Is There a Purpose to Life?

Are living things the products of design, chance, or something else?

Have you ever come across an idea that fundamentally changed the way you thought? Or perhaps one that gave a name to an intuition you’d always had and were sure was correct but couldn’t articulate?

An idea that transforms or crystalizes the way you think about the world is sometimes known as a threshold concept. They’re so named because they serve to change your thinking, are hard to undo, and consequently have a longstanding impact on the way you see yourself and the world.

As you read the above, a threshold concept from your own life might have come to mind. Everybody will have different ones, rooted in personal experience and perhaps linked to your formative years.

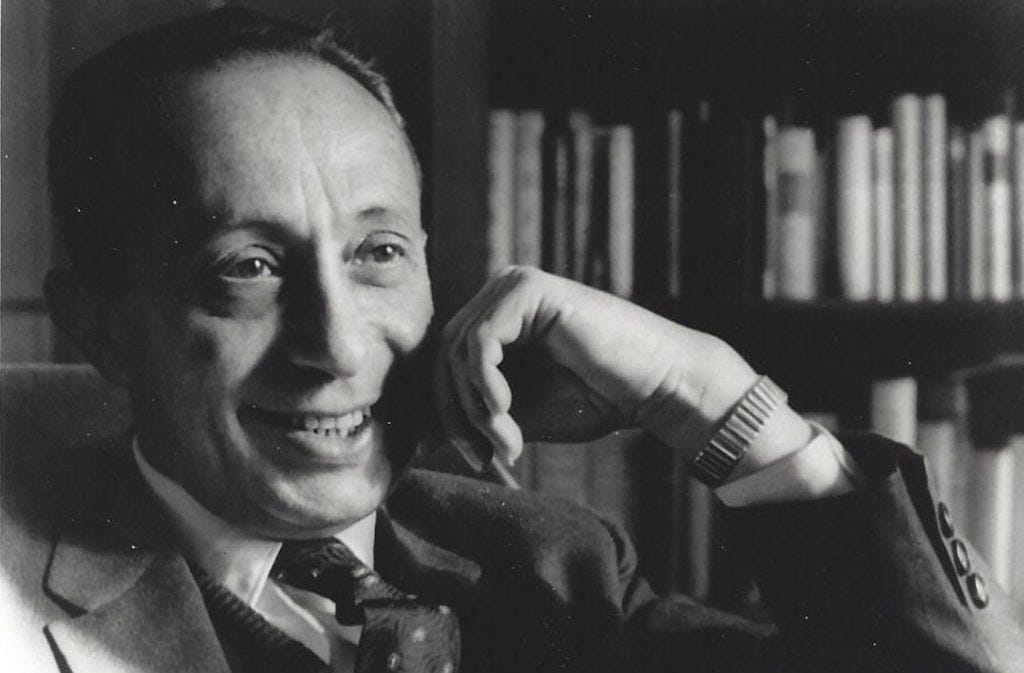

I vividly remember being a postgraduate philosophy student and encountering what became a threshold concept for me. I was in a rented flat, which I shared with my then-girlfriend, now wife, and was lying in bed reading The Phenomenon of Life by the German-Jewish philosopher Hans Jonas.

Jonas is well known for his groundbreaking ethical reflections on technology and his pioneering interpretation of ancient Gnosticism. For me, though, the light-bulb moment I had courtesy of Jonas’ thinking was related to neither of these topics. Instead, the threshold concept was the notion of teleology – in particular, the idea that all living beings are characterized by teleology in a distinct way.

So what is this idea, and why do I think it’s so important? To answer these questions, we need to look, first of all, at two other ideas which are far more prevalent.

Purposeful by design

Image: Has Jonas, hansjonasinstitut.de

The first of these competing ideas is the more ancient. It’s the notion that living beings, and indeed everything that exists, are products of a creator-deity. On this view, whales, cats, oak trees, and people are all the way they are simply because they were made that way.

This view is teleological in that it takes each living being to be defined by purpose. But it’s not Jonas’ understanding of living beings, and so not the one that became my threshold concept.

It was, however, probably the most widespread understanding of living beings from late antiquity through to the nineteenth century, and plenty of people in the West and beyond would subscribe to it still. Nevertheless, it was displaced as the orthodox Western view of living beings by the second of these two ideas.

