Mind Control

Mental causation and evolution.

INTRO

A conflict of questions: To what extent, if any, does the mind exert control? It seems to many if not most of us that our mind can control parts of our body, and that it can control parts of itself. Does it not seem that my desire for tea can cause, at least partly, my finger switching on the kettle? Does it not seem that my thought of the ocean can cause, at least partly, my next thought: sea life? But does it not also seem that everything that happens in nature only happens according to the laws and forces discovered and prescribed by physics (a view known as physical determinism)—laws and forces that exclude such mind control, or mental causation? The mind itself is not a known force of nature and seems to abide by no known law of nature.

So do we not operate according to the same forces and laws by which billiard balls and orbiting planets operate? How could mentality escape from this general framework of reality? How could mind operate in a physical universe? This is the picture from physics; but, as we shall see, this picture conflicts with the picture from evolution: If mentality had no power, why would it have evolved and maintained existence amongst presumably myriad species? Let us enter this mental matter to get a better picture.

WHAT IS MENTAL CAUSATION?

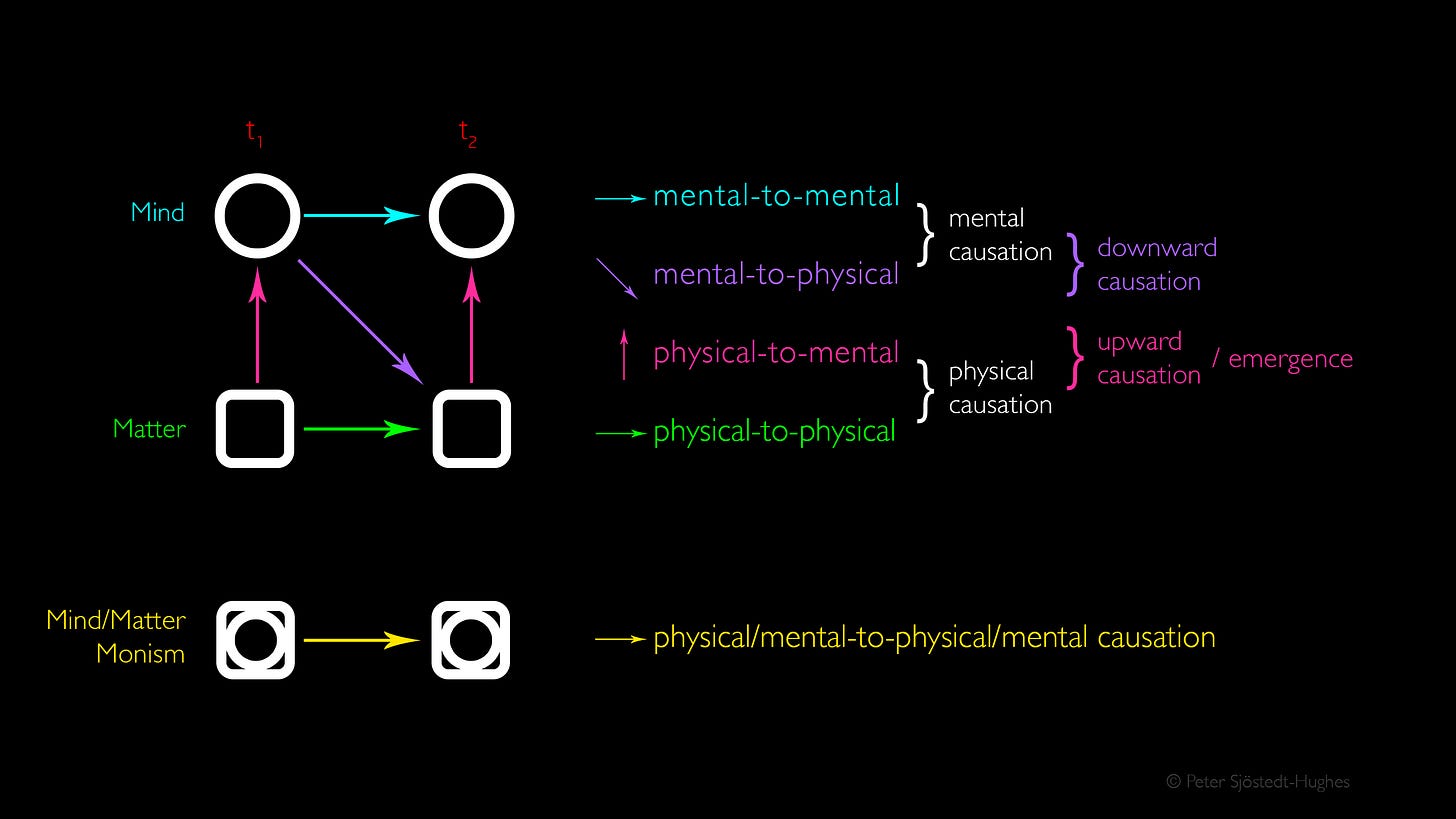

One can distinguish, firstly, mental-to-physical from mental-to-mental causation: as in the above examples, respectively, of the tea-desire-to-kettle-switching and of the ocean-thought-to-sea-life-thought. One can, secondly, distinguish determined from free mental causation: psychological determinism and psychological freedom. The second is what is generally called “free will.” Consequently, one can believe in mental causation without believing in free will—they are not the same. (With regard to the prior question as to how we understand mind, mentality, consciousness, or sentience, which I use synonymously in this text, see here, and see the proposed examples of mental causation below.)

