Metaphysics For Psychedelic Therapy

On the Need for Metaphysics in Psychedelic Therapy and Research.

Growing up in a country, Britain, where Philosophy is never taught in schools, I was struck with awe when, reaching university, I first read the metaphysics of Spinoza, Leibniz, Kant, Hegel, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, and the rest. I was suddenly propelled into new ways of thinking about reality, and the essence of my self within those realities. The second time I sustained such an “ontological shock” was when I indulged in a heavy dose of Psilocybin semilanceata mushrooms, liberty caps – primarily motivated by philosopher-psychologist William James' writings on the possibility of achieving mystical states of consciousness via psychoactive chemicals.

This first psychedelic experience altered the trajectory of my life: I searched for philosophical analyses of psychedelic states and found relatively little, so I set off to write about them myself, against the advice of certain academics who thought that this subject for a philosopher was a career-killer.

But I now teach this subject at the University of Exeter. During term time, we host a psychedelic research colloquium twice a month which invites guest lecturers to give a talk and discussion – from shamans to neuroscientists. We have also had a number of psychiatrists and therapists to give presentations, and so we have become familiarized with the present, global state of psychedelic-assisted therapy.

A common issue I have had, as a metaphysician and philosopher of mind, with a number of speakers is the way in which they flippantly conflated – in discussing psychedelic experience – metaphysics with mysticism with spirituality with religion with supernaturalism. Metaphysics has quite a strict meaning in Philosophy which differs significantly from the other terms. I was also struck by the ambiguity and variety of meanings given by the term “integration,” and its many varieties. Integration is the third phase of the (re)growing psychedelic-assisted therapy protocol (which follows the preparatory phase, and the drug session).

Looking at the past and contemporary literature on what was meant by “metaphysics” and “integration” I realized that psychedelic science is poorly informed about the former, and poorly established on the latter. I then realized that a proper understanding of Metaphysics could not only improve the scholarship of psychedelic science, but could also further enhance psychedelic therapy and research, and moreover, beyond the clinic, it has the potential to enrich culture. This was the motivation for my essay, ‘On the Need for Metaphysics in Psychedelic Therapy and Research’ which was published open-access in Frontiers in Psychology in late March 2023. I shall here summarize that text, with additional observations stemming therefrom.

The original article is split into the following sections: Introduction, What is Metaphysics?, What is Mystical Experience?, Psychedelic-induced Metaphysical Experiences, Psychedelic-assisted Psychotherapy, Conclusion: Proposal and Conjecture. The article also contains three diagrams: The Metaphysics Matrix, The PEMM Tristinction, and the Metaphysics & Mysticism Interface. But all of this is premised upon a simple point that is almost a tautology: Metaphysics should be used to integrate and understand psychedelic-induced metaphysical experiences.

That this still does not occur is the deficiency which the article seeks to remedy. In my research for the article I discovered that Albert Hofmann had already made this suggestion: “[A] type of ‘metamedicine,’ ‘metapsychology,’. . . is beginning to call upon the metaphysical element in people … . [Let us] make this element a basic healing principle in therapeutic practice.” (1979)

The word "Metaphysics" comes from the title of Aristotle's text. He did not name it thus, it was rather named (and put together) by a later editor who placed it after (meta) Aristotle's text, Physics. Aristotle himself called the science of metaphysics “First Philosophy,” the science of studying, ultimately Being qua Being – i.e. the primary, fundamental structures of reality. The subdivisions of this first philosophy are still the basis of the academic study of Metaphysics today and includes such subjects as Substance, Cause, Identity, Possibility, Necessity, Space, Time, Eternity, Forms, Relations, Qualities, Deity, etc.

