Mama, I’m Coming Home

Adieu to Ozzy, Prince of Darkness

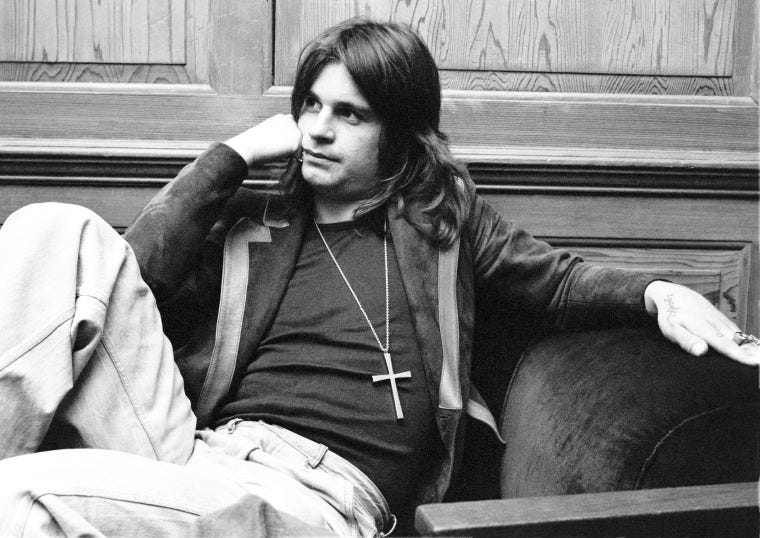

Image: ajournalofmusicalthings.com

We have entered, as it seems,

Realm of magic, realm of dreams.

—Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, “Walpurgis Night,” from Faust, Part Two

The world lost a prince this week. Not one of its geopolitical war pigs, born in the lap of luxury and exploiting the precarity of the masses in order to further enrich the global elites. Rather, a true prince, raised among the people and chosen by them as an exalted fellow traveler, simultaneously larger than life and profoundly familiar. I am speaking, naturally, of the “Prince of Darkness,” Ozzy Osbourne, who passed away earlier this week. The days and weeks to come will, no doubt, produce a smorgasbord of editorial memorials and biographical sketches. I offer but a simple farewell to a man who had one of the deepest impacts on the formation of my identity in my younger years.

Shadows of a Panic: The Cultural Scapegoating of Ozzy Osbourne

My childhood was marked by what we now know as the great “Satanic Panic” of the mid- to late-1980s. In the technical sense, the etiology of the Panic is considered to be the 1980 book, Michelle Remembers, coauthored by Canadian psychiatrist Lawrence Pazder and his patient (whom he later married), Michelle Smith. Rooted in the widely discredited study of repressed memories, the book outlines graphic depictions of Satanic ritual abuse that Michelle allegedly suffered as a child at the hands of her mother, whom she accused of membership in a Satanic cult. Though lacking in all evidence and grounded in pseudo-science, the widespread popularity of the book—Pazder’s appearance on the Oprah Winfrey Show and the countless accusations and investigations the book inspired—point to a deeper cultural pathology.

Reactionary anxieties surrounding seismic cultural shifts having to do with religion, race, and gender (among which a generation of women entering the workforce), had triggered a pervasive uneasiness about the upbringing and fate of America’s children that reached far beyond the conservative Christian circles from whence it sprang. None other than Satan himself, it seemed, would come to fill in the gaps left by our absent parents; and the panic was ubiquitous. Role-playing games like Dungeons & Dragons were forbidden by parents, as were books with supernatural themes (excepting those of explicitly Christian provenance). But the domain to which the most painstaking attention was paid was the music that children were consuming.

Rock ‘n’ roll has long been the music of rebellious youth, from the hip gyrations of Elvis Presley to the drug-infused, antiwar music of the 1960s counterculture. But with the birth of heavy metal (thanks, in large part, to Ozzy himself as the frontman of Black Sabbath), that rebellious impetus began to assume a demonic visage, one that dovetailed perfectly into the Satanic Panic of the 1980s. Albums such as AC/DC’s Highway to Hell, Slayer’s Reign in Blood, Mötley Crüe’s Shout at the Devil, and Iron Maiden’s The Number of the Beast played upon the imagery of the occult, at times for sheer anarchic revelry, sometimes for storytelling purposes or for the exploration of the darker facets of human life. Images of demonic figures, pentagrams, inverted crosses, and nightmarish hellscapes emblazoned album covers, t-shirts, and denim jackets.