Psychological Determinism

Contrary to physical determinism lies psychological determinism, the view that one’s body and mind are not merely determined by physical causes but by psychological ones too. This is more or less the view of the idealist philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer. He argued that mentality can play the role of offering a menu of possible actions in the imagination, but that the possibility of action taken was determined by the Will—and the imagination had no power over the Will.

This is but one type of psychological determinism: one is determined by mental, psychological causes. Another type of psychological determinism comes from psychoanalysis: that one’s thoughts and actions can be determined by one’s subconscious. The late philosopher of mind Jaegwon Kim argued that mental causation is a condition for the very possibility of Psychology as a science. Behind both Schopenhauer and Psychoanalysis lies the monism of Spinoza which posits that one is not free but, also, that mentality is as powerful as physicality. More on this at the end.

Psychological Freedom

In contrast, psychological freedom, or “free will”—albeit a vague term—generally means that one’s thoughts and actions are not completely determined by previous thoughts, bodily (neurophysiological) actions, upbringing, culture, nor evolution. It means that the mind at least partly originates thought and action, rather than that thought and action is always an effect of a prior cause. Such freedom from determination allows the possibility of moral praise and blame—one has no complete excuse for one’s actions. Such freedom also entails that certain actions and thoughts are unpredictable.

Proposed Examples of Mental Causation

Will/Desire:

Will to survive to defensive actions?

Hunger to finding food?

Thirst to provisioning drink?

Lust to finding a mate?

Ambition to attaining a qualification?

Compassion to helping others?

Imagination:

Picturing potential moves in chess?

Composing music?

Designing architecture?

Planning the day?

Reason/Intellect:

Logic for technology?

Mathematics for physics?

Conscious Concentration:

Endeavouring to learn an activity (walking, driving, playing an instrument)?

Meditating to consolidate one’s mind?

Focussing on sentences in Hegel to comprehend them?

Epiphenomenalism

Are all of these proposed examples of mental causation merely delusional intuitions, forms of consciousness that are completely impotent, useless? None of the above examples properly fit into the scientific theories we have, in physics but also elsewhere: Jaegwon Kim claimed in 2005 that, “much of cognitive science seems still in the grip of what may be called methodological epiphenomenalism.” Epiphenomenalism is the view that the brain causes the mind to emerge, but that the mind has no causal efficacy back down on the brain and body—i.e. that there is an upward causation but not a downward (or a lateral) causation when it comes to mentality.

Epiphenomenalism, in other words, denies mental causation. The doctrine was famously formulated by Aldous Huxley’s grandfather, Thomas Huxley. In 1874 Huxley wrote—in a paper rhetorically asking whether “animals are automata”—that, “consciousness [is a] collateral product of [the body’s] working, and [is] as completely without any power of modifying that working as the steam-whistle which accompanies the work of a locomotive engine is without influence upon its machinery.” There was simply no evidence for mental causation, he claimed— thus epiphenomenalism: The mind as useless vapour; humans as automata: automatic beings.

But epiphenomenalism is problematic for various reasons—philosopher Friedrich Paulsen wrote in the late nineteenth century that, “If thought can be the effect of [physiological] movements, there is no reason whatever why a movement should not be the effect of a thought.” Upward causation—emergence of mind from matter—is as scientifically problematic as mental causation. There appears to be as little empirical evidence to show that the brain causes the mind as that the mind can have a causal role on the brain: neural correlates of consciousness do not directly show causation either way. But let us look at another problem for epiphenomenalism that argues for the reality of mental causation: the theory of evolution.

EVOLUTION VS EPIPHENOMENALISM

Charles Darwin, a friend yet critic of Thomas Huxley, near the end of his life ended a letter to him with an affectionate bite, “my dear old friend. I wish to God there were more automata in the world like you.” For Darwin, and others such as William James, F. H. Bradley, and Karl Popper, the theory of evolution implied the reality of mental causation, and thus the falsity of epiphenomenalism. As the British Idealist Bradley wrote in 1895:

“when the Darwinian view is applied to the soul [the mind], the soul apparently must be of service. Pleasure and pain, volition and thought must after all be there for something, and must after all do something. For otherwise by this time they would surely be no longer there at all, since, if so, they would be varieties useless yet persisting.”

