Fish Do Not Exist

The odd clash between instinct and science.

Carol Kaesuk Yoon has always loved fish, and that poses a unique problem in her line of work. It’s not a dietary problem, an animal rights problem, or anything like that. It’s actually more of an existential problem because, within Yoon’s chosen field, fish simply do not exist.

Dr. Yoon is an evolutionary biologist, and she has a special gift for making complex scientific ideas accessible. When she decided to write a book about “folk taxonomies”—the ways that various cultures around the world and throughout history have classified living things—she expected to find plenty of strange and confused ideas that would all be cleared up by the light of modern science. And strange ideas she found indeed, but none quite as strange as those of modern science itself.

In her book, Naming Nature: The Clash Between Instinct and Science, Yoon traces the history of scientific taxonomy from its origins with Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus to the startling conclusions of modern cladistics. While Linnaeus relied on a sort of commonsense perception of natural kinds (certainly whales, splashing about all fish-like in the ocean, are a type of fish!), the cladists look to shared evolutionary novelties. The best way to understand the cladistic approach is with an example that Yoon herself provides. Consider the following three animals:

Which two would you say are most closely related? Obviously, this is an easy one – the first two, the salmon and the lungfish, are most similar. They’re shaped similarly; they both live in the water, swim with fins, have scales, and lay eggs. The cow is pretty much the exact opposite. And it is at this moment that the cladist shakes his head with a patronizing chuckle.

The issue, explains the cladist, is that shared morphology is not a good indicator of relatedness. You might look more like your grandfather than your father, but that doesn’t place you closer on the family tree. So too, in our case, it is the evolutionary family tree that matters here, and as strange as it may seem, the lungfish and the cow share the closer branch.

How could that be? At some point in history, the fish family had an awkward breakup. Some of them continued their water-dependent, gill-breathing lifestyle, while others started hanging out in bad neighborhoods and experimenting with air-breathing. Salmon are the modern descendants of that first group, while the rebellious group spawned cows, dogs, humans—and lungfish.

As their name suggests, lungfish are no ordinary fish. They have a sort of lung that they can use to breathe on dry land, as well as internal nostrils and an epiglottis, that flap of skin that keeps food out of your windpipe when you swallow. Despite maintaining many of their fishy qualities, they are closer to the cow’s side of the family tree than the salmon’s.

All of this explains why the cladist rejects the commonsense category of “fish.” If both salmon and lungfish get to be fish because they're descended from a common fishy ancestor, then cows are also fish. For the cladist, you can’t pick and choose. Pruning the fish family tree to exclude cows would be like using the term "my family" to refer to everyone in your family tree except your sister Peggy. It's an arbitrary distinction and not very kind to Peggy.

This is just one example of how the cladists unravel our intuitive view of nature, and Yoon, while accepting the validity of their approach, can't really stomach it. The issue goes beyond her personal affection for what we once called fish. A committed scientist, Yoon argues that our intuitive, fish-filled view of nature is intrinsic to our neurobiology.

In 1980, a twenty-three-year-old man known as “J.B.R.” was checked into London’s National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery following a major seizure. J.B.R. was suffering from a rare encephalitis caused by a herpes infection, and for the next eight months, he slowly regained his faculties until he could perform as well as the average person on standard intelligence tests. But in one area, J.B.R. remained completely disabled—he could not recognize or name living things. As Yoon describes it:

They showed him a picture of a kangaroo, buttercup, camel, and a mushroom… But J.B.R. was stumped. He stared and stared, but although he could see what was there in front of his eyes, could pick out parts of the image, he could not make sense of the whole.

And neurologists began to realize that J.B.R. was just one case among many:

There was Giulietta, a fifty-five-year-old Italian housewife, who, on recovery from her encephalitis, when asked what a bee was, responded, “It is as big as twenty centimeters. It is the same color as grass. It has two paws, and it has teeth.”... And then there was “E.W.,” whose response to nearly every animal she was shown was some variation of, “I have no idea what that is.”

Over time, scientists began to realize that the ability to distinguish between animate and inanimate things is not just a culturally-acquired convention. Observing recurring patterns of brain damage in J.B.R. and the others, neurologists could even localize this faculty to particular regions of the brain. Additionally, Yoon shows that very different cultures carve up the natural world in surprisingly similar ways. It seems that a healthy human is hardwired to see fish, and this led Yoon to an interesting conclusion.

To maintain our connection to nature, our sense of being at home in the living world, we have to retain that intuitive natural vision acquired through millennia of evolution. So what if it's technically wrong? Yoon encourages us to embrace this necessary fiction, even if it means calling a whale a fish.

I had mixed feelings when I finished Yoon’s book. Her conclusion is both pragmatic and sincere, but in a work tackling one of the biggest questions in the philosophy of biology, I was disappointed that Yoon never seemed willing to step outside a rigid materialism. Are our minds really just the evolutionary byproducts of a purely physical universe?