This led to broader and more risible accusations concerning the Satanic preoccupations of musical acts. AC/DC, it was said, stood for “After Christ, Devil Comes,” or “Against Christ, Devil’s Children” (depending on who you asked). KISS, they said, stood for “Knights In Satan’s Service.” Even bands as innocuous as The Eagles were retrofitted with accusations of Satanic dalliance when rumors surfaced that their 1976 album, Hotel California, celebrated Anton LaVey’s California-based Church of Satan, with some even asserting that LaVey himself appears in the album’s gatefold (he doesn’t).

Then came the murders. In March 1986, 16-year-old Sean Sellers shot and killed his mother and stepfather as they slept in their bed, later claiming to be a dedicated Satanist possessed by a demon. In 1988, 14-year-old Boy Scout Thomas Sullivan Jr., also an avowed Satanist, murdered his mother before taking his own life. But the most prominent of these cases is without question the infamous “Night Stalker,” Richard Ramirez, who terrorized the areas of Los Angeles and San Francisco from April 1984 until his capture in August 1985.

Ramirez would often scrawl occult symbols at the scenes of his crimes, left behind an AC/DC ballcap at one site, claimed an inspiration from AC/DC’s song, “Night Prowler,” and appeared in court with a pentagram drawn on his hand, shouting, “Hail, Satan!” The topic of heavy metal music and its connection to the occult and impact on young listeners became the constant fodder of televangelists, daytime talk shows, and popular magazines.

Allegations of secret occult rituals and suspicions regarding backmasked Satanic messages on albums became topics of Sunday sermons and family gatherings. Horror films like the 80s cult classics The Gate and Trick or Treat, (in which Ozzy makes an appearance), capitalized on these rumors. This obsession would ultimately culminate in the work of the “Washington Wives,” who founded the Parents Music Resource Center (PMRC), which eventually led to the parental advisory warning system still in use today.

But those of us from that era know that, among this assortment of “dangerous” figures, none were so maligned in the public eye as the Prince of Darkness himself. In hindsight, this seems a little odd, given how relatively benign Ozzy’s imagery and lyrics were in comparison to many of his 80s metal contemporaries, or given that The Osbournes would eventually be a wildly successful reality show, popular across various demographics (including my mom’s), or given the fact that “Crazy Train” is now a staple of high school marching band performances.

And where other artists seemed often to employ demonic and occult imagery primarily for the sake of shock or theatrics (think KISS or Mötley Crüe), Ozzy’s infatuation with such imagery always seemed more nuanced and to spring from a deeper, more authentic source. I suspect the elevation of Ozzy to the status of cultural heavy metal antichrist likely stemmed from the twin elements that he was a singular figure, and one of immense popularity and notoriety.

Unlike the famous mascots at the forefront of acts like Iron Maiden (Eddie) and Megadeth (Vic Rattlehead), Ozzy was a flesh-and-blood human being, bearing all the gravity and identifiability of the face. And unlike the vague configurations of countless bands (AC/DC, Maiden, Metallica, Megadeth, Slayer, W.A.S.P., etc.), Ozzy was, on his own, the icon of his sound. While his most devoted fans recognize the distinctions between the eras of guitarists Randy Rhoads, Jake E. Lee, and Zakk Wylde, they have always been understood as the musical muscle in support of the true figurehead, Ozzy.

And finally, while someone like Mercyful Fate’s frontman, King Diamond, may have openly declared himself a LaVeyan Satanist (which is not synonymous with “Satan-worshipper,” mind you), Diamond’s popularity was contained to a relatively small but enthusiastically loyal fanbase, where Ozzy was universally and globally recognizable, in part due to his already-established fame with Black Sabbath, but also owing, no doubt, to the amplified media coverage of some of his outlandish antics. His two-syllable name, the worshipful chant of throngs of adoring fans worldwide, Ozzy was an obvious scapegoat, an anti-messiah, for the Satanic Panic.

The rumors that surrounded Ozzy were nothing short of absurd. He had sold his soul to the devil, they said. (Of course, the Black Sabbath compilation, We Sold Our Soul for Rock ‘n’ Roll, certainly didn’t discourage such speculation). Detailed descriptions circulated concerning elaborate ritual animal sacrifices, allegedly performed at his concerts. Some even suggested that he had bitten the head off a live bat on stage. (OK, OK, “Two Lies and a Truth”).

