Heisenberg, Tao and the Unbreakable One

The more closely we examine the physical world, the more it seems to recede from us. Our mistake is trying to grasp the whole by only looking at a part.

We've all heard it said that "the whole is greater than the sum of its parts." But what if the reality is even greater than that – what if there really are no parts to begin with and that most mistakes that we make in trying to understand the nature of things result from an inability to accurately perceive reality for what it truly is?

One of the most fascinating aspects of Quantum Mechanics is known as Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle. The principle essentially states that there is a limit to the precision with which we can know "complementary physical variables" of a particle, such as position and momentum. The more we know about the one, the less we seem to know about the other. It almost appears that the very act of measurement somehow affects the particle and makes it less knowable.

One of the fathers of Quantum Physics, Neils Bohr, once made the surprising observation that "it is a mistake to think that a particle ever existed prior to our measurement...isolated material particles are abstractions."

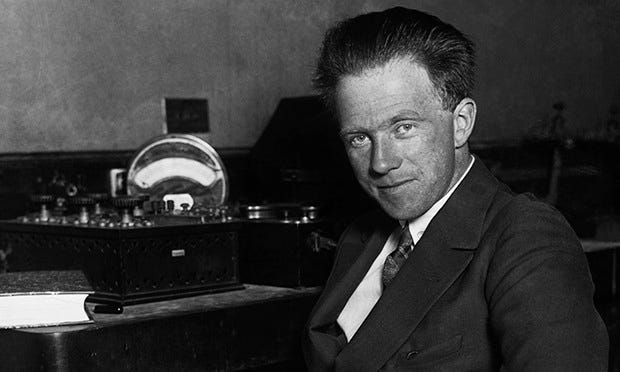

So if the particle didn't exist before we measured it, what exactly was it before? German theoretical physicist Werner Heisenberg said it was "a strange kind of physical reality just in the middle between possibility and reality." Oddly, prior to measurement, the particle is said to exist everywhere, in a state of "superposition" – up until the time that we attempt to locate it – at which point we can discern certain qualities that it has but not others.

Some scientists go so far as to suggest that these particles don't exist at all. In an essay entitled "Particles Do Not Exist" by physicist Paul Davies, we find that "the particle concept is nebulous and ideally it should be abandoned completely." British astrophysicist John Gribbin agrees. He writes that "we call those objects particles, for want of a better name, what they really are, we do not know… the particle concept is simply a crutch ordinary mortals can use to help them toward an understanding of mathematical laws."

Perhaps we can posit that the reason for the strange particle phenomena and our inability to describe what they are is a consequence of attempting to reduce an unbroken whole – a unity – into parts. Particles are what we believe we perceive when we try to grasp a portion of the whole and hold on to it. Fortunately or unfortunately, this is impossible – and always will be. To truly apprehend the All, we would need to be that All ourselves. A subunit can never discern the all-encompassing totality of the whole.

To truly apprehend the All, we would need to be that All ourselves. A subunit can never discern the all-encompassing totality of the whole.

The British writer and theologian C.S. Lewis has suggested that a similar dynamic is at play with spirituality and morality in general. Any attempt to isolate any particular facet of morality or goodness from the comprehensive unity it came from will ultimately be self-defeating. Much as trying to make sense of one square millimeter of the Mona Lisa would limit our ability to see "the big picture," so would cherry-picking certain preferred moral practices thwart our appreciation of the context from which they were drawn. In "The Abolition of Man," Lewis referred to this comprehensive morality as "the Tao."

"This thing which I have called for convenience the Tao, and which others may call Natural Law or Traditional Morality or the First Principles of Practical Reason or the First Platitudes, is not one of a series of possible systems of value. It is the sole source of all value judgments. If it is rejected, all value is rejected. If any value retained, it is retained. The effort to refute it and raise a new system of value in its place is self-contradictory."

According to Lewis, there is no way for this moral system to evolve, and any effort made to critique it can only be attempted using elements drawn from the system itself. Once we declare a thing to be right or wrong we are tacitly admitting the existence of an actual right and wrong by which we are able to judge that thing – indeed the terms "right" and wrong" themselves are borrowed directly from the "Tao." Only a full-scale rejection of the system (of the very notions of right and wrong) could suffice to dislodge any particular aspect of it. The only disadvantage of that approach is the necessity of forfeiting the ability to make moral declarations of any sort. As he wrote:

"There has never been, and never will be, a radically new judgment of value in the history of the world. What purport to be new systems or (as they now call them) 'ideologies', all consist of fragments from the Tao itself, arbitrarily wrenched from their context in the whole and then swollen to madness in their isolation, yet still owing to the Tao and to it alone such validity as they possess."

In Judaic tradition, this concept finds expression in the practice of the twice-daily recitation of the "Shema" prayer – which is essentially a meditation on the concept of the ultimate oneness of the Creator. The first line is said while the practitioner covers his or her eyes with the right hand – an indication that it's necessary to stop seeing with the eyes and rather with the mind's eye to block out the apparent (and false) perception of the multifariousness of the universe in favor of the true, unified oneness that it is.

From the search for a "Unified Field Theory" to the creation of the UN to the emergence of holistic medicine, human beings possess a natural drive towards and craving for unity. Perhaps this drive is indicative of an innate ability – to divine within complex systems the true, One, indivisible whole that underpins reality itself.