From Space to Spirit: Tagore, Deadheads, and the Infinite Groove {Arts}

The Grateful Dead at 60 and the timeless human quest for connection

Image: Dead and Company, kennethcguizar.pages.dev

Golden Gate Park, the site of the Human Be-In in the 1960s, was once again the location of a musical celebration for the first three days of August to recognize the 60th anniversary of one of the Bay Area’s signature bands, the Grateful Dead. Swarmed with deadheads, the current incarnation of the group, Dead & Company, performed for three nights, but this was not just melodic reverie; if we consider the ideas of Bengali poet and Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore, it was a return to true religion.

Tagore’s Religion of Man

Invited to give the Hibbert Lectures at Oxford in 1930, Tagore spoke on what he termed “The Religion of Man.” Tagore suggests that to be human is to live as an individual with unique experiences and thoughts, inherently connected to a greater collective existence. We are unlike the animals, who live forever in the now, whose interests are guided only by their physical needs and seeking ways to make the world meet them.

This is not to say that humans are not animals. We are and we have animal needs, urges, and desires which are often foiled by the world. And yet when we look at the universe, we see awesome power in the sun, storms, wind, lightning, and so much else around us. There are natural forces that are too strong for us to harness, so immature humanity begins its religious journey by worshipping the power of nature. Our wants are purely physical, but insufficient to fully satisfy us. The power of nature is greater, so we create gods of power and pray to them so that we too might partake of their strength, a power which is beyond us.

But once we create a civilization capable of sustaining an economy that meets our basic needs without exhausting our time, humanity's most profound change occurs. With our leisure, we begin to think deeply about the power of the universe. These thoughts proceed in two directions. First, we become skilled at quantifying and modeling the way the universe works and how the power is predictable. This is science, and it gives us truths of nature.

But second, we think about ourselves thinking about nature. When we look inward instead of outward, we ask different questions. Now, we want to know who we are, what we could be, and what connects us beyond ourselves. We turn to questions of values. We want to understand not just the accidental that we have experienced, but the necessary, the eternal, the universal. The infinite is surely a part of our scientific questioning of the universe, but it becomes transcendental when we apply it to ourselves.

“We have our eyes, which relate to us the vision of the physical universe. We also have an inner faculty of our own, which helps us to find our relationship with the supreme self of man, the universe of personality. This faculty is our luminous imagination, which in its higher stage is special to man. It offers us that vision of wholeness which, for the biological necessity of physical survival, is superfluous; its purpose is to arouse in us the sense of perfection which is our true sense of immortality.”

The truly religious is our ability to move from our limited, finite existence to contemplate the limitless, the infinite, those truths that connect our individuality to the universal Man, the Supreme Man, the human collectivity in whose image we are created and whose truths reside in all of us. In moving from naïve idolatry to sophisticated religion, we moved from worship of power in the now to values in the infinite.

