Dance To the Music

Sly Stone’s ghosting of philosophy

Image: Sly Stone, paramountplus.com

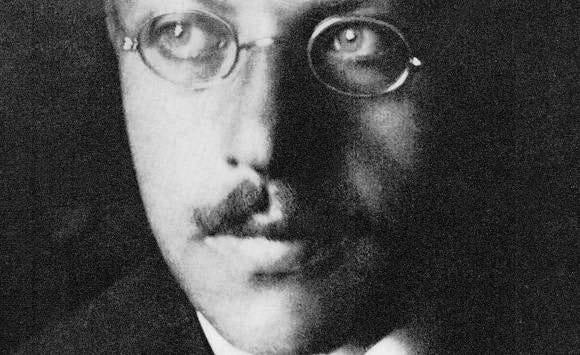

Philosopher Franz Rosenzweig wrote, “Love brings to life whatever is dead around us.” Sadly, Sly Stone, DJ extraordinaire and the charismatic and energetic frontman of Sly and the Family Stone, just died on Monday. Stone brought love to life with his music. From “Everyday People” to “I Wanna Take You Higher,” Stone brought people together in the name of understanding and joy.

Many of his lyrics are straightforward. We are all the same. Love one another. But different is the refrain of his hit “Thank You for Letting Me Be Myself Again.” The psychedelic 60’s were infamous for embracing paradox, but this line is only confusing if we take the understanding of the self as we find it in Enlightenment Western philosophy. If we apply Rosenzweig’s thought, Stone’s sentiment becomes both clear and profound.

You Are You

The starting place of Enlightenment philosophy is in the head. John Locke wondered what makes us the same person we are today as we were ten years ago. The obvious answer seems to be that there are some properties that form our essence, the core of our being.

The problem, of course, is that we are always changing. No matter what property you pick, it could be different later. Yet, surely we can reasonably say, “I used to have that property, now I have this one.” In other words, I am the same thing now as I was then, even though the qualities I embody are radically different.

So, he moved from the body into the mind. But again, we learn. We change our beliefs. How can properties of the mind define our being?

He realized that there is one important difference among everyone who was around ten years ago. I only remember what happened to me. That must be it. I am a consciousness over time. I am the contents of my mind, which only I have access to. In philosophical talk, I am a subject who has experiences, and that subjectivity is me.

This then leads to all the usual puzzles of how do I know that when you see red, you are having the same experience as when I am seeing red? In fact, how do I know you even have a mind and are not just a robot? Or further, how do I know that anything exists outside of my thoughts? Does the external world exist, or is it just me?

If we start this way, I am me. I have no choice. I could not be anything other than me. Why would someone else let me be myself? This seems to be something trivial. Why would I thank someone for something that must be true? Stone’s lyric seems absurd.

But if we have a different understanding, one that comes from the dialogic tradition of Jewish thought, the line becomes deeply meaningful.

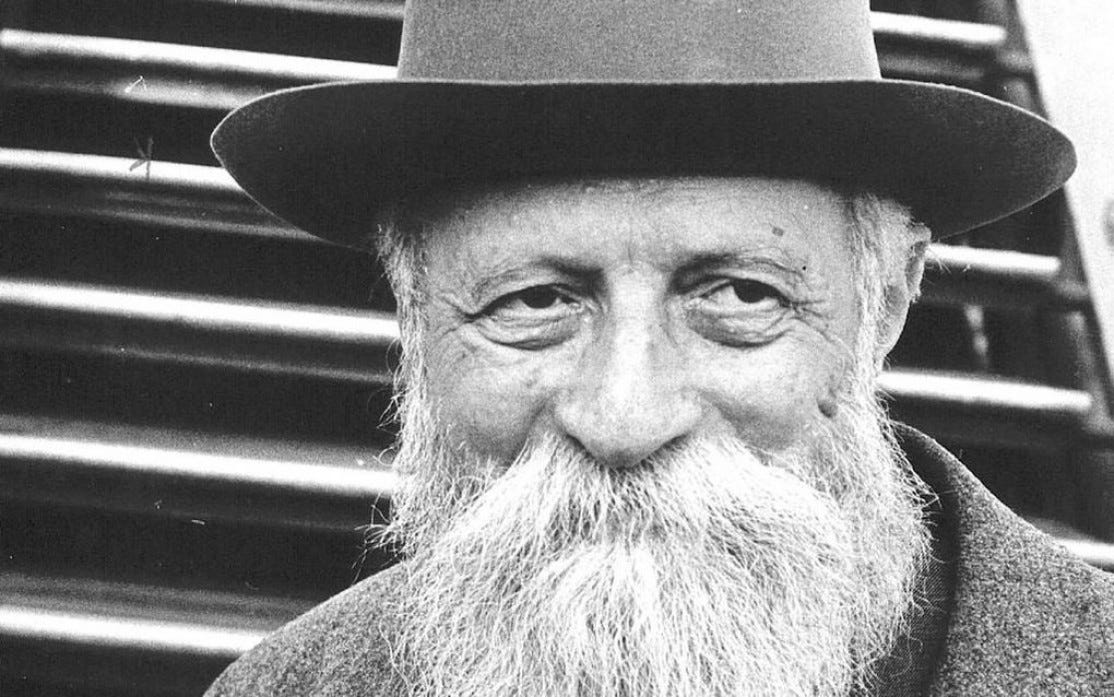

Rosenzweig and Buber Explain Sly’s Existential View of the World

Image: Martin Buber, wearepublic.nl

Franz Rosenzweig walked out of the trenches of the First World War with betrayal in his heart for Western Philosophy. Philosophy showed no concern for his fear of death while in trench warfare. The war destroyed his philosophical sense of ego, like dynamite blowing up self-importance. His emerging abstract fame now meant nothing.

