Making Sense of Mysticism

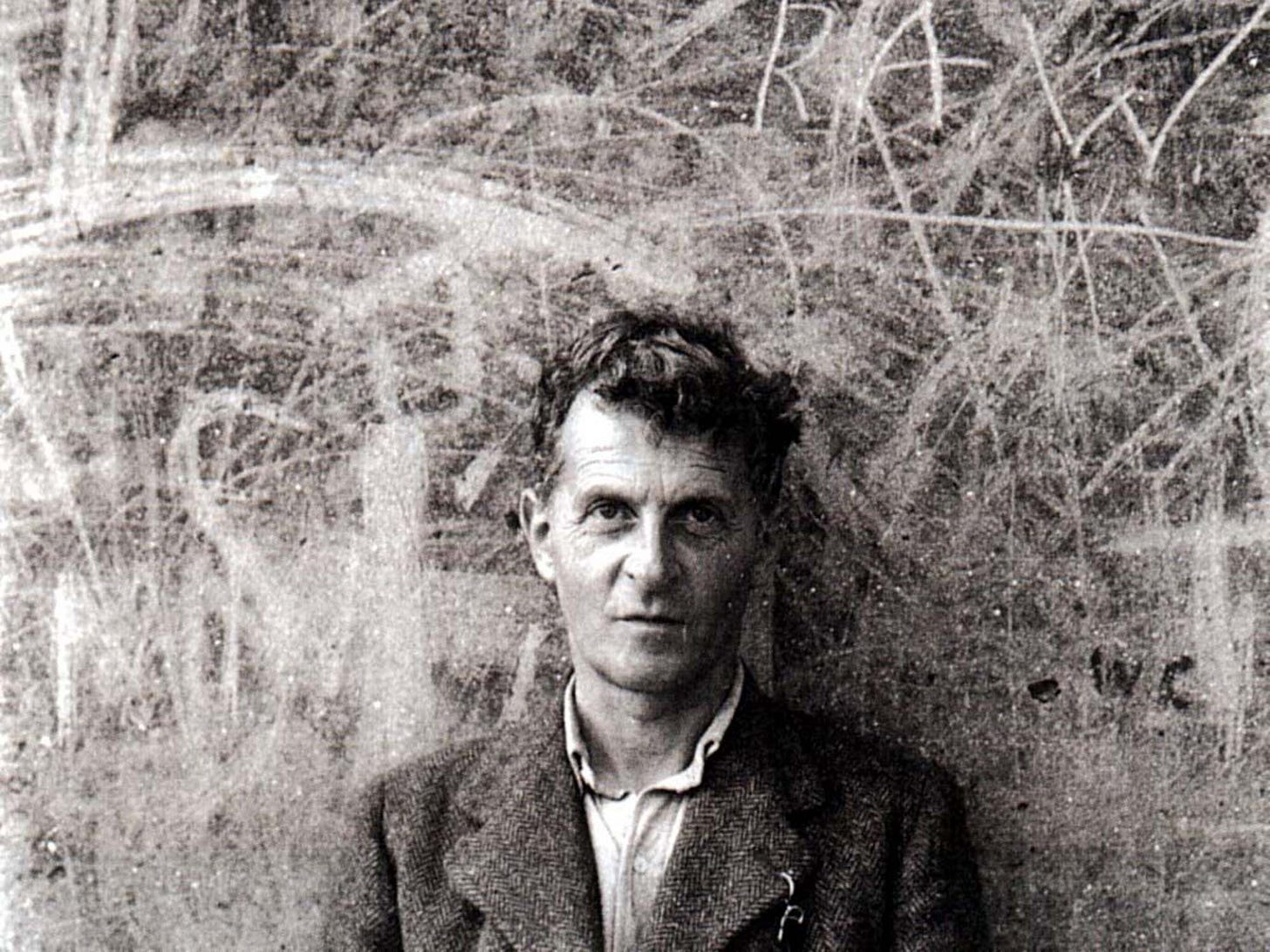

When Wittgenstein Said the Unsayable.

Image: medium.com

Can we make sense of the mystical?

For some people, the word ‘mystical’ carries purely negative connotations. To be accused of mysticism by a hard-headed materialist is to be charged with obscurity, eccentricity, and irrationality.

Perhaps, like me, you’re not inclined to go that far. Even so, “the mystical’ certainly carries strong associations of crystals and patchouli oil. As a character trait, it’s usually at odds with the contemporary ideals of rationality and pragmatism—not to mention the ability to turn up to appointments on time.

Perhaps for these reasons, many philosophers steer clear of all things mystical. But a handful have tried to use reason to explain— and occasionally even justify—certain mystical experiences. And perhaps the greatest philosophical sympathizer of mysticism was the Austrian-Jewish thinker Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951).

Wittgenstein’s mysticism is remarkable partly because he leads us there via an austere philosophy of language and logical analysis. Not only does this create a striking contrast between his arguments and their conclusions, but it also makes Wittgenstein well-placed to persuade a skeptical mind of the credibility of mystical experiences.

So what did he argue?

Pictures of the world

Wittgenstein famously only published two books in his entire life. One was a dictionary for elementary school children, and the other was arguably the greatest philosophical work of the twentieth century. Its name is the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921).

In the Tractatus, Wittgenstein seems, at least to begin with, to be interested in the capacity of language to represent the world.

The very first line of the book tells us that “[t]he world is all that is the case.” In the way Wittgenstein uses it, “the world” isn’t a geographical concept, referring to planet Earth and all the animal, vegetable, and mineral things on it. Instead, “the world,” for Wittgenstein, is the sum total of facts, of states of affairs.

