God Save These Bones

Denim-clad Bibles, Denim-clad Directors, and the Wild, Wild West of Acting Theory.

Image: spieltimes.com

When I pitched this essay, the editor responded, “I like it. Can you do me a favor and read Ecclesiastes?” I responded, “I can certainly try.”

And that is how I found myself, on a Saturday afternoon, looking at a site called “Bible Gateway,” which I quickly decided was a site I did not want to spend a Saturday afternoon on, lest a spiritual gateway open up right before I had to get dressed to go out to dinner. I had thought that I had taken a copy of the Bible with me when we were cleaning out my grandmother’s attic and then remembered that the one copy was bound in a denim-like material. Past me didn’t want the honky tonk holy book, and present me is very mad at past me for that decision.

I spent three days telling myself that I would buy a copy of the Bible on my way to or from work and then read Ecclesiastes. I didn’t; it didn’t feel right to abandon the Jible (Jean Bible) like that. So I read Ecclesiastes eventually on my phone, holding my partner's hand as we rode on the subway on a bright Wednesday morning.

I think that any female writer who spends part of her youth in New York will always take a crack at writing her New York movie, and I can’t imagine that this will not be a scene in mine.

This essay was supposed to be about Wes Anderson, Asteroid City, three little girls playing Macbeth’s witches around a Tupperware full of their mother’s ashes. And it will be. But you know what's in Ecclesiastes? “There is a time to live and a time to die” and a time to write this essay with a lovely meander around the point. There’s also a section that goes “Everything is vanity,” and to that I say, “No comment.”

Much Dreaming and Many Words Are Meaningless

Image: cordeliaaaynaan.blogspot.com

Asteroid City (now on streaming!) is a play within a television broadcast within a movie. Many of Wes Anderson’s movies are layered in similar ways, though this one seems like the most practical, since the ending hinges on the audience being able to see the actors backstage (which is often more interesting than what’s going on onstage). The dominant, and correct, reading of Asteroid City is that it is about grief.

In the play, Asteroid City, which is being staged as part of a television program, Jason Schwartzman’s character has lost his wife and has lost his ability to tell his four children that their mother is dead. Upon arriving in Asteroid City, a dusty, pastel, nuclear-tinged wasteland for his son’s science competition, he tells the children they’re half-orphaned and presents them with a Tupperware of their mother’s ashes.

Schwartzman’s three young daughters bury their mother’s Tupperware in the desert sand next to their motel with the typical aplomb and nonsense rhymes of little girls. They bury her with the hope that she will “come back alive,” a wish I’m sure many of us have privately had.

And then the camera darts down into the sand, and the youngest daughter peers over into the lens. She says, “God save these bones.”

At the same time, behind the scenes, Schwartzman, in his second character as the actor in the golden 1950s of New York theater, struggles with a moment in the play where the character burns his hand on a hot plate. He struggles with the moment in his audition, and he struggles with it during the performance. He dashes offstage, sits before the director, and says “I don’t understand the play.” The director (Adrien Brody, wearing a pair of jeans not unlike the Bible that got away says “Doesn’t matter, just keep telling the story.”

Both of those moments punched me in the face, which I mean to be a complimentary statement. I sniffled a bit at “God save these bones,” remembering the earnest pleas to something larger than myself that I had made at such an age, although I’m sure my more frequent ask of “Can I have straight hair, please” was not nearly as affecting. When I heard “Doesn’t matter, just keep telling the story,” I paused the movie and sat with a half-chewed apricot in my mouth until I felt composed enough to chew and press play.

Again I Saw Something Meaningless Under the Sun

I went into college thinking I wanted to be an actor and was reasonably successful until I decided to switch to the much more stable and lucrative job of being a writer. I studied lots of acting methods, some in practice and some in theory, and I’ve taken writing course after writing course. In all that time, pre-college and post-college too, I have never had anyone respond to my saying “I don’t understand the play” with “It doesn’t matter.”

Understanding is in the foundation of modern theater. Most of the acting methods people study are based on as deep an understanding of the character as possible, sometimes deeper than I think necessary. I learned very early on (although I kept “forgetting”) that the answer to the question “why is your character doing that” should not be “the playwright wrote it that way.” After switching to playwriting, I have also learned that “why is the character doing that” is not a question that most people like to be answered with “I wrote it that way.”

