Is It Wrong To Eat An Octopus?

How to develop a sensitivity to sentience.

You might not have seen it on the news, but around the world, protests are taking place against a proposed farm in Spain. The reason for the outcry is the farm’s unique livestock: octopuses.

The worldwide demand for octopus meat is rising, and since catching wild octopuses is failing to meet it, the logical next step is to rear octopuses through aquaculture. Plenty of animal rights campaigners strongly object to the plans, however, claiming that it’s unethical to intensively farm these animals.

The story is politically interesting because of the international condemnation the farm has drawn. More than that, though, it’s philosophically fascinating because the ethical debate turns on the question of sentience.

Legally speaking, the farm would be allowed to rear and slaughter octopuses however it likes because neither Spain nor the European Union has animal welfare legislation covering them.

This is the result of a curious omission: although Spain and the EU both recognize animal sentience in law, invertebrates such as octopuses aren’t included. By contrast, the UK recently extended its animal welfare legislation to cover octopuses, crabs, and lobsters in explicit recognition of their sentience.

Here’s a prompt for all of us to rethink how far sentience is spread throughout the natural world. Are octopuses no different from cows or pigs in this respect? And why does sentience matter so much in the first place?

Why sentience matters

The first thing to note is that sentience isn’t the same thing as intelligence. It’s something much more basic: roughly, having feelings or sensations. So the question of whether a given thing is sentient is to ask whether it can sense or feel.

The second thing to note is that sentience comes in various levels of complexity. In some cases, such as plants, it takes the form of rudimentary responsiveness to stimuli; in some animals (such as mussels), it seems to include a basic capacity for smell. In other animals, it includes complex things like memory and the ability to feel pleasure and pain.

Sentience is often relevant to animal welfare issues, such as the octopus farm, because if an animal is sentient enough to feel pleasure or pain, then this fact has some bearing on how we should treat them.

Of course, the question of how much it matters, morally speaking, is a thorny one. For an animal liberationist like the Australian philosopher Peter Singer, it’s pretty much the only thing that matters: according to Singer, if an animal can feel pain, then harming or killing it for food is morally out of the question.

Other philosophers, following Immanuel Kant, argue instead that it’s acceptable to harm and kill any animal provided that in doing so we don’t become cruel or unfeeling people.

Whichever philosophical position you find persuasive – and there are many more besides – sentience has some ethical relevance. This is why, as we’ve seen, plenty of countries recognize the sentience of vertebrate animals that are known to feel pain, such as cats and dogs. What about octopuses, though?

The science of sentience

Now, here’s what’s fascinating: lots of people find the question of whether octopuses are sentient absurd – but for totally opposite reasons.

For some people – myself included – it’s just obvious that octopuses are sentient and bizarre to suggest otherwise. Other people, however, are certain that octopuses aren’t sentient, citing their lack of a centralized nervous system.

Scientific research claims to be able to help us here; however, as in recent decades, scientists have explored the question through experimental means.

