they would become a very lively issue among a group of ex-mescalinized scientists.”

Here we see again that Osmond, as well as Smythies and Huxley, considered the problems of mental health and of civilizational health to be significantly conditioned by the submerged-yet-reigning metaphysics adopted as doctrinal by society. Ideologies rule not merely by religion or politics but by metaphysics, the most pervasive and persuasive of which are those that are not apparent. Thus, by giving great minds mescaline or LSD, the hope was that the underlying “rather arid” materialist metaphysics of society would come to light and be transcended, much like Schweitzer’s call for a rational mysticism for which the necessary experience is a requisite. As Osmond stated: “We now have a chance to use our wonderful technology [mescaline, LSD, etc.] to help us find again some of those things which [our metaphysical climate] has taken away from us.” (26 June 1953)

In his first letter to Huxley, Osmond also mentioned that he was to attend an American Psychiatric Association conference two months thence in Los Angeles, and wondered if he and Huxley might meet. Huxley replied that he and his wife Maria would happily host Osmond at his nearby home, and asked whether Osmond would mind bringing some mescaline with him. Osmond gave Huxley the mescaline – “four-tenths of a gramme … dissolved in half a glass of water” – on the morning of May the 4th, 1953. The report and interpretation of that experience became legendary: the 1954 book, The Doors of Perception.

Later in the month, Osmond writes back to Huxley, now formalising the Outsight project further:

“Our Number One project is the one which I outlined to you in Los Angeles – a series of recorded mescalin interviews with 50–100 really intelligent people on various professions and occupations. We might use lysergic acid [LSD] too. Our object would be to explore the transformation of the ‘outer’ world and the revelation of the ‘inner’ world which occurs. It is evident that until this has been experienced it is largely meaningless, but once it has been experienced it is unforgettable. Most of us experience the transcendental so rarely and so fleetingly that we doubt whether it ‘really’ is there or not. The mescal and similar experiences removes this doubt. I don’t think it is possible to discuss psychology seriously without taking these extraordinary experiences into account. There is nothing very new in our idea – William James had much the same hunch many years ago.” (25 May 1953)

The first phase of Outsight concerned the formation of an organisational board. The second, to invite and administer the psychedelics to the great minds. The third phase was to create symposia for them to discuss their experiences together. The fourth phase would be the hope of disseminating the new insights:

“If we can build up a group of gifted people who have had transcendental experiences and then get them together, I think that there is a reasonable chance that they might find some way of passing on this experience and giving some chance to those who only have vague inklings of it or the splendor and terror that exist just around the corner. So far as I know nothing like this would ever have happened in the West before – the drawing together of gifted people who have had astonishing experiences.” (Osmond to Huxley, 26 June 1953)

Actually, something somewhat like this had happened in the West before: the Parisian Club des Hashischins of 1844–1849. This was a group of gifted figures who met to take and meditate upon hashish and other psychoactive substances. Members included Charles Baudelaire, Jacques-Joseph Moreau, Théophile Gautier, Alexandre Dumas, Gérard de Nerval, Eugène Delacroix, with occasional visits from Honoré de Balzac, Gustave Flaubert, and Victor Hugo. Osmond did later read Baudelaire’s 1860 classic hash and opium tome, Les Paradis Artificiels, finding it “very interesting but disappointing” (5 September 1955). Of course, Outsight would have included many more minds than the Parisian club, with more potent substances allowing for, one would imagine, more potent psychonautical explorations.

