My Father’s House

Springsteen, Deliver Me From Nowhere

Image: flickriver.com

I told her my story, and who I’d come for

She said, “I’m sorry son but no one by that name lives here anymore.”

Bruce Springsteen, “My Father’s House”

Excitement for the Film and the Enduring Power of Nebraska

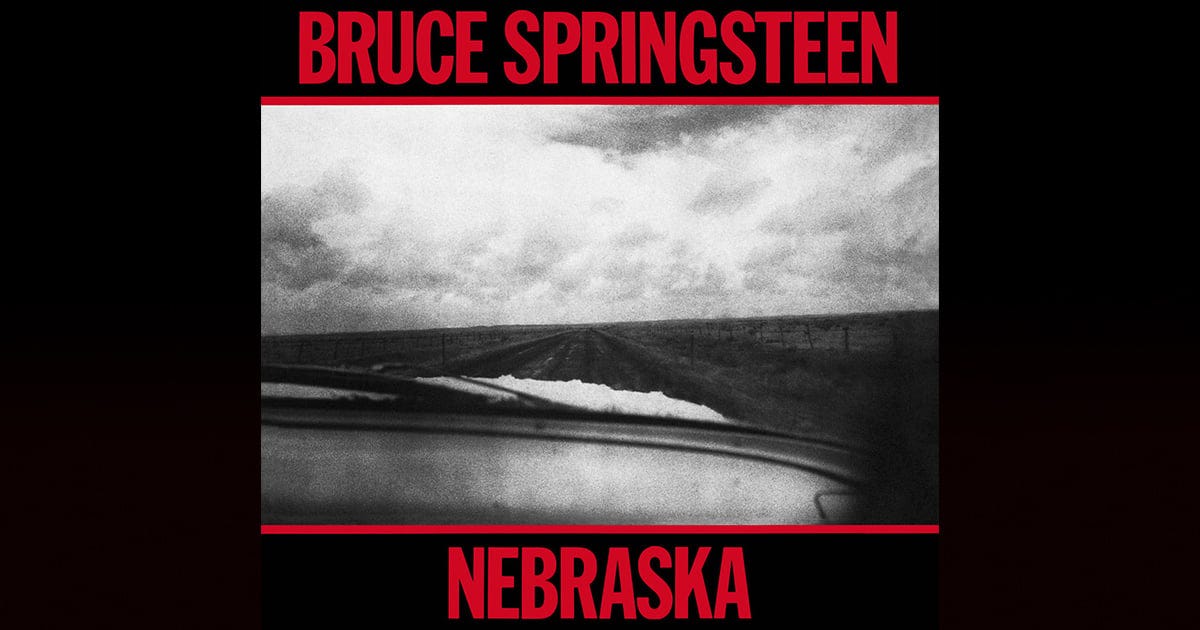

To say that I was excited when I learned that a biopic on Bruce Springsteen was in the works, with the legendary singer to be played by Jeremy Allen White (of Shameless and The Bear fame), would be a gross understatement. But my reaction to the further discovery that the film would focus on the recording and production of Springsteen’s 1982 masterpiece, Nebraska, was nothing short of ecstatic. In what follows, I offer not a review of the film, so much as a personal and philosophical reflection on the way it affected me, on its power to reach us in the “nowhere” that we all occupy at various stages in our lives.

Nebraska, the raw, acoustic “demo” album, famously laid down on a four-track recorder in the bedroom of Springsteen’s rented New Jersey home, his first album without the accompaniment of the E Street Band, has long been my favorite entry in the Boss’s extensive discography. Bookended by the grandeur of 1980’s The River and the anthemic glory of 1984’s Born in the U.S.A., Nebraska stands apart for its simplified sound, its vivid storytelling, its unflinchingly honest explorations of blue-collar despair, and its technical imprecision, all of which lend themselves to an exceptionally visceral authenticity. Moreover, its release amid the polished, futuristic, synth-driven bombast of pop music in the early MTV era only amplifies its iconoclastic status.

