Music for Jung People

The Collective Conscious and the Grateful Dead.

Image: The Acid Test, recordmecca.com

When Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters staged the Acid Tests, it became clear in those early days that the people around you affected the trip. Trying to make sense of this relation between other people and one’s own conscious experience led to the psychology of Carl Jung. The house band for the Acid Tests would eventually take on the name the Grateful Dead and Jung’s influence would remain with them, indeed to this very day as a decedent of that original band performs in the Sphere in Las Vegas.

The Collective Subconscious

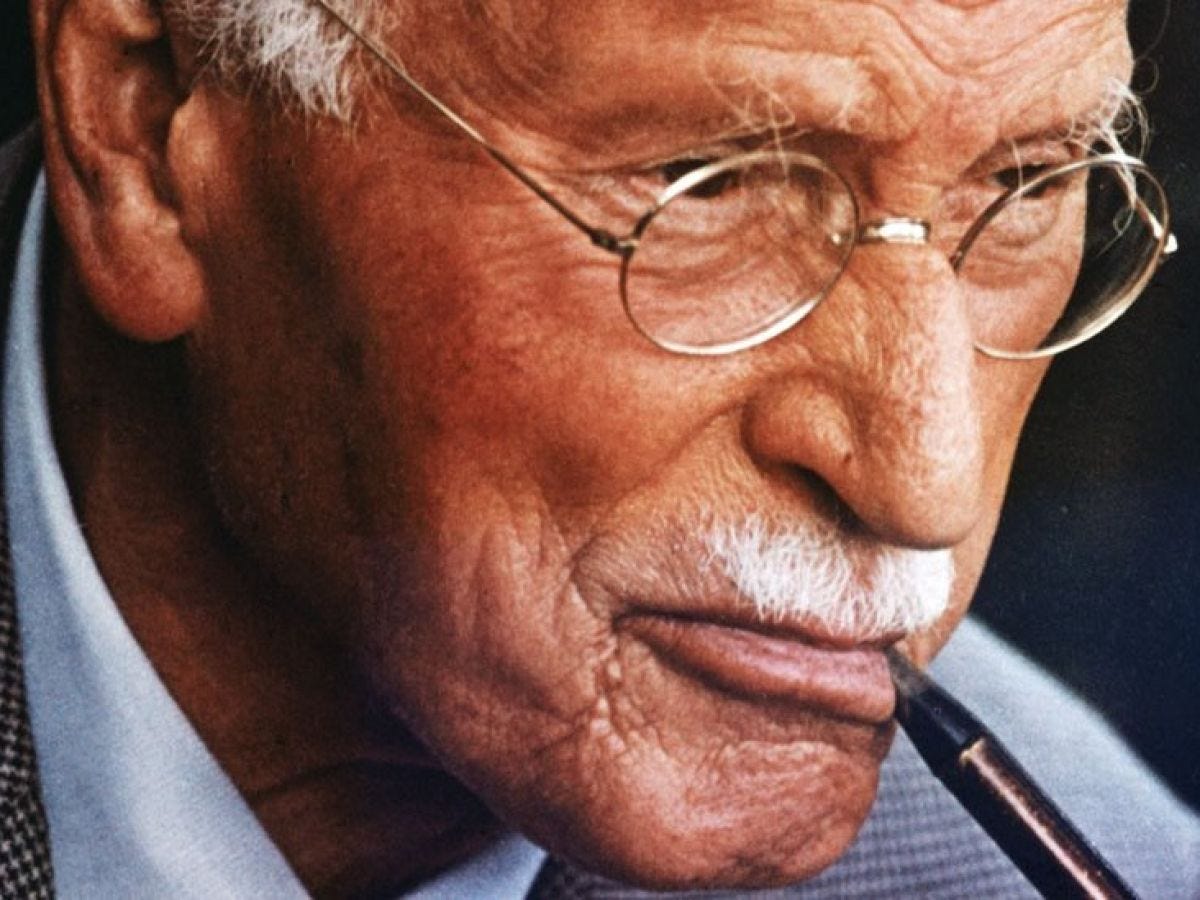

Carl Jung was a disciple of Sigmund Freud. Indeed, he took over as head of the Psychoanalytic Society after Freud’s passing although there were important differences between their views of the human mind. Freud had been trained as a medical doctor and worked in a lab dissecting crawfish to examine their nervous systems. He began with a materialist picture in which to understand consciousness, you looked at the brain.

This changed when he went to France and studied with Jean-Martin Charcot who was experimenting with the use of hypnotism as a treatment for hysteria. Watching Charcot work, Freud began to believe that the root cause of some mental illnesses may be buried inside the human psyche, invisible scars left over from earlier experiences. Instead of the brain as a physical thing, he began to see the object of study in psychiatry as the non-material mind which had a conscious element that he called the ego which is Latin for “self” because it is the part of the mind we have direct access to and control over.

But then he posited two subconscious elements that operate on us while remaining unseen by the self. The id is the repository of basic urges and desires. Freud was thinking in the shadow of Charles Darwin and this was the residue of our pre-human past, the animal part of us. But then there is the super-ego, the conscience, which is the result of socialization by our parents and the broader culture. It contains the social expectations that we internalize.

Freud was hostile to religion, seeing it as a leftover from a juvenile state of human society and which is capable of warping the mind in irrational ways that can lead to neuroses. Jung was the lone Christian in Freud’s circle and had a spiritual bearing that led him to look at religion in a different light. Religious stories, myths from cultures that were widely separated in space and time, Jung noticed, eerily resembled each other. Societies that had no contact and could not have influenced each other still shared characters, events, and narratives that were shockingly similar. This, he thought, was a phenomenon that required explanation.