The aim was to unfold deep insights outwards, thus the name, “Outsight.” Who were these proposed fifty-to-a-hundred elect outsighters? The all-star cast who were explicitly being considered included the following:

Albert Einstein (German theoretical physicist)

Carl Jung (Swiss psychologist)

Graham Greene (British novelist)

Albert Schweitzer (German-French polymath)

Heinrich Klüver (German-American psychologist)

D. T. Suzuki (Japanese philosopher)

A. J. Ayer (British philosopher)

C. D. Broad (British philosopher)

Gilbert Ryle (British philosopher)

H. H. Price (British philosopher)

Gerald Heard (British historian, mystic)

Eileen Garrett (Irish parapsychologist and medium)

J. C. Ducasse (French-born American philosopher)

Gardner Murphy (American psychologist)

Nolan D. C. Lewis (American psychiatrist)

William H. Sheldon (American psychologist)

Alfred Matthew Hubbard (American businessman)

Christopher Mayhew (Labour and Liberal MP)

And the founders:

John Smythies (British neurophilosopher)

Humphry Osmond (British psychiatrist)

Abram Hoffer (Canadian biochemist and psychiatrist)

Aldous Huxley (British writer and philosopher)

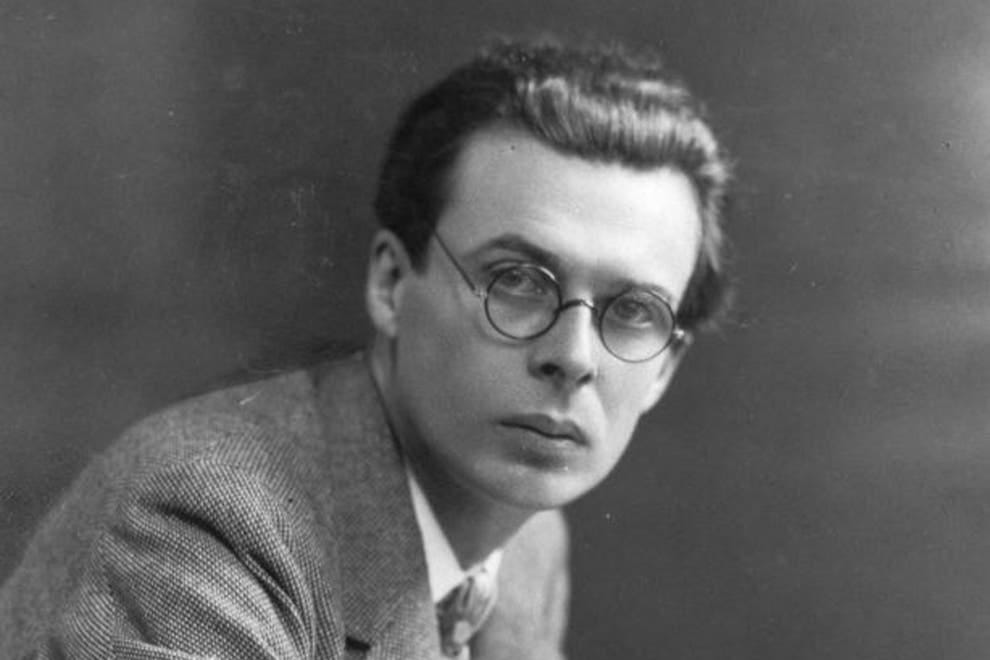

Image: Aldous Huxley, independent.co.uk

This is a fine selection considering it was the mid-1950s. I personally would have also included – considering their relevant interests in the mind and cosmos – quantum physicists Werner Heisenberg and Erwin Schrödinger (who both wrote on physics and consciousness in the 1950s), David Bohm, Albert Hofmann (the chemist who synthesised LSD), his friend German-philosopher Ernst Jünger (who had already written about the LSD experience in his 1952 novella Visit to Godenholm), Kurt Gödel (the incompleteness logician strolling Princeton with Einstein, interested especially in Leibniz and Husserl), Martin Heidegger, Hannah Arendt, J. R. R. Tolkien, Jean-Paul Sartre (who had already taken mescaline as is widely documented), Mary Midgely, a young Timothy Sprigge (the absolute idealist), Isaiah Berlin (considering his penchant for Romanticism), Herbert Marcuse (who did allude to the political aesthetics of psychedelics), and Bertrand Russell (Huxley’s philosopher friend, “Bertie”). I doubt many would have accepted the invitation, but H. H. Price was particularly keen, and A. J. Ayer did write about a psychedelic-like cosmic life-changing experience he underwent after choking on salmon whilst suffering pneumonia.