Rosenzweig left his professorship, devoting himself to the concerns of everyday people. He started a free school for assimilated Jews in Frankfurt, the Lehrhaus, seeking to re-engage people with the deeper questions of life. It enrolled ten thousand students at one time. The greatest living Jewish German philosophers lectured there, from Walter Benjamin to Martin Buber and Eric Fromm. They wanted in, demanding to dance to the music being played. There was no “que sera, sera” at this party. The Lehrhaus instructed that everybody is a star, the other is light, not the type for which Plato leaves the cave, but light from love, love absents darkness.

Using dialogue as a model, Rosenzweig betrayed the “selficating,” self-absorbed subject he found in philosophy like that epitomized by Locke. We cannot get stuck inside our own heads, inside our own selves. To the contrary, as in conversation, Rosenzweig explains, we live in virtue of one another. It’s as if he is saying, I get high on you. Before one may love oneself, one must first be beloved. To be chosen, to be beloved, is to fly higher and higher, much higher than jumping alone. Dancing! As John Dunne said, “No man is an island.”

Martin Buber loved Rosenzweig, but when reading their letters, one gets the impression that the older Buber is the student. Their dialogues awakened them into response, and it was in reply that each was able to see and reflect on his philosophical errors. It is in response that one finds oneself, where the possibility for self-reflection is born. It requires the other to let you be yourself.

In communication with Rosenzweig, Buber also betrays Western philosophy. He focuses on the necessity of dialogue, noting that before one can have a monologue, one has first been part of a dialogue. Buber assumes that the other or “the world may be incomprehensible,” but they are “embraceable.” Every day. “Feelings dwell in [one]: but [one] dwells in [one’s] love,” which involves more than oneself. Love between two creates the possibility not only for hot fun in the summertime, but for existence through interconnection.

Image, Franz Rosenzweig, alchetron.com

Dialogic philosophers are careful to note that we can never be one with something apart from ourselves. Buber shows that two people in love do not make one, nor does a person transfixed on a bush while meditating become one with the bush. One may be at once with the bush but not one with it, just as two people in love may be both at once for one another but never one. If they’re one, they can’t be for one another and give love to one another.

Twenty-five years later and sixteen years after Rosenzweig’s death from ALS, French/Lithuanian philosopher Emmanuel Levinas walked out of a Nazi slave labor camp; humans had abandoned him every day for five years. He notes he was only a wordless monkey in the eyes of those who saw him, eyes that stripped him of humanity. Rosenzweig’s betrayal of philosophy was a glass of cold water in hell for Levinas. Just as Rosenzweig seemed betrayed by philosophy in the killing trenches of World War I, Levinas got betrayed by the world. Philosophy was of no help to a Nazi slave.

Levinas is angry but doesn’t leave philosophy like Rosenzweig, instead he sought to expose its moral failings. Going further than Buber and Rosenzweig, he asks philosophy, are you ready? There’s only one way out of this mess. Look around. See them, philosophers? Those are everyday people. You are now responding for the other, the other who awakens you to more than yourself. Philosophy no longer needs to ask “how am I aware of you, the other?” It’s hard for them. Seconds ago, philosophers thought the other can’t strain your brain. Those everyday people bring the possibility of bringing you close, triggering you into being for more than you. Perhaps you will find yourself singing a simple song for the other. In that singing, you come to be who you are by virtue of your doing to them, for them, with them.

Suppose I see you walking on the street and call your name. The second you hear me, the second you realize somebody’s watching you, your awareness is now in response to me. How you reply is your creation for me, but that you reply to me isn’t a choice for you. Ignoring me is still for me. Runnin’ away responds to me. Indifference toward the other is just as much for the other as one’s love for the other.

I will not have intentions toward you unless directed to respond to you. Return is often pregnant with possibilities for fun and love to come your way. Love transcends philosophical concepts and reasoning, always betraying, perhaps even ghosting, philosophy. No one opened philosophy books at Sly’s performances. Love enveloped everyday people at Sly’s shows. There was no room for hate, indeed, not even for Luv n’ Haight together.

Perhaps Levinas had just seen Sly and the Family Stone when he said: “Love is not a passive emotion but a fundamental ethical responsibility towards the Other.” In other words, thank you for letting us be ourselves again, playing for change:

Diff’rent strokes for diff’rent folks, and so on, and so on, and scooby doobie, doobie.

To me there was nothing confusing about the statement. Too often, society demands conformity rather than allowing individuality. When one allows someone to be him- or herself that is an act of humane-ity. It's not a paradox; it's just true.