Jung framed a novel hypothesis. For Freud, minds were atomic, each person has their own and each is self-contained, but Jung wondered if that might be wrong. Maybe the part of the mind below the level of consciousness is shared. Maybe we all partake in some way of the same subconscious, the collective unconscious. In some places in his writing, Jung takes a more Freudian picture that we all have individual minds, but that one part of the subconscious starts off the same, that all members of the human race inherit the same underlying component in our individual minds.

But in other places, he paints humanity as a united tapestry of interconnected minds. We are not atomistic individuals, but rather parts of an interwoven spiritual web, nodes on a single coherent network. Jung thought that this would explain the commonalities in mythologies and the occurrences of synchronicities, strange happenings that seem to bring us and the universe together in uncanny ways that seem too perfect to have been merely random.

Breaking Down the Wall

Image: Karl Jung, radio.perfil.com

When groups began experimenting with psychedelic substances in the 1960s—Harvard Psychologist Timothy Leary led one group on the East Coast and Kesey had his group on the West Coast—Jung’s ideas were discussed as explanations for the experiences. Those who partook almost universally experienced a sense of interconnection, of oneness with others and all things, and small events that seem to be instances of synchronicities took on great importance. Jung seemed a natural fit to explain the trip.

Kesey’s Acid Tests were furnished not only with LSD added to Kool-Aid, but also light shows, tape loops and microphones that altered sounds, and other unusual props that might make appearances during the event in unexpected ways. There was no predetermined choreography of the evening, the experience was to unfold organically, but accoutrement that might elevate the event were provided. Part of that was a band that partook in the reverie and could play or not depending upon what felt right at the moment. Nothing would be forced, but whatever would happen would be allowed to happen no matter how strange.

Phrases like “expand your consciousness” began to be used and the question was whether the odd effects which came with a deep sense of meaning to those who experienced them were telling us something profound about consciousness itself. Maybe Jung is right and what was happening in this altered state of consciousness is that the subconscious is being exposed to us. We are getting to see a part of our mind that is usually hidden and maybe that part is connected to everyone else’s minds.

Fingers on a Hand

This experience of interconnectedness became the core musical philosophy of the Grateful Dead. Perhaps the act of performing itself is a path to that interconnection. Blues and jazz musicians had long improvised and the Grateful Dead noticed that there would be transcendent moments in their own playing where the band itself spontaneously composed something wonderful. This new music came from the players, but no one individual had thought it up, no one person had consciously composed it. It emerged from the group mind, not from any particular individual mind.

They discussed this and decided that their goal in playing was a “mind meld,” pulling a term from Star Trek that was all the rage at the time. Another way they expressed it was that they wanted to be like “fingers on a hand.” Yes, you have different fingers—one might point while another insults—but they work in unison as a coherent whole as you pick things up or type out words. They would seek to lose themselves as individuals in order to connect their souls for the sake of the performance.

As a result, their musical approach sought open space to allow the song to develop as it would. Each performance differed from every other because this was the one that came out of the organics of the world from which it emerged. The set list and the playing itself would be allowed to reflect the world as it created it.

The psychology that influenced the musical philosophy caught the ear of psychologists. Dr. Stanley Krippner has a Ph.D. from Northwestern University and was a professor in Oakland as the Grateful Dead was establishing itself across the bay. He introduced himself to them and a mutual relationship began.

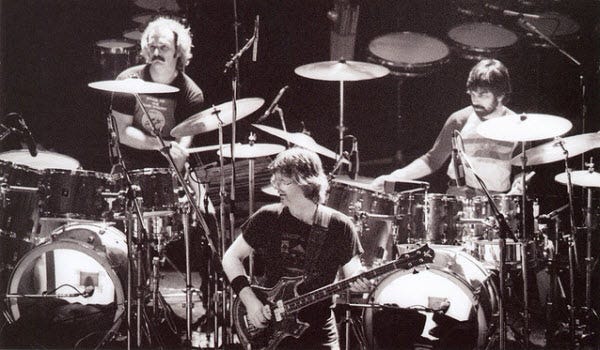

Image: Bill Kreutzmann, Mickey Hart, and Phil Lesh of the Grateful Dead, woodstock.com

Billy Kreutzmann and Mickey Hart, the band’s two drummers would have hypnosis sessions together with Krippner seeking to be able to play as if they were one drummer with four hands. And Krippner, in the other direction, would run experiments to see if there were detectable effects in the minds of audience members during the show from the collective creative experience. Could there be ways to detect the effects of Jung’s collective unconsciousness?

The Dead understood the audience was a necessary part of this connection. When interviewed for the book The Grateful Dead and Philosophy: Getting High-Minded about Love and Haight, one of the band’s guitar players, Bob Weir, explained that the source of the music was what he termed “the azimuth.” He said that the musicians were on stage, while the gathering members of the audience were in the seats or on the floor of the auditorium, and between them was a space.

They face each other across a gap, and that gap is what Weir calls the azimuth. In it was the location of the interplay of the two sets of minds in that space that produced the energy guiding that night’s performance. Sometimes the crowd was more laid back, other times more revved up and the band’s performance would reflect the audience’s mood, all the while the audience would react to the band, creating a feedback loop that expressed itself through the energy emerging from the azimuth.

This concept would form the philosophical heart of the jam band movement which thrives still, not only with bands influenced by the Grateful Dead but with Weir and Hart and the rest of Dead and Co. as they continue to meld minds and explore the symbiosis that occurs in the azimuth, the Jungian space where creative energy is formed.