And so, with one line from a director named Schubert Green, Wes Anderson reframed decades of acting theory and four years of my education. It doesn’t matter if you understand it or not. How magnificent.

That line is more than a reflection on modern acting theory, though; it’s an answer to two of the biggest pleas in the movie. A running joke is that the girls are Episcopalian because of their mother, so presumably the God they talk to is the Christian one. But at the same time, they just tried to bippity boppity boo their mother back to life, so perhaps they’re not talking to some concrete theological entity.

But Schwartzman is talking to God, or at least as close to God as an actor can get, which is the director. For some actors, they are their own God, but I digress. And for once, God answers. (This is where the metaphor breaks down- directors usually answer their actors. Sometimes they say “go ask the playwright,” which is about when I wish they would stop answering.)

The director’s response, “Doesn’t matter, just keep telling the story,” is an answer in the play as well as the production. The girls ask for their mother to be cared for in a place they can’t see, the actor asks for the place he can’t see to become visible. The surrogate God of the theater won’t give material satisfaction to either of them. The girls won’t know during their lives if God saved those bones or not, and Schwartzman needs to go back onstage regardless of whether he understands or not. Life goes on, whether you get it or not, whether you see it or not, whether your prayers are answered or not.

And so the girls learn the hardest lesson a person can learn, and Schwartzman learns the hardest lesson an actor can learn (and should learn, if you ask me). You’re not in charge, the director says, you don’t need to understand. You just need to keep on keeping on.

There is Nothing New Under The Sun

So. A summer Wednesday morning in New York. The man next to me is playing Candy Crush, My partner is sleeping on my other side. I have forgotten all about the bagel I am going to buy for breakfast because I am reading Ecclesiastes. It still feels wrong to be reading it on my phone, like a betrayal of the Canadian tuxedo Bible I could have had.