Of course it would be somewhat costly to pay for these outsighters to travel and stay in Saskatchewan, to pay the supervising psychiatrists, the labs, to pay for the organising committee to meet in, as was proposed, New York, and so on – yet the estimated cost of around $40,000 (almost $500,000 in today’s money) for the first two years seemed relatively inexpensive to Osmond. But where would they find such initial funds? In LA, Huxley would host parties at his home every Tuesday evening. Many interesting and influential figures would be invited, one of whom was the American educational philosopher Robert Maynard Hutchins, president of the University of Chicago and, importantly here, an officer for the Ford Foundation.

Osmond had placed much hope on securing Outsight funding from this institution, but unfortunately, it never materialized. Osmond realised that the Ford Foundation committee consisted of numerous “stuffy psychologists” (26 June 1953), safely wedded to the reductive paradigms of the day, the very paradigms Osmond and his “Pickwickian organisation” (as Huxley later called it) sought to alter. Osmond even suggested (26 June 1953) giving Hutchins a dose of mescaline to heighten their chances. But a few months later, Huxley reports back that the “mesozoic reptiles of the Ford Foundation are being as mesozoic as ever” (25 September 1953). Osmond immediately replied: “What witlings they are! Of course if they want to have any chance of backing good research they must back the queer and unlikely, for what is about to be discovered must of necessity be unlikely.” (26 September 1953).

If our Englishmen had requested funds for a militant rather than philosophic project, they may have encountered success. In the very same year in which Outsight was being planned, the CIA was launching Project MK-ULTRA to determine whether LSD could be used for mind control and acts of violence. As part of this shadowy programme, the CIA was to spend $240,000 (almost £3million today) alone on the purchase of LSD, ten kilograms, the total supply from Sandoz Labs in Basel, Switzerland, in that seminal year of 1953. Moreover, the CIA later used the Ford Foundation to channel funds for cultural interference. Perhaps it was ultimately fortunate that Osmond and all did not fall into Ford’s lap.

Regardless, Osmond had hoped for funding from elsewhere, saying that Smythies had identified new possibilities, but the interest or motivation was never to be found. Considered generally, it does seem rather unfortunate that the psychedelic revival of the mid twentieth century coincided with the most reductivist period in academic and official Western history, where even the concept “consciousness” was frowned upon. Or, from another angle, perhaps the psychedelic revival was the inevitable immune response for that period, the necessary pressure-relief of a physicalist ideology that had become too constricting.

There were further, more specific causes that had begun to emaciate the momentum of the Outsight project. Smythies had become sceptical of the very mescaline-based transmethylation theory of schizophrenia that he himself had originated, and had left Osmond in Saskatchewan in late 1953. Moreover, Osmond had become increasingly hostile to Smythies thereafter, as one can see in the Osmond–Huxley correspondence.

Smythies had really originated Outsight as well, and was on the proposed board of the organisation, organising invitees, etc., as we see in many of Osmond’s letters, but decades later Smythies himself told me – in private correspondence – rather surprisingly that, “I was not involved in the Outsight Project if by that term you mean the approach to the Ford Foundation made by Osmond, Hoffer and Huxley.” (28 November 2018). Smythies went on to work elsewhere on mescaline as well as on strobe lighting effects on consciousness, all under the purviews of psychiatry, neuroscience, and the philosophy of mind. He taught at the Universities of Edinburgh, Alabama, and at the University of California, San Diego – never letting go of his obsessions with altered states and n-dimensional consciousness. He died in January 2019.