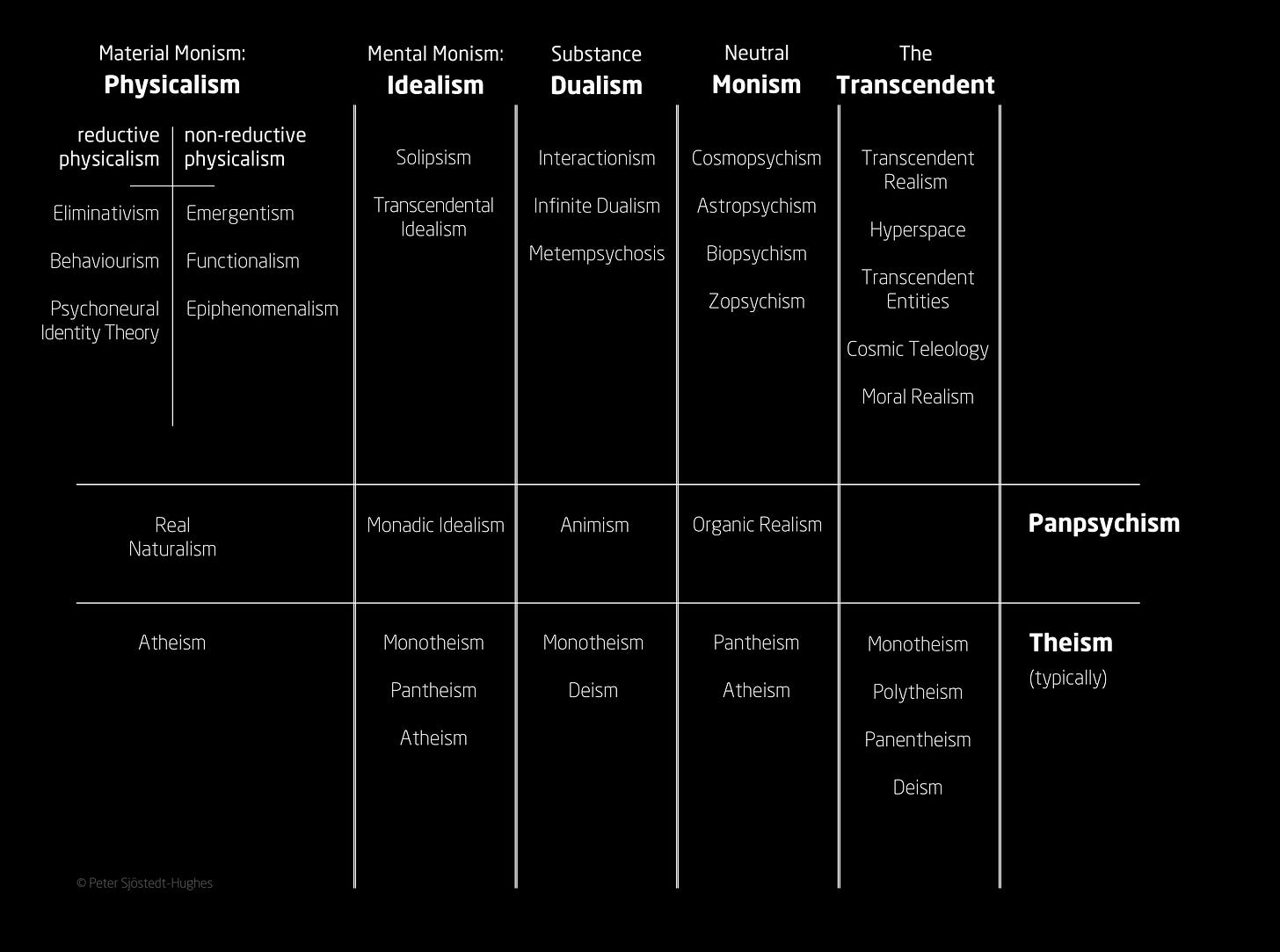

Metaphysics is generally considered to be one of the three core pillars of Philosophy – the others being Axiology (Ethics and Aesthetics), and Epistemology (the study of knowledge). The study of “Substance” (that which sub-stands everything) now concerns the Metaphysics of Mind (and Matter): Is mind reducible to matter (Physicalism), is matter reducible to mind (Idealism), are mind and matter two separate substances (Dualism), Are mind and matter aspects of a more ultimate (neutral) substance (Neutral Monism), Is there another form of existence beyond mind and matter (The Transcendent)?

Fig 1

These five options comprise the column of the Metaphysics Matrix (Figure 1). This Matrix is a development of the one created in my PhD thesis (on "Pansentient Monism"). Panpsychism – that minds are ubiquitous in Nature from mankind, molecule, and beyond – is a row cutting across the columns as there exist physicalist types of panpsychism (e.g. Strawson’s Real Naturalism), dualist types (e.g. Animism), etc. The second row concerns theism which, in its traversal of the columns, includes Pantheism, Deism, Monotheism, Atheism, etc.