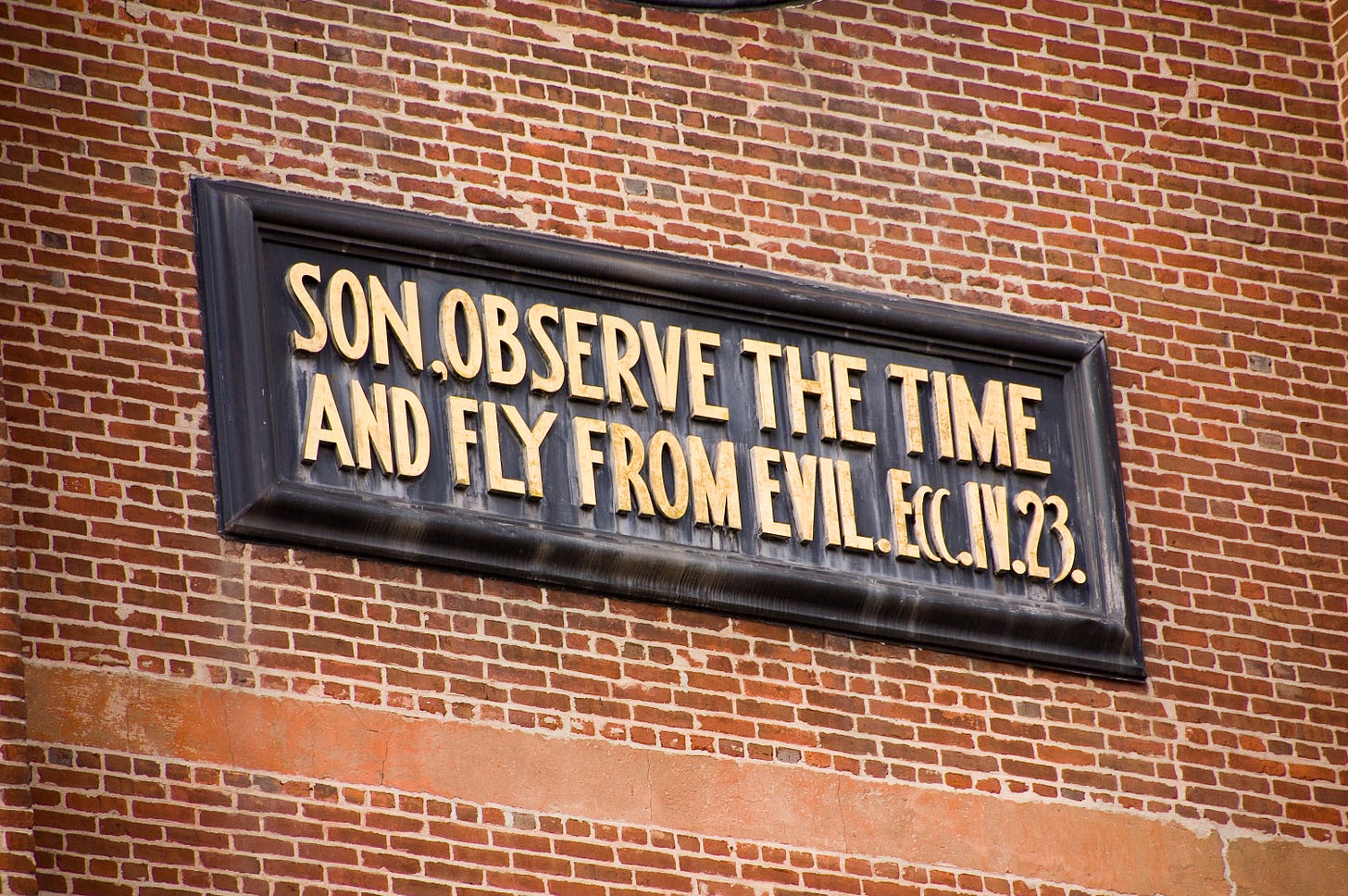

We were somewhere over Brooklyn when I read “He hath made everything beautiful in his time, also he hath set the world in their heart, so that no man can find out the work that God maketh from the beginning to the end.” “Oh,” I thought. “I get why the editor wanted me to read this.”

Ecclesiastes, which I will probably never spell right on the first try, is a portion of the Hebrew Bible that answers the classic question of “what is the point of any and all of this?” The answer, unfortunately, is the divine equivalent of shrugging and saying “I guess you’ll never know.” We are meant to live our lives, revel in the glory of the world that God has made, and accept that our place means that we will never see what comes after us, but benefit from what came before us. We are finite beings in an infinite world, and it’s best just to thank God for what we have, and not worry about what we won’t.

I often had answers other than “that’s what the playwright wrote” when I was acting, just like I often have more answers than “that’s what I wrote.” But those answers always boiled down to that sentiment, because the writer is what made the character lose their mother or run out of money or join an organized crime ring. “Because that is the way that it is” was always what I wanted to believe about art, allowing it to exist in its own borders outside of my total comprehension. Ecclesiastes was my private Schubert Green, a director sitting before me on an F train telling me that as long as I kept telling stories, it was okay not to fully understand them.

A Time To Search and A Time to Give Up, A Time to Keep and A Time to Throw Away

So I guess there’s two essays here, one on the secondary theme of Asteroid City, and the other on me letting go of years of acting education and existentialism by reading the Bible. If I might be so bold, this is very Wes Anderson of me. Many of his movies (The Grand Budapest Hotel, The Royal Tenenbaums, The French Dispatch, Asteroid City) involve some sort of narrative frame, a story within a story (within a story, even). This allows him to do whatever he wants, as long as it wraps up at the end.

That’s an admirable way of working, I think, and very in line with Asteroid City and Ecclesiastes. See? I told you I’d meander around the point, but I’m here at last. The meaning of the story isn’t nearly as important as the telling. The afterlife isn’t nearly as important as the life that is lived before. The girls’ mother will never come back to life, Jason Schwartzman may never understand the play, I’ll continue to frustrate my creative partners with unsatisfactory answers until I take my last breath.

It’s a trite sentiment, it really is. The journey is always more important than the destination, it’s more important than knowing what the destination is. But for a long time, my artistic instincts seemed shallow, like I was content with an insufficient amount of depth and intellectual rigor. Too bad, I can say now, I have the Bible and Wes Anderson on my side.

OY, talk about navel-gazing. Most human beings seek meaning in their lives. It's a natural human trait. I remember wrestling with existentialism and its premise that life is meaningless. I was in an NYC subway waiting for an F train. I realized that even if everything was meaningless I would naturally assign meaning to things anyway. So, life was not meaningless. The train arrived, I got on it, and I never looked back on that cynical philosophy. Everything is loaded with layers of meaning. That's why we keep on incarnating, so we can get it right. Seriously, who thinks about this stuff past college? I sure don't.