Do You Know Your Own Mind?

Freud vs Descartes

Image: sunbehavioral.com

Are you your mind? Do you even know your mind? Do you know what you mean by mind? We can choose to think certain things and seemingly decide to want certain things, but how transparent is our mind to ourselves?

Consider an odd case. A decade ago, Ben, a real rule-follower, was thrown out of an athletic contest for the only time in his life. It was a flag football game, and Ben was playing quarterback. The son of the other coach, who also happened to be the head of the league, was an obnoxious braggart, dirty player, and generally unlikable oaf. As he rushed in, the coach’s son jumped (which was against the rules) as Ben (who had a strong arm from also being a baseball catcher) reached back and threw the football hard. It hit the leaping defender in the groin, causing him to collapse to the ground in pain like a duck shot by a hunter. The referee (who had been in the other coach’s pocket all game, probably because he paid the ref’s salary) immediately ejected Ben for unsportsmanlike conduct.

Since Ben did not have a pattern of trying to harm people or even breaking the rules, Steve (his father) opted not to chastise him or even discuss the event, allowing Ben space to process what had happened. Indeed, the throw went undiscussed for ten years…until last week.

Driving home after work, Steve passed the field where it happened, and the image of that fateful pass popped to mind. Calling Ben when he got home, Steve inquired, “I have never asked this, but did you mean to drill that kid in the crotch?”

Ben’s response, fascinatingly, was “I don’t know.” He explained that, on the one hand, he saw his teammate Hayden sliding along the goal line, giving Ben a low target that would guarantee a touchdown if Ben could keep the ball off the ground, where it could be caught, because the defender could not go through Hayden’s body. That was the direction in which the pass was thrown.

On the other hand, Ben said, guys were complaining on the sideline about the behavior of the jerk on the other team and just before that series of plays he was joking in that context about the famous scene from the movie The Longest Yard in which a player is intentional hit with a football in that uncomfortable region. He said that he remembered seeing Hayden in position to catch a touchdown, but that he could not guarantee that the lingering thought about the movie was not also a motivating factor. In other words, Ben is saying that he does not know what was in his mind or what his true motivation was. But it seems like Ben is the only person who would know. That is…if we know our own mind.

I Think, Therefore I Am

Image: britannica.com

René Descartes famously held that our minds are transparent to us. This is part of his most famous argument, “Cogito ergo sum” or “I think, therefore I am.” Descartes wanted to know what human beings could know with absolute certainty. He asked us to consider the possibility of an evil demon who could control our minds. He is not saying it is true or likely, but asks if it is at least possible. It seems like it is, but in the same way a unicorn is possible.

But if it is possible, then any given thing we think could be fed in by the demon. Being evil, the demon is a liar, thus causing us to think false thoughts about everything, living our lives in an illusory universe. (Yes, this is where the plot from The Matrix comes from, although Keanu Reeves is not in Descartes’ original Latin text—we checked.)

So, it seems that humans cannot know anything with absolute certainty. Descartes’ project of providing a firm philosophical foundation for knowledge seems doomed to fail based on this odd thought experiment.

But then Descartes realized that there was one thing even the evil demon could not fool us about: that I am thinking. The demon can fool me about the truth of what I am thinking, but not that I am thinking. Even if you are thinking something false, you have to be thinking. You could never truly say, “I thought I was thinking, but I was wrong. I just thought that I was thinking; I wasn’t really thinking.” If you thought you were thinking, then you were thinking. In other words, the evil demon can fool us about the content of the thought, but without a thought, there is nothing to fool us with. That I am thinking is an undeniable first truth.

If there is a thought, Descartes argues, then there must be a thinker. That thinker is what I will call me. I am—at least—a thing that thinks. In other words, I think, therefore I am. You cannot have an act without an actor, and thinking is an act, so there must be a thing doing the thinking, and that is me.

On this basis, Descartes then goes on to use that fact to give two proofs for the existence of God and thereby produce a foundation for science. But that’s not what is important for us. All we need is that the argument relies on us knowing (a) that we are thinking and (b) what we are thinking. In other words, for Descartes, our mind is transparent to us. We may not know whether what is in it is true, but we at least do know what is in it.

