Melancholy + Hope: The Sound Of Meaning

The common language of Chopin and Radiohead

For a few decades now, I’ve endeavored to listen to as much great music as I can. Somehow, it just seems wrong to leave this plane without having sampled the very best of what it has to offer. So whenever I have a long drive, I load up a symphony or a shorter series of related pieces, like Chopin’s Preludes. I did this today, heading north on I-95, when I realized two things at once: that Chopin’s Prelude in E Minor is strikingly similar to Radiohead’s “Exit Music (For a Film),” and that the most transcendent musical experiences are those that contain a hefty dose of melancholy alongside hope.

What I discovered felt both obvious and strangely revelatory: a direct emotional and musical kinship between these two pieces. I’m not trying to be clever here, nor academic. You can hear it simply by listening, and then listening again, and realizing that the two pieces seem to speak the same inner language across nearly two centuries. They feel like different dialects of the same profound but painful idea.

A Common Language

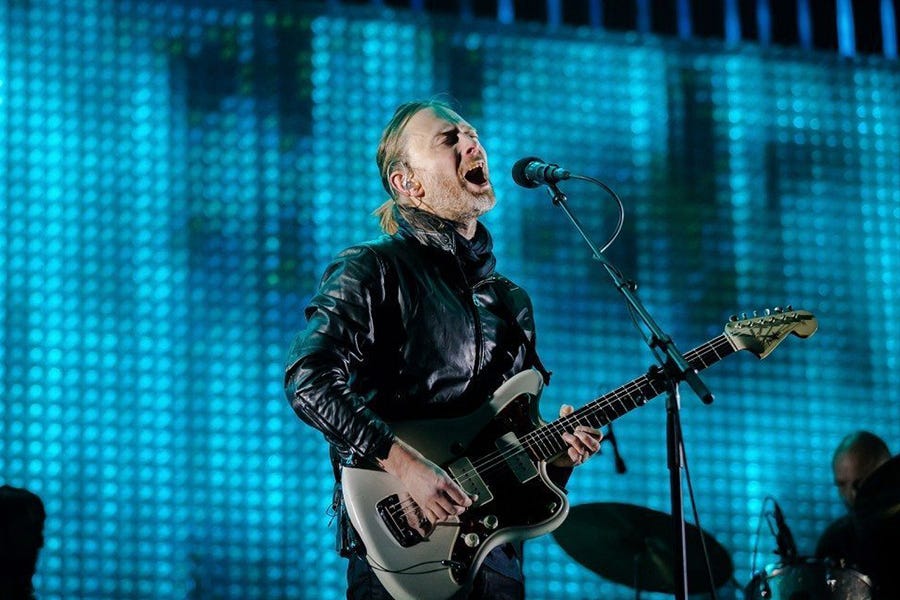

Image: happymag.tv

Chopin’s E minor Prelude is among the starkest expressions of restrained grief in Western music. It unfolds as a slow harmonic descent, almost resigned, yet exquisitely attentive. Nothing in the piece shouts. The sorrow is quiet, dignified, and unavoidable. What gives it its power is not melody in the conventional sense, but the way harmony itself seems to sigh, step by step, toward something darker without ever becoming meaningless.

“Exit Music (For a Film)” operates in a strikingly similar way. The song is spare, nearly skeletal at first, with a vocal line that feels more spoken than sung. Like the Chopin prelude, its emotional weight lives in the harmonic movement beneath the surface. The chords descend, tension accumulates, and release is delayed. Even when Thom Yorke’s vocals grow louder, more forceful, and almost unbearably sad, it never feels like an arrival or a resolution. The sadness remains central, but it’s an active sadness, charged with intention, and through it all, it somehow remains strikingly beautiful.

What links these two works is not quotation or influence in any obvious sense, but a shared emotional geometry. Both pieces inhabit that rare space where melancholy and hope coexist. They do not negate sorrow, but they refuse to let it collapse into despair. There is motion in both, a sense of continuation. Something is still being carried forward, even as something else is being lost.

This balance is what gives the music its transcendent quality. Pure sadness eventually closes in on itself. Pure optimism can feel unearned. But when music holds both at once, it mirrors lived experience more truthfully. We grieve because we value. We ache because something mattered. In both Chopin and Radiohead, the pain feels meaningful rather than empty.

The Sound of Meaning

Image: thecollector.com

In this sense, elite music captures something profound about existence itself. What can be more confusing than the dizzying array of beauty, meaning, and goodness in this world that so often lives alongside the most intense and unacceptable ugliness, evil, and seeming meaninglessness?

As writer Anne Lamott once quipped:

All truth is a paradox. Life is a precious, unfathomably beautiful gift, and it is impossible here, on the incarnational side of things. It has been a very bad match for those of us who were born extremely sensitive. It is so hard and weird that we wonder if we are being punked. And it is filled with heartbreaking sweetness and beauty, floods and babies and acne and Mozart, all swirled together.

Perhaps this is why music like this feels spiritual even when it is not overtly religious. It reaches a place that exists before explanation. It does not tell us what to think or what to believe. It simply allows us to sit inside complexity without forcing closure. That experience can feel revelatory because it is rare and because it is deeply human.

The greatest music often lives in this narrow emotional band. Chopin, writing alone at the piano, and Radiohead, working within a modern, amplified idiom, arrive at the same truth from opposite ends of history. They show that sorrow and meaning are not opposites, and that hope does not require denial. Sometimes hope is simply the decision to keep listening.

That may be why these pieces linger. They do not promise that everything will be fine. They offer something quieter and more durable. They suggest that even in moments of darkness, there is still coherence, still beauty, and still a reason to stay present. When words fail, this is the music many of us return to, because it articulates something we recognize, even if we cannot fully explain it.