Feeling the Value of the World

If you were to focus on your surroundings and then try to describe them, how would you go about it?

My guess – because this is what I would do – is that you’d start with the visible objects: people, walls, tables, chairs, etc. Given a moment longer, you might turn to sounds and then smells: the hubbub of other people around you, or the drone of distant traffic; the faint smell of someone’s perfume or food nearby. Only after that, I suspect, might you turn to more abstract concerns: the atmosphere, or vibe, of the place you’re in, for example.

That’s how I would automatically describe my immediate reality. But would that cover everything?

According to the philosopher Max Scheler, this is, in fact, a completely inadequate account. The reason is that it misses something essential to both the world and our existence: something that is there, given the surroundings described above, but which is all too easily overlooked.

That something is value.

The phenomenology of values

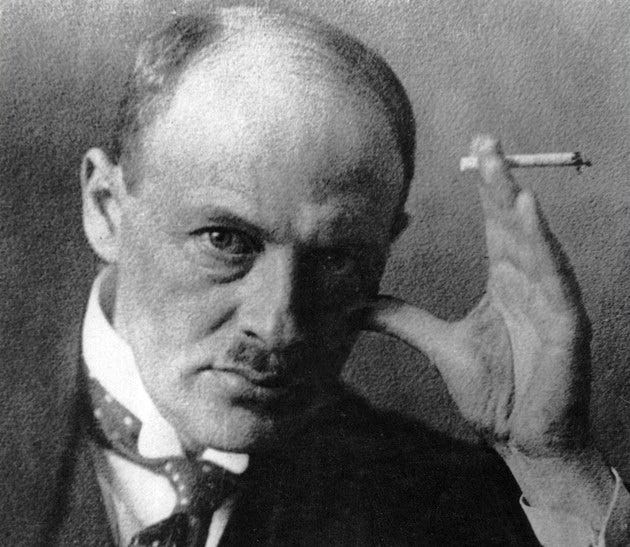

Image: Max Scheler, percyacunhavigil.blogspot.com

Max Scheler was born in 1874 to a German-Jewish family, although he converted to Catholicism as a young man. Scheler initially studied medicine at university, but switched to philosophy and sociology, immersing himself in the world-leading developments that were taking place in those fields in pre-war Germany.

Foremost amongst these developments was the philosophical movement known as phenomenology.

Founded by Edmund Husserl at the turn of the twentieth century, phenomenology represented a breakthrough in modern philosophy. Its self-appointed task was to put philosophy – and by extension, the humanities and social sciences as a whole – on a new, more rigorous footing, by methodically explaining the interrelation of the mind and the world.

For Husserl, our everyday assumption that the world exists independently of the mind is precisely that – an assumption. If we temporarily suspend (though not abandon) our belief in a mind-independent reality, we realise that we can describe the world precisely as it appears. In other words, we can account for the world from a first-person standpoint free of unfounded assumptions and theoretical baggage.

The phenomenological method presented Husserl with a treasure trove of intellectual riches. Over the remaining three decades of his life, he developed theories of time, space, essences, other people, embodiment, and more.

But one thing Husserl failed to adequately explore was the world of value. After all, what matters to us – good and bad, ugly and beautiful, right and wrong – is essential to our lives.

Scheler’s great innovation in phenomenology was turning his attention to this realm, and once understood, it can change the way we reflect on the world.

Love and hate

For Scheler, the world's values are not discovered after we deliberatively survey objects or acts. This is the mistake made by – amongst others – utilitarians, who argue that the goodness of an act is judged by its outcomes. For example, when confronted by a moral conundrum – is it right to steal a loaf of bread if I’m starving? – A utilitarian would try to calculate the positive and negative consequences of the act before arriving at a judgment as to its value.

For Scheler, this misses where a value such as goodness resides in the world. Far from being discovered by rational reflection on something, values are felt in the world itself.

There are two slightly unfamiliar ideas at play here, so let’s take each in turn.

Firstly, there is the idea of value being in something. This is at odds with how I described my immediate surroundings earlier, in that I focused on the perceptible dimensions of objects: visual appearance, sounds, smells, etc. Scheler observes that this is not how the world actually appears. Rather, things in the world manifest as perceptible and beautiful or ugly, good or bad, useful or useless, and so on.

Now, let’s return to our description of our immediate surroundings. If I try to fully capture in words how the world around shows up for me, shorn of any barely-acknowledged theoretical assumptions, I would probably say something like the following: this room is homely yet slightly stuffy; warm and with the faint odour of our evening meal lingering in it. It feels comfortable, but the lack of fresh air in it this evening is somewhat oppressive. The music playing in the background (George Clinton’s funk-rock troupe, Funkadelic) is intoxicating and soulful. The old wooden chair I’m sitting on is worn smooth with decades of use...

You get the picture. The idea is that the world in its appearing is imbued with values through and through: homely, comfortable, oppressive, soulful, and so on. Most of the values presented here are aesthetic, concerned with positive or negative sensory qualities – but we’ll have more to say about moral values shortly.

The second key idea of Scheler’s is that we feel rather than rationally identify value. That is to say, for Scheler, values in the world are emotionally discovered, and most obviously through two powerful emotions: love and hate.

It has to be said that Scheler gives ‘love’ and ‘hate’ idiosyncratic meanings, but the idea is powerful nonetheless. For him, love refers to our open-hearted embrace of the world, which leads us toward the higher values. By contrast, hate is our destructive turning away from the world, which can only lead us toward lower values or the degradation of the higher.

As stances taken on the world, this makes sense to me. But what are these higher and lower values?

From pleasure to holiness

For Scheler, the values of the world range from pleasure to utility, vitality, culture, and ultimately to holiness.

As can be seen from this list, there is a movement from superficiality to profundity: whereas pleasure is limited in both duration and depth of meaning, something that’s culturally foundational or holy can give meaning to an entire society, and last accordingly. Of course, what counts as culturally defining or holy varies from society to society: cows are sacred for Hindus, but merely a source of utility in the West. Scheler’s point, though, is that regardless of what a society puts into those categories, the categories themselves are universal to human beings.

As we’ve seen, for Scheler, we uncover values such as goodness in the world through an emotional-perceptive disposition. Note that these values are not subjective to us, being projected onto the world, nor are they features of the world discoverable through scientific analysis. Rather, they exist in the interrelation of self and world, as the latter manifests to us through the emotional stance we take upon it.

The upshot is that the categories of high and low values Scheler describes are essential components of how we discover the world. They are there even if we focus on a life of pleasure and utility – as modern Western society encourages us to do – and when we discover the higher, we are drawn towards them accordingly.

Seeing the world anew

Scheler’s work has sadly declined in popularity since his death in 1928, not least as a result of its suppression under the Nazi regime – although since Pope John Paul II wrote his doctoral thesis on Scheler, he has found some adherents amongst Catholics.

Nevertheless, if you find the above quite persuasive – as I do – it might just change how you see the world. In fact, the next time you try to describe your surroundings, you may find yourself including goodness, rightness, and beauty amongst the things you can feel in the world.

O my! Scheler got this right! I once had a debate with someone who told me that my view of goodness was not necessarily universal. I normally like to dispense with trying to figure out how many angels dance on the head of a pin. However, THIS discussion was extremely relevant. How do we at least learn to understand other people's values even if we don't share them? Read Return to Laughter, an account of an anthropologist in Africa who learned the hard way that she didn't have to give up her own values while attempting to understand the values of the tribe she was embedded in. Thank you for this. It's so important these days!