Chance and necessity

In the contemporary Western world, the established understanding of living beings is the mechanistic interpretation. No one believes that living beings are literally mechanisms or machines, of course, but the orthodox view amongst contemporary philosophers and scientists is that living beings are the same as machines in fundamental respects.

The mechanistic view of life first came to prominence during the seventeenth century. This was a consequence of the invention of increasingly intricate mechanisms such as automata and figurine clocks. These new machines moved with such lifelike delicacy and precision that it became possible to think that living beings operated in just the same way.

Indeed, in the 1640s, the great French philosopher René Descartes famously argued that animals could be understood as mere automata, their calls and gestures being no more purposeful than the movements of wheels and pulleys.

A century later, the philosopher Julien Offray de La Mettrie extended Descartes’ argument to human beings in his classic and hugely controversial work L’Homme Machine. It was the arrival of the theory of evolution by natural selection, however, that would prove decisive in popularising Descartes and La Mettrie’s position. With a compelling naturalistic theory of change and development to hand, it became easy to argue that living beings are little more than moving parts driven by forces of nature.

According to this view, the organism – any organism – can be viewed as a product of the genome, which is itself a result of the evolutionary process. Put another way: natural selection picks winners according to a remorseless logic of environmental fitness, and those winning organisms are themselves simply produced according to a genetic blueprint mutating at random.

This is the complete, the total mechanistic view of living beings. As the biologist Jacques Monod claimed, with terrifying finality: “Anything can be reduced to simple, obvious mechanistic interactions. The cell is a machine. The animal is a machine. Man is a machine”.

But was Monod right?

Two kinds of teleology

What Descartes, La Mettrie, Monod, and a host of contemporary philosophers and scientists miss is that there is another, more appealing interpretation of living beings. That is to say, the choice is not just between teleology by design and the mechanistic interpretation of life. There’s a third option.

It’s the idea that every living being, from an amoeba to a human being, is teleologically constituted – but not because they were designed that way, as the older view had it. Rather, being purposeful is simply what it is to be alive.