Rewinding back to the 1950s, the team had broken with Smythies, and seething resentments seemed to have lingered. Another reason for the deceleration of Outsight was the death of Maria Huxley, who succumbed to cancer, passing in February 1955. This death had, however, sparked the idea in Aldous’ mind of using psychedelics as part of end-of-life care. Indeed, Aldous Huxley himself was given a dose of LSD on his deathbed, transitioning himself through to, perhaps, the extra-dimensional. He died high on 22 November 1963: the day J. F. Kennedy and C. S. Lewis also passed away.

But the Outsight project, broadly speaking in terms of its intentions, did not really die but rather disseminated: it lived on through the vast outward influence that the insights bequeathed to Huxley by mescaline had on the world through his book The Doors of Perception and its sequel Heaven and Hell, and through his last novel Island with its psychedelic “moksha medicine.” Moreover, the potentiality of psychedelics to enhance humanity lived on as an aspect of the human potential movement that Huxley later advanced, leaving behind a legacy of thought and institutions such as Esalen.

Allene Symons’ 2015 Aldous Huxley’s Hands, a fascinating book on her father Howard Thrasher’s work on relations between hands and personalities, made me aware of the Outsight project. Her father was a regular visitor to Huxley’s Tuesday sessions. In the book, she speculates about what course history may have taken had the Outsight project been funded and activated:

“A high-profile Outsight gathering in 1955 might have ushered in well-funded studies, and that might have changed the plans five years later of a young professor [Timothy Leary] who came to Harvard and sent psychedelic research off the rails.” (p. 175).

Huxley, Osmond, and Smythies were very concerned about the direction that Leary was steering psychedelic research and publicity. Huxley had corresponded with him and met him in person, saying “he talked such nonsense” (26 December 1962). Osmond was harsher, worrying about Leary’s competence, his ego, his malpractice, safety concerns, and unsophisticated theories of consciousness. All three Englishmen were worried that Leary’s popular advocacy of psychedelics would halt serious psychedelic research, which bore some truth: President Nixon, who launched the “War on Drugs” in 1971, called Leary “the most dangerous man in America” (no doubt a badge of honor for Leary).

Certainly Leary played a flaring role in the prohibition of psychedelics, yet the underlying conditions of this symptomatic prohibition, conditions that inhibited the advocacy of Outsight, are deeply rooted in histories of metaphysics, heresy, and cultural politics, considering the earlier drug prohibitions of the conquistadors, the temperance movement, the twentieth-century post-war prohibitions in Berlin, to name but a few precursors. Nonetheless, the Outsight project might have made a mark in making a move beyond certain such historical legacies, ushering in a post-1950s respect and revenue for psychedelic research and multi-dimensional mystical mind-matter endeavours, thereby potentially inaugurating a shift away from what Schweitzer called, “the tragedy of the Western world-view,” and thus heeding his call:

“The way to true mysticism leads up through rational thought to deep experience of the world … . We must all venture once more to be ‘thinkers,’ so as to reach mysticism, which is the only direct and the only profound world-view.” (Civilization and Ethics, 1923)

– – –

[I should like to thank Drs. Robert Dickins, Matthew Segall, John Buchanan, and Andrew Davis for reading a draft of this essay and offering helpful suggestions.]

Fantastic review of what might have been had the psychedelic river changed course.

What Leary did was very dangerous because he was advocating LSD use to random people, without considering how the drug might affect them. Nonmilitary, serious research with carefully selected individuals could have yielded knowledge about psychedelics. I never took anything stronger than hashish or poppers because I felt there was a lot in my mind that I was not ready to just let loose. Too much traumata that might give me an ugly trip. Yet, I've had my own "psychedelic" types of experiences, including the dissolution of ego at concerts, the blazing expanding geometrics of silent migraines, and experiences from strong marijuana and loading doses of gabapentin. I like having my consciousness raised slowly as I can deal with each layer safely as the revelations occur. To me, the physical world can be extremely colorful and beautiful and I always visualize things from what I read or from songs I hear. What I visualize is very vivid. I am contented with this.