In the pre-internet days, scarelore and bizarre urban legends concerning celebrities spread unchecked and unabated through everyday life, and the human fascination with the fantastical, coupled with the aforementioned cultural anxieties and lack of any independent source of verification, helped entrench such stories as considered fact across multiple community circles.

Forbidden Fruit: A Personal Awakening Through Music

Image: distractify.com

For many parents, my mom included, Ozzy was the non-negotiable prohibition, the line that could not be crossed. Even as I was allowed to listen to bands like AC/DC, Twisted Sister, Quiet Riot, and Mötley Crüe, my mother would not bend when it came to Ozzy. As prohibitions often do, this made him something of an enticing forbidden fruit to a curious young boy.

I was approximately ten years old when my break finally came. The home of my uncle Jack and aunt Janice was a frequent Saturday night destination on the weekends I spent at my dad’s house growing up. It was one of my favorite places on Earth, mostly because of my cousin, Jesse. One year my senior, Jesse, was my highly cherished contraband connection. He and I shared an enthusiasm for the outdoors, an infatuation with mischief, and a love for hard rock music.

When Saturday evening would set in, Jesse and I would often sit on the floor of his bedroom listening to the forbidden sounds of the devil’s symphonies. I can still feel the electrifying sense of awe tinged with fear that swept through me the first time he pulled out Ozzy’s 1983 album, Bark at the Moon, a fear deriving in part from the cover image. Portraying a convincingly werewolf-costumed Ozzy, perched high in a tree beneath a brightly glowing moon, it was an uncanny and paradoxical combination of the strange and the familiar.

With all of the theatrical aggression, but lacking just a bit of the plasticity characteristic of the “hair metal” on which I had cut my teeth, there was an undeniable edge to the sound of the more seasoned Ozzy. The furiously distorted guitar chugs and abrupt heaviness of the drums in the opening of the album’s title track grabbed me from the beginning. But nothing could prepare me for Ozzy’s voice, the nasally vibrato lending it an almost metallic operatic sound. But through the course of the album, yet another distinctive and alluring characteristic emerged, setting him apart from the herd—Ozzy’s incomparable talent for lyrical storytelling. I was hooked.

I then went to work on the arduous task of convincing my mom that Ozzy was not nearly as bad as she thought, and with time, I wore her down. The year after my first encounter, we had cable television installed in my mother’s house, bringing with it the famed MTV, which, until that time, I assumed was available only to the more privileged. One evening, with MTV providing background noise for other activities in the house, an old video for “Iron Man” came on, and though he looked more like a 70s hippie than the metal god he would become, (a perception augmented by the video’s psychedelic visual effects), I quickly recognized the frontman, and thus discovered the catalog of Black Sabbath.

Over the next few years, through a combination of Christmases, birthdays, and my meager weekly allowance, I would procure every Ozzy album from Blizzard of Ozz to No More Tears, (with one exception, his double-live album, Speak of the Devil—my mom’s final holdout), along with a number of the albums of Sabbath. The Ozzy in my music collection far outnumbered all the other musical influences of my youth.

The Storyteller in the Shadows: Ozzy’s Lyrical Humanity

Image: nbcnews.com

The thematic darkness of Ozzy’s oeuvre was compelling to me, even as a pre-teen. In many cases, this issued as an elevation of social awareness, even protest. Consider, for example, “War Pigs,” one of the greatest antiwar songs ever penned, covered in various guises by numerous artists, including, most recently, T-Pain and Ozzy’s fellow Birminghamians, Judas Priest. The song was initially titled “Walpurgis” after the mythical Walpurgisnacht, the witches’ sabbath sketched in vivid detail in Goethe’s Faust, imagery meant to evoke the seemingly spiritual or mythical allure that war holds in the human mindscape.

Long before the documented societal schizophrenization now associated with social media, “Crazy Train” articulated a media-saturated world dedicated to dividing the masses. “Miracle Man” highlighted the amoral hypocrisy of American televangelism. Or consider The Ultimate Sin, an album whose tracks deal with nuclear fantasy and ecological catastrophe. There is something of a hippie ethos in much of his catalog, but one lacking the pollyannish optimism of much of the music of the ‘60s.