The album opens with the title song, inspired by Terrence Malick’s directorial debut, Badlands, about the 1957-58 killing spree of Charles Starkweather. Other tracks include “Atlantic City,” with a desperate couple fleeing for the eponymous town, where the man hopes to find work in organized crime; “Johnny 99,” about a car factory employee who loses his job, kills a night clerk, and is sentenced to ninety-nine years in prison; “Highway Patrolman,” whose title character Joe has to constantly come to the aid of his outlaw younger brother, Frankie, who eventually injures (presumably fatally) a man in a bar fight; and “Mansion on the Hill” and “Used Cars,” about the youthful yearning, familiar to those of us who grew up in blue-collar America, for a better life.

And while earlier albums had contained tracks that spoke to working-class despair and criminal desperation (such as “Meeting Across the River” on Born to Run, “Factory” on Darkness on the Edge of Town, or the title song on The River), there is a unique blend of specificity and universality across the whole of Nebraska that effectively captures the disillusioned climate of the post-Vietnam United States in the late 1970s and early 80s, amidst the related phenomena of deindustrialization, high inflation, and rising unemployment. “They want to know why I did what I did / Well, sir, I guess there’s just a meanness in this world.” With Nebraska, Springsteen’s craft skyrockets into the domain of American myth.

An Unlikely Choice: The Album’s Obscurity and the Film’s Deeper Layers

Image: brucespringsteen.net

Nonetheless, given that the album yielded only two singles (neither of which was released in the U.S.), was followed by no publicity or interviews, was accompanied by no tour, and is relatively unrecognizable to most casual fans, Nebraska may seem an unlikely selection for the focus of a biopic. This likely explains, at least somewhat, the general collective shrug at the film on the part of many critics. In The Spectator, Deborah Ross writes that the film “will doubtless satisfy the completists. But non-completists – I could have named only two of his songs, tops – may wonder if it’s that interesting.”

And while I generally find criticisms of the sort, this film will only be interesting to people who are interested in the subject matter of the film; to be lazy and uninformative, there is, nevertheless, an element of truth in her characterization. Specifically, the film is every bit as much a biography of the album as it is a memoir of the artist, and given the album’s relative obscurity compared to Born to Run or Born in the U.S.A., it stands to reason that there are likely layers to the film that will be inaccessible to casual viewers (though, to be clear, there is plenty of substance throughout the film to hold one’s attention, including a rare and welcome exploration of clinical depression).

Knowing something of the album’s backstory, I went into the film expecting a narrative about artistic integrity, about the tensions between the vision of the musician and the commercial demands of mass-marketed entertainment, and about this period of Springsteen’s life. The film certainly is all of these things, but it is much more.

Thresholds and Nowhere: Liminal Spaces in Life and Art

What I did not expect from the film was the concentrated reflection on the reckoning that overtakes us all at various moments of passage and metamorphosis throughout our lives. The film’s subtitle, Deliver Me From Nowhere, refers to a poignant line that appears in two songs on the album, “State Trooper” and “Open All Night,” both of which focus on the nebulous disorientation of a late-night highway drive, in the small hours when the world is muted in every sense, when the landscape and the horizon are imperceptible, and all that exists before us is the road: “Radio’s jammed up with gospel stations / Lost souls callin’ long distance salvation / Hey, Mr. DJ, won’t you hear my last prayer? / Hey ho, rock ‘n’ roll, deliver me from nowhere.”

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere is a story about the thresholds of our being. A threshold is, itself, a “nowhere,” a liminal space, an interstice of time, a moment of terrifying transition, wherein we recognize that what has been is truly and irrevocably gone, and what comes next is wholly unforeseeable. Such thresholds are often accompanied by profound interrogation of the meaning of that history, how it has determined us, and what it implies for a future which, in that moment, is but an anxiety-colored haze.