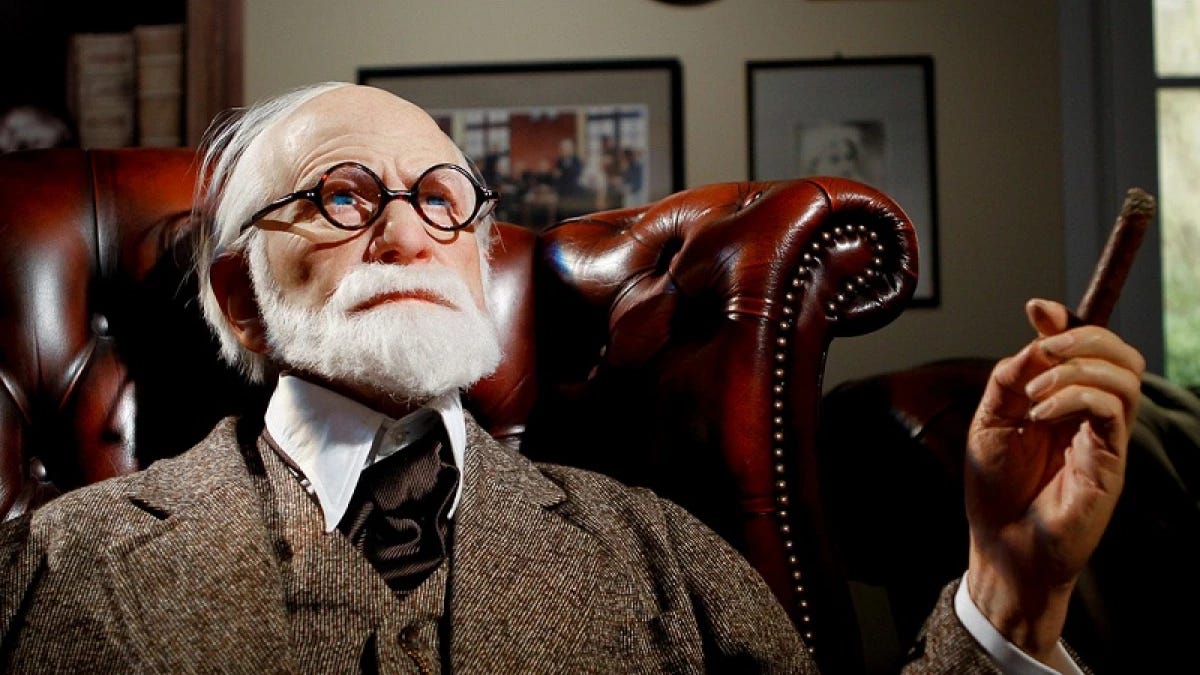

Ratman’s Weight Loss Program

Image: klkmamahvo.blogspot.com

Sigmund Freud gave us a very different picture of the mind. His model had three parts. The first is the ego. “Ego” is just the Latin word for self. It is the part of the mind that Descartes provided. When we say, “I made up my mind to have a milkshake,” that is the part of the mind Freud points to.

However, unlike Descartes, he posits two other parts of the mind that exist outside of the realm of consciousness, which the ego does not see. The id is the repository of our baser urges and desires. It operates on the pleasure principle, seeking that which brings us satisfaction. The superego is the conscience that steers us toward the right and away from the wrong. It is developed through socialization by our parents and the culture. Clearly, there will be plenty of cases where the two conflict, where the id wants something the superego will not let you have. Perhaps your id reaches for another ice cream, but your superego won’t have it, perhaps objecting, “Do you want to die of heart disease?!” If left unchecked, this conflict can cause the mind to fracture, creating neuroses, and then therapists.

Today, we often see Freud’s view criticized as unscientific, but it derives from the science of its day. At the end of the 19th century, there were two rapidly developing fields. In biology, Darwin’s The Descent of Man argued that we evolved from non-human species, and so, Freud thought, echoes of this earlier state would remain. This accounts for the animal self that is the id. At the same time, however, figures like Emile Durkheim and Max Weber were creating sociology to understand how institutions and social structures affected the way we act and organize ourselves. The sociological becomes the superego. As such, we see Freud’s picture of mind as a synthesis of the range of scientific developments of his era.

Freud thought he could unravel the actual cause of seemingly unexplained, bizarre human behaviors with it. Consider one of Freud’s patients whom he calls in his notes “Ratman.” In one episode, Ratman went on vacation with his girlfriend and his American cousin Richard. During that trip, Ratman became gripped with the sudden urge to exercise, running long distances and doing vigorous calisthenics. He did not know why.