Other times, Ozzy’s darkness expresses a deep and personal confrontation with the more dreadful aspects of human existence, something of an Edgar Allan Poe robed in guitar distortion and heavy percussion. “Suicide Solution” and “Mama, I’m Coming Home” focus frankly on the theme of addiction (a topic of great significance to Ozzy). “Changes” and “Close My Eyes Forever” speak to the excruciating complexities of romantic love. “Goodbye to Romance” captures the morose hollow of loneliness. “Fire in the Sky” addresses the collapse of childhood illusion on the way to adulthood. And in every single song, Ozzy’s humanity shone through.

It is no exaggeration to say that, in a very real sense, Ozzy was one of my best friends as I entered my teenage years. With a father I rarely saw, a stepfather typically absent for a week at a time as a long-distance truck driver, and a mother who worked herself to exhaustion in full-time employment and desperately trying to care for my younger brother and maintain all other roles in the household, I spent much of my youth alone in my isolated upstairs bedroom, trying to stay out of mom’s way. I would pass literal hours sitting in my beanbag chair, the room’s only source of illumination being one of those Radio Shack stoplights, flashing red, yellow, and green in various combinations.

No television on, no other sounds but the ones coming from my stereo. More often than not, Ozzy was my companion, his unmistakable voice something of an emotional balm. Through hours of play, I wore out my cassette copies of Black Sabbath’s Greatest Hits, as well as Ozzy’s No Rest for the Wicked. And as the loneliness of childhood gave way to the angst of teendom, Ozzy was the gateway drug that eventually led me to the heavier sounds of Metallica, Megadeth, and Slayer; but with Ozzy as the ever undeniable godfather who had ushered me to their door.

I suspect that Ozzy’s enduring popularity, now spanning multiple generations of varied classes of fans, is best understood as a function of his authenticity, the humanity that spoke to me even as a child through the heavy guitars and the mythical, demonic narratives. As a youth, I remember crossing the street each month to the local, family-owned grocer to pick up the latest issue of Hit Parader, a music magazine established in the 1940s that eventually found its niche with an exclusive focus on heavy metal music in the 1980s.

Of all the issues I purchased, all the articles and interviews I read, all the full-page color prints I cut out and pasted on my wall, one photograph alone remains in my memory. It was in the small editorial section that would show one of the revered heavy metal artists reading a copy of Hit Parader, typically in a hotel room or on a bus. This particular photograph, however, was of Ozzy, in a bathroom stall, pants around his ankles, seated atop the porcelain throne. An enormous smile stretched across his face, he proudly held up his copy of Hit Parader. The image has stuck with me for almost forty years for the endearing nature of its utter banality.

More Than a Myth: Remembering the Man Behind the Legend

The fact that, despite his larger-than-life rock god status, Ozzy most fundamentally celebrated his humanity, sometimes joyful, sometimes mundane, sometimes horrifying, but always real. It was his humanity that shone through in his stage performances when he would ceaselessly express his undying love for his fans. It was his humanity that eventually won over the folks who had so scorned him in the 80s, when they later saw him on The Osbournes, exasperated over his children’s irritable attitudes, scolding his defiant cat, fumbling with the remote control, or comically chiding Sharon for the presence of bubbles on stage.

It was the humanity of a soul that traveled through the depths of Hell, but emerged with a gratitude and a joy that radiated from his perseverant smile, even as he would relapse into the abyss countless times through the course of his life. A humanity forged in the extremes of human experience, recognizable, albeit in varying modes and degrees, by us all.

That humanity accompanied me through some of the most confusing periods of my young life. And I will be forever grateful.

“Goodbye to romance, yeah. Goodbye to friends, I tell you. Goodbye to all the past. I guess that we’ll meet, we’ll meet in the end.”

Adieu to the Prince of Darkness.

I don’t think I’ve ever listened to a single Ozzy Osbourne song, Vern. (yeah, I know: poor boomer.) But I really liked this article! Thanks!

When I saw The Osbournes on the telly, it seemed to me that all that Satanic imagery was a send-up. The 60s didn't just have a pollyanna sensibility. There were protest songs that detailed the atrocities of the warmongers and bigots. Our "darkness" avatar was Bob Dylan. Anybody hearing about Hollis Brown or William Zantzinger learned about racism and hatred. Ditto Masters of War, Blowin' in the Wind, A Hard Rain's a-Gonna Fall, etc., did not see life through rose-colored glasses. We didn't even need Satan to see the evils of plain old humanity. And, once Dylan moved beyond straight-out protest, his songs took on more mysticism and esoterica. I guess every generation needs different symbols to express its pain. Turn, Turn, Turn. . . .