Springsteen’s own description of Nebraska is that it was born of the overwhelming commercial success of 1980’s The River, and expresses a deep sense of struggle and guilt over the realization that he was leaving behind the life and the community that had fostered him, in exchange for what would soon be stratospheric superstardom, (with Born in the U.S.A., written and recorded at the same time, right around the corner). This aspect is conveyed, subtly but powerfully, throughout the film.

One of the more prominent (and, for me, unexpected) thresholds in the film is Springsteen’s confrontation with the tortured relationship with his father, an emotionally abusive alcoholic struggling with severe and undiagnosed mental health issues, whose behavior towards the young Bruce could range from affection to terrifying manipulation.

From childhood, Springsteen is portrayed as having to bear a responsibility far beyond his years for the people whose job it was to care for him, in flashbacks such as his mother sending him into the bar one afternoon to retrieve his father, or young Bruce intervening with a baseball bat to protect his mother from his father, (an act that his father ultimately praises, for a boy, he says, should never let anyone hurt their mother). Those of us raised through the fog of a substance-abusing parent know this story and its vacillations well, along with the unmooring of emotional identity that comes with it.

But this specific biographical framework offers a broader reflection on the moments of life when we reckon with the meaning of childhood itself, and on how we carry it with us even as we leave it behind. My favorite track on the Nebraska album has always been “My Father’s House,” a meditation on the theme of home, on the ways it both nurtures and scars us, casts us out, and beckons to us. The song begins, “Last night I dreamed that I was a child / Out where the pines grow wild and tall / I was trying to make it home through the forest / Before the darkness falls.”

As night descends, the frightened boy races to the house and falls into the comfort of his father’s arms. But this is but a dream of a grown man, and the song vividly narrates awakening from this dream and returning to the house in pursuit of a reconciliation with his father, only to find it inhabited by a stranger. Deliver Me From Nowhere brings the spirit of this song powerfully to life, and it jarred me with extreme emotional intensity as someone who, having recently seen his two children into adulthood, now finds himself wrestling with his own parenting failures and struggling to better understand his own father. The film reached me in my own “nowhere,” speaking to something profoundly personal, hearkening back to a recent encounter.

My Father’s House: A Personal Reckoning

Image, realtor.com

This past summer, my fiancé and I traveled from Pennsylvania for a brief visit with my family in Illinois. We exited Interstate 70 in the small town of Greenup, which is but a short drive from Hidalgo, the village of about one hundred people where my father lived most of his life. We had reached the exit much earlier than anticipated, with daylight still to burn, so we decided to drive out of our way for a brief view of the town where I had spent my weekends with my dad. I believe it was the first time I’d been through the town since before my father died.

I drove her down the single through road in town, past the home where my grandparents used to live, past what used to be Bob’s Hardware, past the post office and what used to be the town grocery store, past what used to be the grain elevator, adjacent to what used to be railroad tracks, past the municipal building, before driving her to the edge of the forest where my brothers and I passed many a wintry Saturday. We ultimately came to rest at one of the crucial loci of my childhood, the parking lot of the church where I grew up and was baptized, positioned directly across the road from my father’s house.

I pointed out the church parsonage that I helped build as a teenager, the yard where my brothers and I played pitch and catch and where I caught a pitch to the face that dislocated my jaw (an injury that still ails me from time to time), the barren spot behind the house that once held a chicken coop (which served perfectly as a hideout for my brothers and me), the tower antenna that brought us our few television channels, the gravel driveway, now overgrown, where my dad had repaired my first car, the silver propane tank which functioned for us as a makeshift ladder into a tree (once holding a tire swing) that no longer exists, the upstairs window to what had been our toy room, etc.

At the center of it all was my father’s house, standing uninhabited since spring 2020, when my father and stepmother moved to the country. The spectral atmosphere of the town and the dark stillness of the home were the perfect metaphors for the ghost of my father that has haunted me since I lost him almost five years ago. As most are, my relationship with my father was complicated. My parents separated just after my first birthday, and before I was old enough to begin forming memories and self-awareness, my father had fathered two more children.