This Metaphysics Matrix is not exhaustive, but it aims to serve a practical function in presenting a variety of main metaphysical options – options the experience of which can be induced via psychedelics (e.g. Pantheism: the Universe is God; Animism in Amerindian cultures). I should add that, like an accent, there is no metaphysical default option, and no opt-out: one cannot avoid Metaphysics. As mathematician-philosopher Alfred North Whitehead says: “If you don’t go into metaphysics, you assume an uncritical metaphysics”. There is no escape.

A problem philosophers encounter with both everyday people and many scientists is the unwitting belief that the metaphysical options are only either Physicalism or Dualism. Of course, this is a false dichotomy, and the Metaphysics Matrix, and its accompanying Metaphysics Matrix Questionnaire (MMQ), seek to show that there are more possibilities to understand reality. It provides, as it were, a “Metaphysics Menu” of more than two dishes.

As we can already understand, Metaphysics is not mysticism. Mysticism traces its name back to the Greek root myo, meaning to close (the eyes), or to conceal. From this, we get the word “mystic”, which originally referred to an initiate of the Mystery sects in Ancient Greece, the most established of which were the Eleusinian Mysteries. Plato and Aristotle undoubtedly participated in these Mysteries, which, Bergson argues, may have influenced their metaphysics. The Neoplatonist pagan philosopher Plotinus also spoke of the Mysteries and framed them within his influential monistic philosophy of “The One”, writing that:

“The man who obtains the vision becomes, as it were, another being. He ceases to be himself, retains nothing of himself. Absorbed in the beyond he is one with it, like a centre coincident with another centre. While the centres coincide, they are one. They become two only when they separate. It is in this sense that we can speak of The One as something separate. … The vision, in any case, did not imply duality; the man who saw was identical with what he saw. Hence he did not ‘see' it but rather was ‘oned' with it.” (Ennead VI, 9 [9], §§10–11)

We see here that our concept of mysticism predates Christianity and was from its roots interwoven with a philosophic Metaphysics that sought to understand what the mystical experience meant, thereby adding significance to the experience. In the twentieth century, spurred by William James’ analysis of mystical experience (1902), and because of the decline of the status of Metaphysics (due to the rise of logical positivism, behaviorism, dialectical materialism, etc.), the study of mysticism in the academe became primarily psychological rather than ontological, and quantitative rather than qualitative.

James offered four marks of the mystical experience: noeticism, ineffability, passivity, and transience. Though James himself was very much infatuated with metaphysics (especially that of Bergson, Fechner, and Hegel – he even claimed that nitrous oxide allowed him to better understand Hegel), this metaphysical part of his thought was left behind in Psychology’s uptake of examining mystical states. Instead, methods were sought to measure mystical experiences in psychedelic trials based on James’ then Walter Stace’s (1960) criteria (The One; The immanence of The One in all things; Sense of objectivity or reality; Blessedness, peace; Feeling of the holy, sacred, or divine; Paradoxicality; Ineffability; Non-spatiotemporality). Questionnaires were based on these criteria, which questionnaires are still used today that provide data for cold analysis.

Fig 3

There are a number of issues with this procedure. Firstly, much psychedelic experience is not mystical experience. Psychedelic experience is wide and may include simply laughing, or bodily feelings, enhancing creativity, improving hunting skills, etc. One must distinguish psychedelic experience from mystical experience from metaphysical experience, despite overlaps (see Figure 3: the PEMM Tristinction). Secondly, as I list in my original article, there are a variety of definitions of mystical experience many of which are omitted today (e.g. going beyond good and evil).

Thirdly, some scholars argue that there is no universal, common core experience of mysticism (e.g. unity), but rather they believe that one’s culture determines such experience itself, as well as the interpretation. These “Contextualists” believe that culture conditions experience; “Perennialists”, on the other side, believe that such experiences decondition one from culture. I think a middle way is probably correct. A fourth issue is whether, even assuming perennialism, drugs can induce a genuine mystical experience. R. C. Zaehner argued that they could not, contra Aldous Huxley and James.