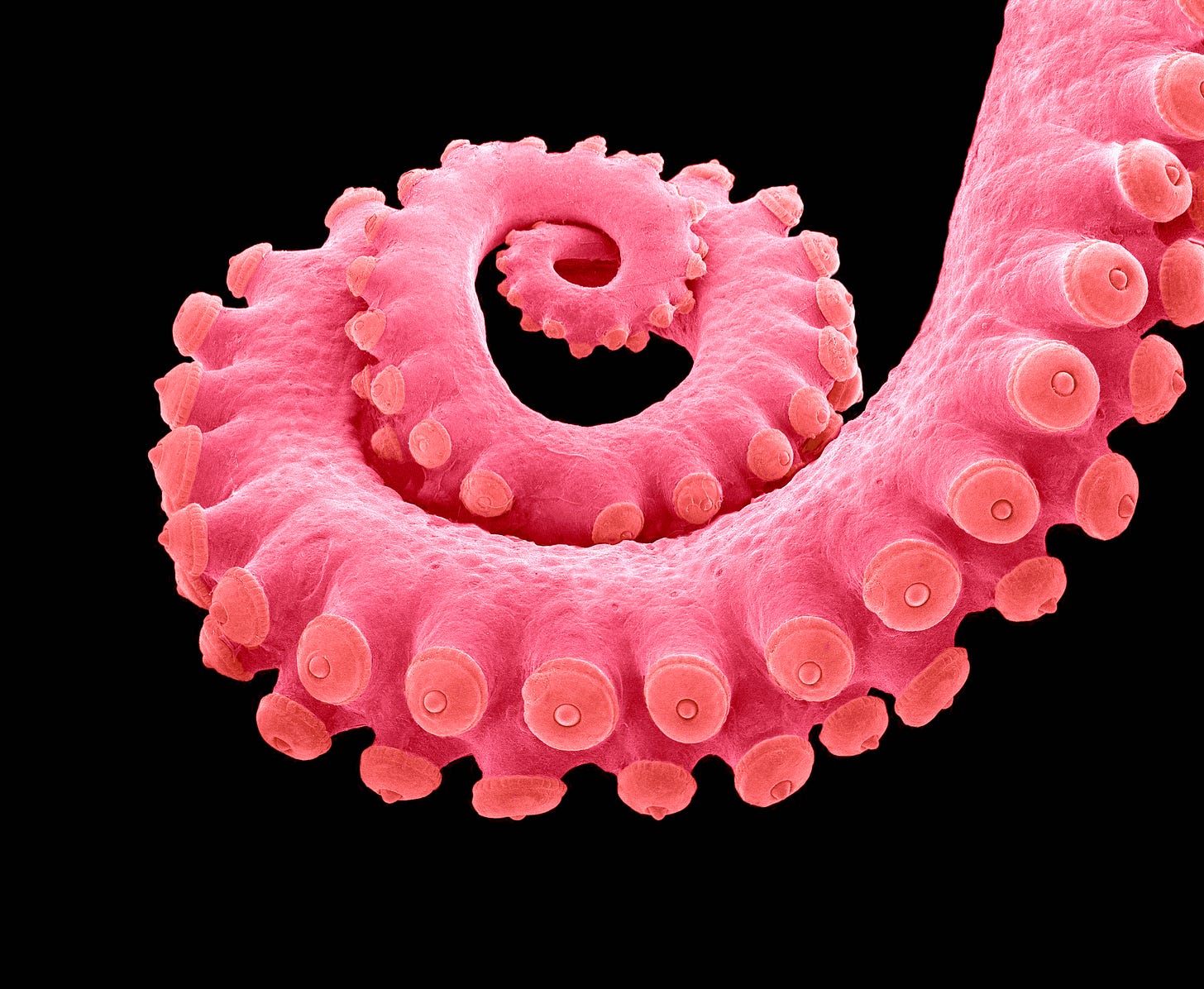

A landmark report produced by the London School of Economics in 2021 synthesized over 300 academic journal articles that looked for evidence of various traits of sentience in octopuses. The latter ranged from physiological criteria, like the possession of integrative brain regions, to behavioral criteria, such as the capacity for associative learning. On this basis, the authors concluded that “there is very strong evidence of sentience in octopods.”

For those people who think that octopuses aren’t sentient, this conclusion will hopefully convince them otherwise. To that extent, believers in octopus sentience should welcome the report.

Even so, there’s something unsatisfactory about approaching the issue in this way. Trying to prove octopus sentience scientifically just seems theoretically mistaken. After all, isn’t sentience accounted for in a more fundamental way?

The non-problem of animal minds

If you share this suspicion, it might be because the science relies on a pre-scientific intuition.

This, in short, is Helmuth Plessner’s argument. Plessner was a German-Jewish philosopher with a background in medicine and zoology. He wrote compellingly on the nature of human and non-human life, partly thanks to this broad education.

In his 1928 masterpiece, Levels of Organic Life and the Human, Plessner argued that most philosophical and scientific approaches to living beings remained negatively indebted to the Enlightenment philosophy of René Descartes.

According to Descartes, the world is comprised of two basic ‘substances,’ or kinds of stuff: there’s matter, and there’s mind. Descartes believed that human beings were comprised of both substances, mind, and matter. Everything else on Earth, however, was made of matter alone – including animals, which Descartes likened to mere automata or robotic models.

Plessner believes that Descartes’ wrongheaded view has cast a long shadow over modern thought. It has encouraged us to theoretically conceive of sentience as belonging solely to humans unless proven otherwise. Hence, we’ve only gradually come to acknowledge the sentience of vertebrates and are now split over the sentience of invertebrates like octopuses, looking to science for definitive answers.

The problem is that the Cartesian position doesn’t account for how we actually perceive sentience. Rather, Plessner says, as we go about our lives, we automatically interpret things as either living or unliving. The latter are objects that are self-contained—that just reside. Think of a book which sits there, neither changing nor acting of its own accord. Even if we think of a mechanized object, like an aerial drone, we don’t perceive its movement as coming from any inner impulse.