Likewise the Austrian philosopher Karl Popper—very influential in the philosophy of science, especially with regard to his idea of falsification as the criterion by which something is considered “scientific”—made the same case:

“the theory of natural selection constitutes a strong argument against Huxley's theory of the one-sided action of body on mind and for the mutual interaction of mind and body. Not only does the body act on the mind—for example, in perception, or in sickness— but our thoughts, our expectations, and our feelings may lead to useful actions in the physical world. If Huxley had been right, mind would be useless. But then, it could not have evolved, no doubt over long periods of time, by natural selection.” (1978)

If the mind had no causal power it would not have evolved and maintained itself through presumably long periods of time and through multitudinous species. This is in line with an ancient tenet in philosophy from Plato, the Eleactic Principle: to exist is to have causal powers. Epiphenomenalism, whilst ostensibly accepting the reality of the mental nonetheless transgresses this principle. Has not our conscious intelligence evolved and provided us with the power—the causal efficacy—to build cities, medicine, weapons, technology?

Does not pain cause us to suffer and help us to move? Are not episodic memories a part of the cause of us speaking about “the time when…”? Does not our conscious perception of the world help us navigate it? Does not the feeling of sorrow cause us to help our fellow man, animal, and environment? Does not the love of a parent for their child have any effect upon their upbringing and interaction? Does mind really have no properties that aid survival and development? It seems somewhat absurd to deny this, yet the allure of physical determinism and its scientific accomplishments over recent centuries will not easily give up its claim to explanatory hegemony.

There is thus a counter argument claiming that mind is a ‘spandrel’. A spandrel in biology is a phenotypic trait that evolved as a by-product of something that has an adaptive purpose but has none itself. The typical example is the human chin. Thus, it is argued by analogy, mind may have evolved in likewise fashion having no power, no purpose, thereby harmonizing evolution with epiphenomenalism.

Two immediate problems raise their head: firstly, mind is not an empirically verifiable phenotypic trait as non-empirical privacy seems to be an essential property of mind. Secondly, mind, unlike a spandrel, is not restricted to one species but is seemingly spread throughout the animal kingdom and perhaps beyond. That the same spandrel, mind, emerged in so many species seems highly improbable, as if every species and genera—birds, fish, insects, etc.—had chins. Likewise, the claim is made that mind is akin to a vestigial organ. But the mind is not an empirically verifiable physical organ like the appendix, and, more importantly, vestigial organs once had their own function, their own causal powers—whereas epiphenomenalists would deny even that to the mind: it never played a role.

A further, more theoretical counter claim against mental causation is that the mind can exert control because the mind simply is reducible to certain physical activity in the brain. But this really does not work because the theory reduces mind to matter thereby making matter do all the causal work, rendering mind causally impotent once more—and therefore it faces the evolutionary argument once again: why does mind exist if it does nothing? The problem will not so easily go away.

So it seems that the theory of evolution, via mentality, points to an inadequacy in physics. Physical determinism, but not physics, appears to be wrong; physics appears merely insufficient. But as Karl Popper argued, “Science does not solve all the riddles of the Universe, nor does it promise ever to solve them.” Beyond science, let us look to metaphysics for a glimpse of a possible resolution.

MONIST RESOLUTION?

The aforementioned view that mind is reducible to matter is material monism, materialism, or physicalism. If this cannot accommodate mental causation—determined or free—one may ask what other metaphysical scheme can. Descartes’ dualism struggled with mental causation—the infamous “interaction problem,” and Kant’s idealism considered freedom, along with immortality and God, the most vexing of all philosophical questions. Personally, I consider another type of monism—neutral monism—to hold the key to resolving the conflicting views on mental causation held by the theories of evolution and physics.

Neutral monism, as I use it, means that mind is matter, though neither is more fundamental than the other—unlike in material monism where mind is reduced to the more fundamental matter. Mind and matter appear to be separate, but this is merely a limitation of human cognition, just as someone might think Batman and Bruce Wayne are separate persons even though they are, in fact, one and the same. With regard to mental causation, neutral monism would hold that all physical causation is mental causation, as matter and mind are merely aspects of the same fundamental, neutral, stuff.

This implies that there is no purely physical-to-mental (upward), mental-to-physical (downward), or mental-to-mental causation, but only physical/mental-to-physical/mental causation. Here there is just one causal line, thereby dissolving all the problems associated with presumed “upward” and “downward” causation, whilst making sense of neural correlates of consciousness. If this is the case then the mind does exert control, thus accommodating the evolutionary theory for mental causation, yet it also accommodates physics as physical forces, energy, and their laws exert control—with the caveat that our understanding of “the physical” is incomplete as it omits the mental. Thus neutral monism accommodates mental causation, evolution, and physics.

This panpsychological, monist resolution is essentially the view of Spinoza. But his view was still deterministic, just not merely physically or psychological deterministic. Beyond Spinoza, we may speculate that events, being partly mental, could occur freely, without determination. We have travelled from physical, to mental, to physical/mental causation—but freedom requires a further argument beyond that, which you are free, or determined, to determine.

How does neutral monism deal with the apparent fact that properties of brain and properties of mind are not identical? Viz indiscernibility of identicals. In other words what exactly is meant by the slash in physical/mental?

Lost me in the weeds. I think, therefore I am. I go by lived-experience and once we have seen how our minds cause things--whether directly by instructing and informing our actions OR indirectly by affecting something at a distance (entanglement theory)—that's all we need.