The idea that consciousness is an irreducible element of nature, perhaps the irreducible element, is gaining traction. And if our consciousness is not just a happy accident, then our intuitions become much more than necessary fictions. They may even be our best lens into the nature of reality.

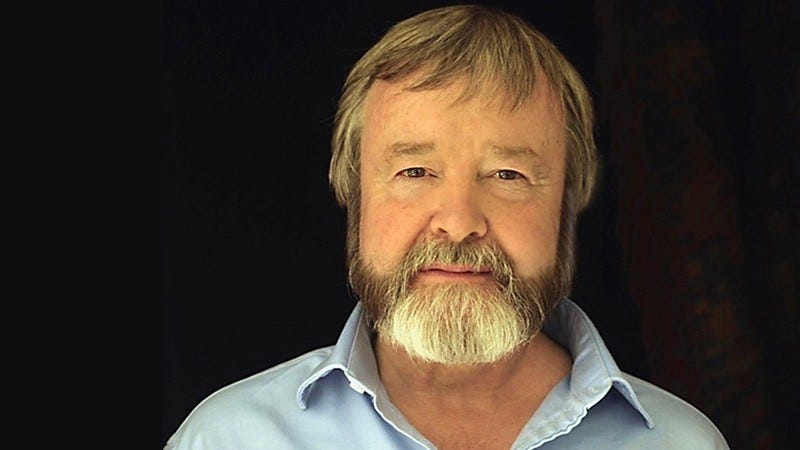

Computer engineer/philosopher Bernardo Kastrup, literary scholar/psychiatrist Iain McGilchrist, and pathologist/complexity theorist Neil Theise are just three of the modern proponents of this view. And though they come from remarkably different backgrounds, they share a notable respect for ancient wisdom traditions; those who long ago recognized what physicist Max Planck would someday become convinced of: “I regard consciousness as fundamental. I regard matter as derivative from consciousness. We cannot get behind consciousness.”

Image: Iain McGilchrist: scientificandmedical.net

Throughout her book, I kept waiting for Yoon to turn to these wisdom traditions for a deeper understanding of the natural world rather than as artifacts of our evolutionary past. As Dr. McGilchrist eloquently observes in his recent book, The Matter With Things: Our Brains, Our Delusions, and the Unmaking of the World:

The Greeks, the Inuit, the Penan, the Chinese, the Indians, the intellects of the Western Middle Ages and of the Renaissance, the Australian Aboriginals, the Romantics, the Navajo, the Romans, the Blackfoot, and the modern Japanese – and countless others – all thought, or think, that there is something speaking to us in nature. If we alone suddenly can’t hear it, in the West in the twenty-first century, how do we know it’s we who are right? (p. 1233)

But what would a consciousness-based taxonomy of nature look like? Luckily enough, we have quite a few. From the early Christian Physiologos to the Talmudic sages’ Perek Shira to the rich bestiary tradition of the Middle Ages, plants and animals are presented according to their meaning, their symbolism, and their moral content. For the authors of these works, our human intuition wasn’t an impediment or even a necessary fiction. On the contrary, it was the only way to sense that “there is something speaking to us in nature” and to hear the unique song of every flower and fish.

I don’t think the cladists are wrong, and I’m happy to accept that there are no fish within the cladistic tree of life. But I also don’t think that our direct experiences and natural intuitions need to play second fiddle. In his new book, Notes on Complexity, Dr. Theise consistently draws on the idea of complementarity to explain this sort of relationship. For physicists, complementarity is perhaps best illustrated in the wave and particle theories of light. These are two contrasting theories of what light is, but each can only explain some aspects of light’s behavior. For a full picture, we need both.

And you don’t need to be a physicist to experience complementarity, argues Theise. We’re all very familiar with our own hands, but get a microscope and zoom in on those sweaty palms, and you’ll soon find that there’s no hand there at all — just a fluid mass of cells! And yet, your hand is not an illusion or an abstraction. In fact, it’s something every bit as real and fundamental as those cells that comprise it. Just as we need the parts to explain the composition of the whole, we need the whole to explain the organization of the parts.

Complementarity allows us to abandon the rigid either/or thinking that often hampers good science. If we take seriously the conclusions of quantum mechanics, ancient contemplative traditions, and our own common sense, then conscious experience seems to be a very real thing, and we can place it alongside modern cladistics as a valuable lens on reality. The fish is alive and well in our experience of nature, even if it melts away under a cladistic lens, like a hand under a microscope. In a world as vast and wondrous as our own, there’s certainly room for both views, and we might even find that they complement one another quite beautifully.

As journalist Miles Kington once observed, “Knowledge is knowing that a tomato is a fruit; wisdom is not putting it in a fruit salad.”

There's something FISHY going on with these cladists. I love this: "Complementarity allows us to abandon the rigid either/or thinking that often hampers good science." AMEN. Zen slap: If it swims like a fish and looks like a fish, and smells like a fish, it must BE a fish. Let's talk about chickens and snakes now.