This is wholly different from how we perceive the living, animals in particular. Take a bird since it contrasts nicely with the drone. The movement of the bird in flight, its behavior, its responsiveness to the world, all point toward what Plessner calls an inner core or center. It’s not a physical point that we could touch but a ‘phenomenal’ center that we perceive as the ‘inside’ of the bird, a core from which everything it does flows. Animals have it; books and drones do not.

Sentience is revealed to us in our perception of this phenomenal core. We detect it when a dog trots up to us wagging its tail – or when one growls at us and bares its teeth. On this basis, scientific experimentation and measurement can try to identify physical correlates of such sentience – but the discovery of sentience itself is something prior, more fundamental, and intuited.

Back to life

How, then, do we know that octopuses are sentient?

Plessner’s answer is: in just the same way as we know dogs are sentient: by discovering their sentience in our perception of them. We see it in the octopus’ movement, its responsiveness to the world, and its expressiveness, all of which appear as outward manifestations of an inner and aware core. It’s my belief that this idea, taken seriously, could have positive consequences for human-animal relations.

In societal terms, the debate over animal sentience and welfare stands to benefit. First, We could focus on the fact that all animals – cows, chickens, bees, and octopuses – show up to us in the same way: as centers of life reaching out to the world.

This would settle the basic question of animal sentience. We would no longer ask which animals are sentient but instead how intelligent and how perceptive each species of animal is. Does a given animal have a long-term memory? Can it feel pain? It’s here that scientific research comes back into play. If it’s right in the case of octopuses, then they are highly perceptive and intelligent indeed – ranking right alongside terrestrial vertebrates like pigs.

The ethical demands of sentience

The really tricky question, of course, is what this would ethically entail: the moral implications of recognizing sentience across the living world are vast.

We can confidently say that octopuses, fish, crabs, and lobsters would have to be given the same ethical consideration – whatever that may be – as we currently give to terrestrial vertebrates. If there’s little difference in how intelligent and feeling these species are, then it seems unreasonable to ethically discriminate between them. So, for a simple example of what this consistency would mean, a country like Spain should surely extend its legislation dictating that pigs be humanely reared and slaughtered to octopuses as well.

There’s a more profound question at hand, however. This is how each of us should respond to the fact that whatever we eat – lettuce or lobsters – we’re consuming sentient beings. Humans can’t survive on inorganic matter, so what should we do?

There are no easy ways to answer this question. However, a clue for how to proceed lies again, I think, in the idea of levels of sentience. This notion modifies our preferred moral philosophy, whatever it happens to currently be.

For instance, a utilitarian like Singer would have to acknowledge that even eating a lettuce entails a sentient being losing out. As such, they would presumably have to draw a line in the sand between sentient beings that can’t feel pain versus those that can. Since plants possess only basic responsiveness to stimuli, there is a great qualitative difference between eating them and eating an animal with the capacity for such feelings.

Animals like mussels and oysters, which possess only very basic senses, are presumably counted with the former rather than the latter.

The idea of levels of sentience is also helpful for people whose ethical beliefs center on cultivating virtues such as kindness. If we wish to be kind rather than cruel people, then, again, a general rule of thumb would be to eat plants as well as animals that can’t feel pain.

If we did choose to eat animals that can feel pain, then it surely would be kindest to avoid intensive, factory-farmed meat and instead eat animals that had enjoyed a wild and free life before being killed as quickly as possible. This would be the difference between eating farmed octopus and catching it straight from the sea.

In addition, we could try to cultivate the virtue of gratitude in whatever we ate. We could be grateful for the sliver of sentience that is taken whenever we kill a plant to eat it. We would be more thankful still if we chose to eat animals, in particular those that can feel pain, in recognition of what we’ve taken from them. Either way, this would be conducive to a humbler existence, one that was more respectful of the sentient life that is constantly extinguished in order to continue our own.

Sensitivity to sentience

There’s a final implication of Plessner’s thoughts on sentience, though – one that’s less ethical and perhaps more spiritual. It’s that his thought encourages us to shed inherited and unexamined ideas of life by returning to the world of perception.

That is to say, the assumptions of early modern science and philosophy, which continue to influence our theoretical conception of the world, would be put in check by a renewed focus on the world in which we actually move and breathe. We would no longer expand the circle of sentience to other life forms only begrudgingly but instead do so willingly by accepting the intuitive evidence of sentience in the perception of life.

We would open our eyes to find ourselves surrounded by feeling, sensing, living nature – part of a web of human and non-human sentience spreading across the kingdom of life, and to which, truth be told, we belonged all along.

Call it a greater sensitivity to sentience.

Hi Lewis, I was wondering if Peter Singer would be ok with eating any sentient being as long as it didn't suffer (e.g: anesthetized).