A fifth issue is whether such mystical experiences should be considered as veridical (objectively true) or as delusional. If the latter, then, sixthly, an ethical problem arises: the “Comforting Delusion Objection” to psychedelic therapy: “Is it not unethical to treat people by instilling delusions upon them?” My problem with this objection is that it assumes that a metaphysical reality (usually Physicalism) is true as a basis for criticizing other metaphysical positions as false (it also assumes an ethical position). We are not yet able to do this because no one agrees upon what reality is! Without knowing what reality is, we cannot assert what delusion is. The mind-matter problem, or the “hard problem of consciousness”, shows that we do not know what the relation is between mind and matter. The options to answer this problem are the items on the Metaphysics Matrix (Physicalism, Dualism, Idealism, Monism, etc.). The mind-matter problem keeps the metaphysical options open.

Neuroscientists, psychiatrists, therapists, et al., should retain humility in realizing this limitation to our knowledge. Again, there is no neutral, default position to fall into here: all positions, including Physicalism, have arguments in their favor, and arguments against them. A seventh issue with using such mysticism questionnaires in psychedelic trials is that they are inadequate to capture many altered states of consciousness. Metaphysical experience subsumes mystical experience – that is to say that most so-called “mystical experiences” can be included within the notion of “metaphysical experiences”, but the latter includes more experience types. For instance, Sir Humphry Davy proclaimed an Idealist insight after taking 200 pints of nitrous oxide, but Idealism is not an item on mysticism questionnaires.

Fig 2

One can differentiate “metaphysical experience”, or “experiential metaphysics” from “intellectual metaphysics”, the latter is what one studies at university. The former is the experience associated with certain metaphysical systems. William James writes, for instance, that “in the nitrous oxide trance we have a genuine metaphysical revelation” (1902). Deleuze stated that the metaphysical position that is Spinozism (a type of Neutral Monism) could be attained via an “extraordinary conceptual apparatus” or via a “sudden illumination … a flash. Then it is as if one discovers that one is a Spinozist” (1970). (See Figure 2: the Metaphysics and Mysticism Interface.)

Reconceptualizing mystical experience as metaphysical experience has two core benefits: firstly, it expands the net by which one can capture a person’s exceptional experience. Secondly, because metaphysical experience has an associated intellectual rationalization, the experience can now be discussed in more detail, if desired, and moreover, it need not be immediately dismissed as a delusion. Experiences of panpsychism, for example, can be discussed via the apparatus of Spinozism, for instance. It is such discussion that I propose become an additional and optional part of the integration phase of psychedelic-assisted therapy.

I conjecture that the peak unitive Monist experiences that recent evidence suggests have the most therapeutic power can be amplified by discussing them further in Metaphysics Integration. Furthermore, by showing that such experiences have a reputable, serious academic legacy may halt the later dismissal of them as delusions, thereby promulgating the long-term positive effects of the experience upon the participant. Further still, presenting these metaphysical options to therapists themselves may mitigate any ideological dogma that they may harbor.

Again: metaphysical experiences should be integrated and understood with recourse to metaphysics. I say “additional and optional” because not all psychedelic experiences are metaphysical, not all people might want to discuss these deep matters, and it should not replace therapeutic practice generally of course – it should merely be an additional tool that therapists can utilize. Psychedelic-assisted therapy differs from other kinds with the inclusion of metaphysical experiences; but therapists, especially in English-speaking countries, have mostly not been trained in Metaphysics. So this is where Philosophy can emerge from its theoretical ivory tower and apply itself in practice.

The actual practicalities of this will involve a course for therapists, and an associated metaphysics manual – a project that I am currently setting in motion. It is not easy to convey complex metaphysical positions to people who have never studied them before, but I believe useful basics can be expressed – the MMQ strives to begin with such expression, but there is much more work to do. But, we see here the potential harmony that can transpire when the “psychedelic turn” and the “metaphysical return” of the twenty-first century, converge.

Editor’s note: Feed Your Head does not take a position on the ultimate nature or efficacy of psychotropic substances. As such, consultation with health professionals and/or spiritual leaders is strongly advised.

The only thing metaphysics has to do with psychedelics is in the realization that all experiences are real reverb though all experiences are not of something real.

--

All things are real as a pattern in the mind. Some of them have an external referent. The transcendent is the universe as it is beyond the perception of a mind and drugs can't get you there; only increasing the resolution of your measuring instruments or your logic.

Kind-of lost me there. Whatever these states of mind are, I would imagine that most human beings may be capable of achieving them without drugs. I believe in our consciousness and its infinite capacities.