Further discussion revealed that Ratman’s girlfriend had taken a bit of a shine to Richard, causing jealousy. This caused Ratman’s id to want to kill Richard, to eliminate the threat to his pleasure. But, of course, Ratman’s superego would not only not allow him to act on such thoughts, it would try to banish the idea altogether.

It then came out that Richard went by the typical nickname “Dick.” In German, the word “Dick” means fat. So, to save Ratman’s self-image, his superego translated the nickname and caused him to transfer his destructive impulse from his cousin to his own fat. By running in the heat and doing set after set of push-ups, he would be making himself thin, that is, getting rid of “Dick” without having the desire to harm his beloved family member.

In cases like this, Freud argues, what happens in the human mind is not known to the person whose mind it is. The psychoanalyst has the tools to disclose it, but the person themselves needs the therapist to be able to peer into the parts of their mind that they cannot see.

This is also used by Freud to explain jokes. The things we joke about most, Freud argues, are sex and violence. Why? Because these are the things the id desires that the superego disallows. That conflict creates pressure in the mind that must be released somehow. By making dirty and ethnic jokes, he contends, we are saying but not doing, and this compromise titillates the id while bypassing the bouncer that is the superego. We joke about things to relieve stress, which causes us internal tension.

Of Footballs and Other Balls

So, Freud would have a readymade explanation for the event at hand. Ben’s team’s collective id shared a desire to rid themselves of the obnoxious player on the other team. But doing so was not something their superegos would allow. Instead of acting on their anger toward his poor behavior, Ben offered a joke through a movie reference in which fictional violence could be mentioned without doing real violence. The laughter about targeting the bully was, for most of them, sufficient to alleviate the feelings.

But in the moment when the jerk was literally in the air, flying at Ben, creating more than a psychological risk, the mind already had within it a way out, and it acted to actualize the thought, recreating the idea. Freud often had his patients act out their dreams or satisfy desires expressed in their dreams. This was not a dream but a mere idea brought to life through the groin of the bully.

Is that Freudian explanation true? Shouldn’t Ben know what he was thinking and why he did what he did? What was his actual intention? Descartes would think so. So, who gives the correct answer here: Descartes or Freud?

The fascinating thing is that Ben himself, the one person we should be able to ask, isn’t sure.

It would be interesting to hear how this essay is seen in relationship to Jewish mysticism.

My understanding is that the Divine spark (as Rabbi Nachman referred to it) is our "True Self". The good Rabbi might also have "riffed" (pardon the anachronism) on Descartes by saying, "I think, therefore I am not." After all, when immersed in utter love for God, where is thought? The thinking dissolves and the radiance of one's essence of Being is so bright there is no room for any doubt regarding Existence.

About Freud, he simply used the German words, "I, "Above I" and "It" - it was his translator, James Strachey, who wanted Freud to be appreciated as a scientist, and what better way to do that than introduce Latin terms, which have led to interminable arguments about what the "ego" is; whereas everyone knows immediately the undoubtable sense of I.

The Romantics of the 19th century wrote enormous amounts about the Unconscious, but very much like the earlier Jewish mystics, it was the Divine mixed with the Demonic which made up this so-called Unconscious, and it was the task not just of the mystic but ultimately, every human being to distinguish the two, to the point that one was led by the Divine and one opened to God to transform the so called 'demonic" (after all, demon est deus inversus)

It seems a shame Steven could not have conveyed this to his son Ben. There was no doubt a power of the divinity of Life in that slide which innocently sought victory. And seen in a brighter Light, the anger or desire for revenge could have been recognized simply as that same Divine Energy inverted by the imposter "little I" which is the main source of all human problems. (Think Musk and Trump the last few days!)

Great contrast between these two renowned men and a fantastic story! That poor kid, ouch.

It's interesting that the language of “Cogito ergo sum” limits the underlying truth. Thought indicates a thinker, but thoughts and even the thinker is something that only exists in awareness. I am aware of thinking, and I am aware that I think I am the thinker, which is just another thought.

Indeed ANY observed phenomenon implies an awareness. We are aware of sensations, emotions, colors, shapes, textures, and all forms in this world. And because we are aware of these things, there must be something that is aware. That is the I AM.

From a religious wisdom tradition perspective, God in the Biblical Old Testament said, "I AM THAT I AM." Jesus in the NT said "I AM [which is] the way, the truth, the life" (brackets are my interpretation). Tradition says he was talking about himself, but what if he was pointing to the divine part of us? What if the I AM is the gateway to the divine?