This is a very abstract idea, but it can be made a little clearer by connecting it to Wittgenstein’s theory of language. According to Wittgenstein, what language does when it’s working correctly is “picture” a fact.

For example, if I say, “I own a dog called Rosie,” then that statement successfully pictures a fact. It is indeed the case that there is a dog called Rosie, whom I own—and so the combination of words in my statement maps onto that fact, which is just one of the infinite number of facts making up the world.

Imagine, by contrast, that I’m listening to a piece of music and say, “This song smells too loud.” This sentence might be grammatically correct, but as a statement, it fails to map onto any fact by virtue of its total illogicality. Not only do songs not have a scent, but even if they did, they wouldn’t smell loudly. So my statement says nothing about the world and is, quite literally, non-sense.

Here we have perhaps the key distinction made in the Tractatus: between language that successfully pictures facts collectively constituting the world and language that fails to do so.

But what does this have to do with mysticism?

Nonsense

Image: philippbanken.blogspot.com

Some of Wittgenstein’s early readers completely misunderstood what he was trying to argue about life, reality, and meaning.

The Vienna Circle of logical positivists, for instance, saw in Wittgenstein a like-minded ally. They believed in the absolute superiority of ideas that were either analytically true (like the truths of mathematics) or else capable of being empirically verified (like scientific hypotheses).

As such, they sought to banish all non-scientific and “irrational” language from intellectual and public discourse. This meant that God, metaphysics, and intuitionism were to be cast out of public life in favor of science, logic, and mathematics.

The Vienna Circle’s extreme enterprise was, they claimed, partly justified by Wittgenstein’s distinction between language that successfully pictures facts making up the world and language that fails to do so and therefore counts as nonsense. To the Vienna Circle, religious, metaphysical, and mystical language were all examples of the latter—mere nonsense.

But this was actually a complete misunderstanding of what Wittgenstein was arguing. Because, in fact, he wanted to identify and hold open the space of meaning occupied by the mystical.

Showing the unsayable

Image: oleniski.blogspot.com

The big reveal comes two-thirds of the way into the book. After sixty pages of truth tables and formal logic, the metaphorical acid kicks in, and Wittgenstein pronounces a pair of gnostic dictums like an acolyte of some ancient hermetic order.

“The world and life are one,” he says. “I am my world. (The microcosm)”.

Esoteric statements like these weren’t entirely lost on Bertrand Russell, Wittgenstein’s on-off colleague. After reading a draft of the Tractatus, Russell told a mutual friend that “I had felt in his book a flavor of mysticism.” Even so, Russell was astonished to find out that Wittgenstein had “become a complete mystic. He reads people like Kierkegaard and Angelus Silesius, and he seriously contemplates becoming a monk.”

Unbeknownst to Russell, Wittgenstein’s interest in monastic life was down to several mystical experiences he’d had. And the most valued of these—Wittgenstein’s “experience par excellence”—was being overwhelmed in wonder at the fact that the world exists.

Perhaps you’ve felt this way too, even just once. When staring at the wide open sky or watching your children play. Feeling consumed by the fact that some particular thing, that anything, is at all. This, Wittgenstein claims, “is the experience of seeing the world as a miracle.”

Wittgenstein says that people who’ve had an experience like this will typically find in it an absolute value. They’ll become aware of a goodness that isn’t relative or subjective but “supernatural.” A good that transcends the world itself and breaks in upon it.

The problem, however, is that words— including those I’ve just used—only ever picture facts that make up the world. So this means that I’ve just done something impossible: used language that applies only to the world to try to describe something beyond it.

For this reason, Wittgenstein makes a crucial distinction between “saying” and “showing.” What we say with language are pictures of the facts that make up the world. But language (as “pictures”) also lets us show what lies outside the world, acting like a signpost.

When language does the latter, it may not be working “properly,” – but it’s doing something arguably more important still: reaching beyond facts and toward something that accounts for said facts. God, perhaps, or the Good, the Beautiful, or the Sublime.

Whenever we use language to describe any of these, we are talking non-sense. But it’s never mere nonsense. And for Wittgenstein, that makes all the difference.

Back to reality

Of course, Wittgenstein’s defense of mystical experiences is only persuasive if we’ve had such experiences. Otherwise, there’s nothing for us to try to show. For people like myself, who’ve never encountered God, for example, it’s easy to be skeptical about other people’s claims to have experienced the divine.

But then other people might say the same about the mystical experiences I have had – such as wondrousness at the existence of the world or feeling a sense of oneness with it. And I would not want anyone to doubt their validity.

So perhaps we should keep an open mind. We can read and listen to accounts of mystical experiences that we’ve not had in the hope that for us, too, the mystical will make itself manifest.

And Wittgenstein can show us the way.

Language is what humans use to cooperate regarding the things and experiences we share in common. "This Juice tastes good." When words become clumsy is when we have an experience unique to us. A new taste is compared to a combination of old tastes yet we say, different, it's own flavor. We communicate that it is difficult to describe. Emotions are experiences similar but different for each person. This is the realm of poetry. We need a creative use of language to explain an intense or subtle emotion to another person not feeling it. Mysticism is a unique emotional spiritual experience which language by it's nature fails to capture. We can make the attempt but we must be very careful how we describe it and caution the listener to be careful not to interpret it literally, for we are out of charted territory and there be monsters here.

What a delightful synchronicity to read this essay within twenty-four hours of reading about particle physicist Heinrich Päs' new book "The One: How an Ancient Idea Holds the Future of Physics". I hope that before too long, Rabbi Jacobs will interview the author for the Beyond Belief series. Somewhere, Spinoza and others are smiling!