The Music Maker

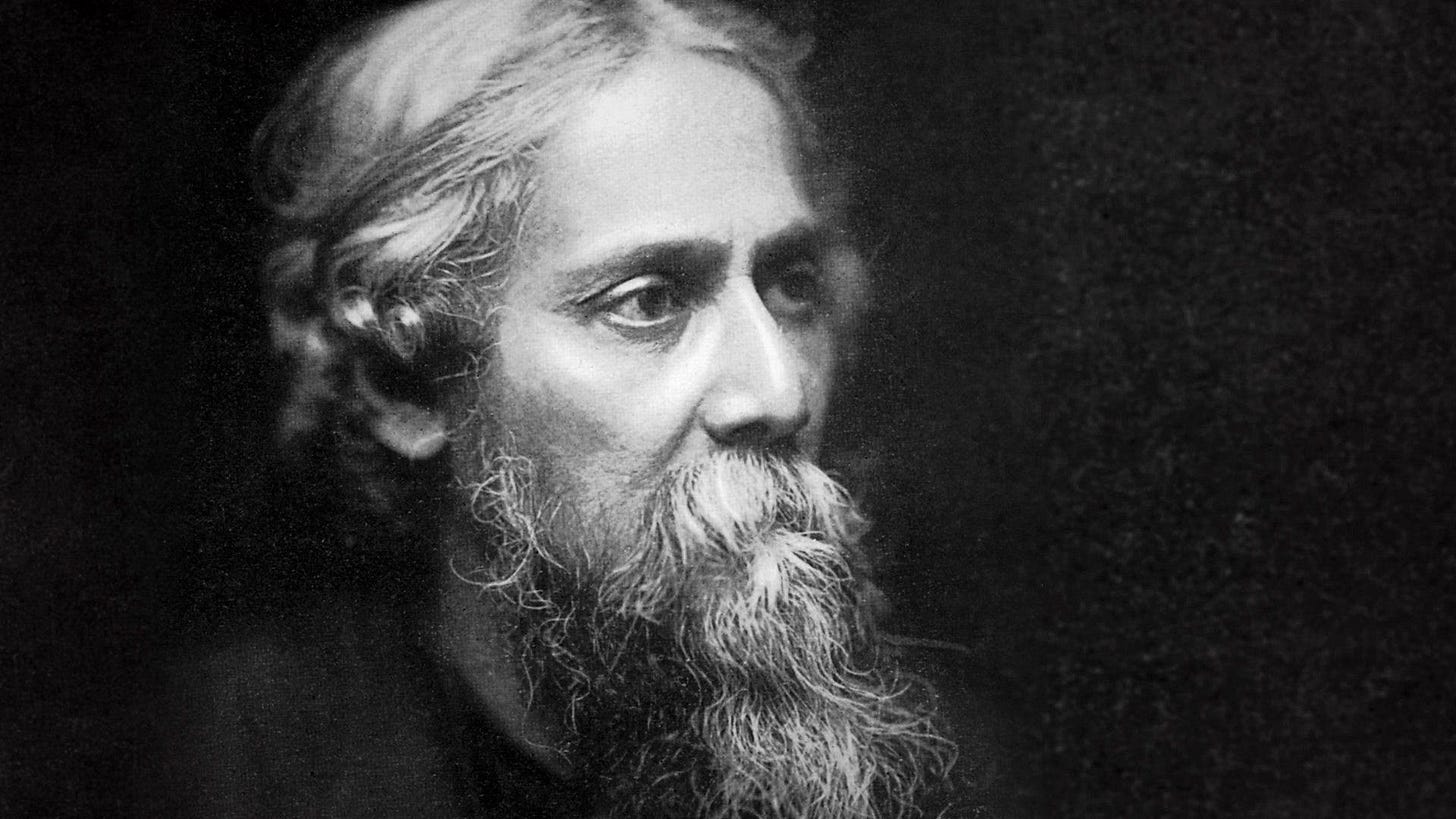

Image: Rabindranath Tagore, ar.inspiredpencil.com

But Tagore has noticed that modern people have reverted. Leisure is needed to provide us with the space to extend ourselves beyond ourselves, to have the chance to strip away the materialistic façade that seems to dominate the minutiae of day-to-day existence and instead launch ourselves into the deeper regions of our minds where we can seek out the profundity of that which connects us to each other and to the universe as a whole.

Yet, it is precisely this leisure that we have eliminated in our search for ever greater physical comforts in the present and a sense that the work of the mind that is not geared toward material reward. There are thoughts of wise people who help us access these greater truths, but we see studying and meditating on their words as a waste of time. We no longer take heed of the prophet out of obsession with the profit.

As a result, wealth and comfort have caused us to turn our backs on the progress we made. Our religion has once again become focused on mere power because our interests are once again solely on the material in the now.

But there is one place that the door to true religion still remains open to us…music. As a young man, Tagore explored a range of religions from Hinduism and Buddhism to monotheistic traditions. He tried hard to find the Divine in the services and texts they held sacred. But his mind was truly opened when he heard a beggar who belonged to the Baül sect in Bengal singing a devotional song. It was not a hymn, a practiced prayer that is expected to be performed in a prescribed way.