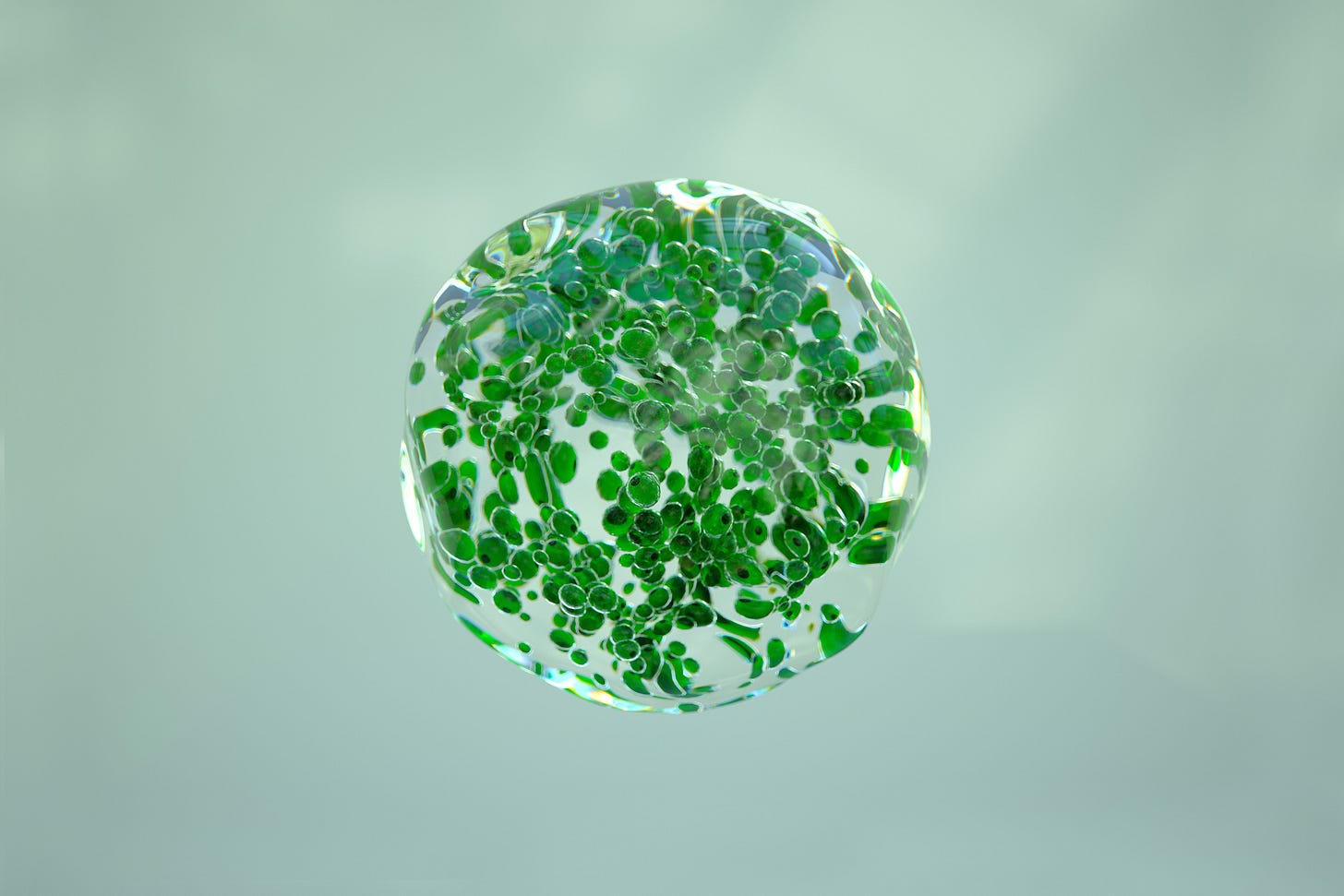

Jonas observes that each living being is teleological in two ways. The first is that they reconstitute themselves in a given form through the metabolic process. In other words, living beings don’t simply drift apart as they excrete matter in a variety of ways, but instead, new matter is absorbed, and the form of the living being maintained. There is a purpose here: the maintenance of a particular form against entropy.

The second teleological dimension of living beings is that they engage with the world to greatly varying degrees. As Jonas puts it, all living beings reach out of themselves in pursuit of their continued existence – whether that’s with refined sense organs or just a rudimentary responsiveness to certain stimuli. Regardless, there’s a kind of purpose present in the organism’s behavior, marking it out as alive.

Taking these two aspects of teleology together, Jonas calls this kind of teleology ‘immanent’ – meaning inherent and within – to distinguish it from the understanding of teleology as a design, which originates in a designer.

At the threshold

When I first encountered this idea, I was dumbstruck. This is the correct view of living beings, I thought, capturing their uniqueness and majesty. The idea changed the way I view the world and so constitutes a threshold concept for me.

Perhaps reading the above, you won’t feel as I did. Perhaps your worldview more closely aligns with the notion that living beings are what they are thanks to a creator-deity, or perhaps you’re persuaded by the mechanistic interpretation.

Perhaps, however, even just a few people reading this will feel as I did. Perhaps your thinking about the particular nature of the living will be changed in a deep and lasting way. Then you, too, will have Jonas to thank for a threshold concept.

Editor’s note: Jonas’s understanding of “immanent teleology” seems to just kick the can down the road. In essence, he agrees that there is the appearance of design in life but just asserts (it seems to me) with a bit of a hand wave, “Well, that’s just what life is like.” That does not seem to tackle the question of why it is like that—the more fundamental and important question.

The belief in teleology as a form of design has not abated since Jonas left us in 1993. If anything, it has strengthened. For an example of this understanding of teleology, I recommend Michael Denton’s The Miracle of Man.

I think the WHY is the origin of it all and is unknowable. We are because we are. For me, evolution (the mechanism) is how G-d (the designer) expresses. Now for my surprising threshold thought. When I encountered this, chlls ran up and down my spine and I said, "I want this on my tombstone." Because it was always the purpose of my life ever since I could remember. It make me cry. I don't care about any deeper purpose because, in this incarnation, I am on Earth as a human being and I have to live the best human life I can. I had NO idea that my obsession with marginalized people and my burning desire to speak about them to the world was anything but just being a product of the 1960s. I had no clue that salvation was even connected to it. When I read this quote, I was flabbergasted.

Here it is:

"I care about this because my faith teaches me that salvation has to do with how I make myself useful to those who have been excluded, marginalized, and cast aside and oppressed in our society" --- Pete Buttigieg