Given his demanding work schedule and the fact that he lived forty-five minutes away from my mom, my visits were limited to every other weekend, and as his family grew and the activity of the family with it, so too did the sense that my bimonthly visits were something of an intrusion into a household that typically operated entirely without me. I was a guest, an outsider, and it brought with it a great deal of loneliness. I have no doubt that I carried bitterness from this estrangement well into adulthood.

But my dad’s love for me was undeniable. It was steady, reliable, and unwavering. He was present for every basketball game and every band performance and parade that he possibly could be, even when they fell on a Saturday morning after a twelve-hour night shift. He bought me my first car and helped me repair it as needed. He attended every one of my college graduations, and proudly came to hear me speak when my alma mater, the Philosophy department at Eastern Illinois University, invited me back. He used his vacation days to help me whenever I moved. He once gave up a weekend to drive three hours to help me build a fence, and I could recount dozens of such stories.

But the times I felt most loved were bedtimes as a child. My brothers and I typically slept in a single bedroom just off the living room. My dad and stepmom would often stay up beyond our bedtime to watch television. Every night, without fail, before my dad would retire, he would come to tuck us in. And though there were four of us and he was almost certainly exhausted, he took great care with it. He would make sure we were covered snugly, tuck our blankets under our bodies, then he would stand and look at our faces, maybe brush the hair from them, before kissing us on the forehead, whispering ‘I love you,’ and moving on to the next. I would sometimes feign sleep, as I never felt safer or more loved than I did in those moments of total vulnerability when, with no expectation of reciprocity, my dad would patiently abide in his love for me.

I’m grateful that we never lost touch, even as life and our relationship became increasingly complicated. There were Sunday night phone calls that went on for hours; annual kayak trips; texting play-by-play commentary while watching a football game together (seven hundred miles apart); milkshakes and fries at Steak ‘n’ Shake. But there were also countless little wounds and ruptures lingering between us over the years that I never addressed. As my children approached adulthood, I assumed that one day I would have the chance to sit down with my dad, just the two of us, and work through it all, hoping that I might really get to know him for the first time. He died, unexpectedly, in January 2021.

It has often struck me as ironic that everything I’ve learned about what it means to be a man, I’ve learned from a man I rarely saw and, in many ways, felt like I didn’t know. As my own children have entered adulthood, I have increasingly grappled with the realization of all the ways I’ve failed as a father, and my own struggles to forgive myself and make peace with those failures are in many ways a reflection of my struggle to reconcile with the ghost of my father.

This struggle overtook me as I sat in the “nowhere” this past summer, staring at my father’s house, in that uncanny juxtaposition of the strange and the familiar, the living and the dead. “I walked up the steps and stood on the porch / A woman I didn’t recognize came and spoke to me through a chained door / I told her my story and who I’d come for / She said, ‘I’m sorry, son, but no one by that name lives here anymore.’”

While this story is different from yours or anyone else’s, there is nothing special about it. We’ve all got untended wounds, scars, and ruptures. We all pass through these thresholds; we all find ourselves in the “nowhere,” and every one of us is haunted by ghosts. But that is precisely what made my experience of Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere so powerful, that through a vulnerable portrayal of the most painful details of Springsteen’s past, the film tapped into something universal about the human experience, jarring me in ways and awakening reflections in me I could not have anticipated.

It lays bare the ways in which time can both break and heal us. It confronts us with the question of how to forgive, how to reconcile oneself with the specters of a past one can neither regain nor correct. It touches the desolation within us that cries into the night to deliver us from nowhere. And it speaks to the ways we both hurt from and long for home.

My father’s house shines hard and bright

It stands like a beacon calling me in the night

Calling and calling, so cold and alone

Shining ‘cross this dark highway where our sins lie unatoned

Far too many people, having "grown up" out of fandom, do NOT understand how some people can identify strongly with an artist's vision even in adulthood. This is especially true for people whose lives in some fashion were broken by traumata. The sheer lonesomeness of it makes one experience a deep sense of wonder when an admired artist expresses a similar trauma. Been there, done that, and still can't really talk about it.