Instead, it was an authentic improvisational artistic act of devotion and spiritual desire. “What struck me in this simple song was a religious expression that was neither grossly concrete, full of crude details, nor metaphysical in its transcendentalism. At the same time, it was alive with an emotional sincerity. It spoke of an intense yearning of the heart for the divine which is in Man.”

Music, Tagore understood, is capable of touching the human soul directly. “The difference between the notes as mere facts of sound and music as a truth of expression is immense. For music, though it comprehends a limited number of notes, yet represents the infinite…In music, man is revealed.”

That musical revelation became Tagore's life’s work. Tagore is not only a celebrated poet but also a composer who has written, among other works, the national anthems of Bangladesh, India, and Sri Lanka.

The Music Plays the Band

Image: allthatsinteresting.com

That approach to music as revealing humanity itself through the playing is precisely what is being celebrated in the six decades of the various incarnations of the Grateful Dead. They began as a rhythm and blues group playing the danceable hits of the day. They had a problem with the structure of the songs they performed, specifically, the songs ended. The song would be over, but the band would not be done playing it. They were not ones to be told what to do, even by the songs they performed. Famously, after their first gig at a pizza parlor, the manager said disparagingly when they were done that they would never make it because they were “too weird.”

That weirdness would find a home with Ken Kesey’s band of Merry Pranksters and their Acid Tests. Kesey arranged an open event full of possibility, but with no expectations. The band, for example, could play or not play. The key was for everything to arise organically, for the environment to cause the action, and the action to shape the environment. Nothing was to be forced, but to be allowed to reveal itself, no matter how strange or unexpected, indeed, especially that which was strange and unexpected.

This became the touchstone of the Grateful Dead and the jamband culture they launched. No one was to be in charge, no consciousness dominating the scene, but everyone was open to the influences of the present to allow it to shape the playing, which then, in a feedback loop, shaped the consciousnesses of the audience and players.

In doing so, magic could happen. Spontaneous composition could occur. New riffs and even novel elements that would become songs or parts of songs would appear, not because any particular person intentionally set out to write them, but it would instead blossom out of the fertile soil of mutual humanity, which was the interaction of the players among themselves and with those in the audience.

Early on, the band left large expanses of musical real estate for this to occur. In later years, a section referred to as “Space” would be left for sonic exploration in the middle of the second set. But the point of it was to allow for a place where the mutual interactivity of human minds allowed for something transcendent to possibly occur, for the sort of revealing of humanity that Tagore described.

And that is why tens of thousands of tie-dyed revelers have gathered once again in San Francisco, much as they did in the 1960s. Is there an animal element to it, a pure physical pleasure? Absolutely. But what they seek is something more interesting and profound, they come to be a part of the unity that seeks the essence of humanity in the sort of artistic creation that Rabindranath Tagore showed us is capable of connecting us to the divine, to reveal the deep truths we seek, the limitlessness that can come from the limited notes when they become music and both express and touch our souls.

![Acid Tests: How The Merry Pranksters Gave LSD To America [Photos] Acid Tests: How The Merry Pranksters Gave LSD To America [Photos]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!M4Ki!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb556f178-4ccd-484b-b858-f016bbf53b89_900x639.jpeg)

I share the esthetic and ecstatic view of music to lift the human spirit to Something greater than the self. I have had that experience at many concerts. For me, The Band did that. I felt the Oneness of it all and the complete physical and spiritual joy. But there is one thing I did NOT experience, thank G-d! I did NOT ever experience the Supreme MAN. Because G-d is not a male. G-d has no gender at all. If G-d did have a gender, G-d would not be G-d.

“We thought of life by analogy with a journey, a pilgrimage, which had a serious purpose at the end, and the thing was to get to that end, success or whatever it is, maybe heaven after you’re [grateful] dead. But we missed the point the whole way along. It was a musical thing and you were supposed to sing or to dance while the music was being played.” ~Alan Watts