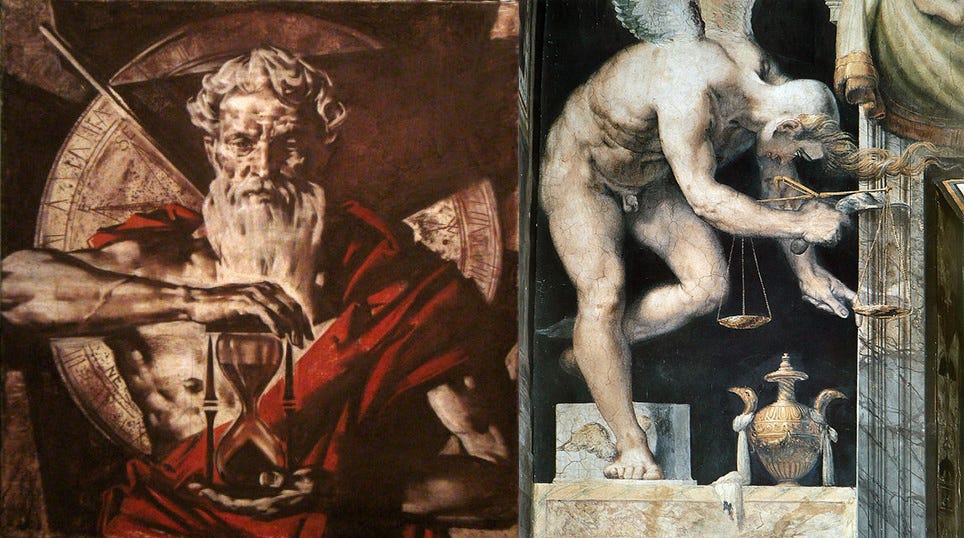

CrossFit, Chronos, and Kairos

A Midlife Quest for Time

Image: freepik.com

A core dimension of the human condition is to live in time. And a core part of living in time is that, as we age, we find that our relationship to time changes.

I’m sure you recognise this from personal experience. For me, at least, time moved at an almost languid pace as a child, with months feeling like years and years like an age. As is well known, adults often look back nostalgically on their school summer holidays—which in the UK only last about six weeks—and remember them as feeling impossibly long.

The explanation for this is presumably that a year is a substantial proportion of a child’s life, so it subjectively feels longer as a result. By contrast, as someone rapidly approaching their late thirties, I’m finding that time is taking on a different pace—an uncomfortably fast one.

This change, which nearly all of us will face or have faced, brings with it certain existential challenges. Is there anything we can do about it? And how do we live well, when time feels like it’s slipping away from us ever faster?

Reflecting on midlife

When I began to think about things that I could do to cope with the passage of time, I realised that I’m already doing some. However, these are not deliberate and thoughtful responses to aging. Instead, they’re unconscious and faintly amusing coping strategies.

Most notably, since hitting the back half of my thirties, I’ve suddenly developed a keen interest in fitness and outdoor pursuits.

Is this an early midlife crisis? The anxiety of bidding farewell to the first flush of youth? Whatever the label, it’s a transition that many men seem to undergo at this point in life. In their late twenties, they might have been happy to spend a weekend drinking beer and watching football on TV, but a decade on, they’re into protein shakes and posting on the Reddit CrossFit page.

Why does this happen?

Image: thedreamcatch.com

There are probably multiple answers, including, of course, a feeling that one’s physical peak is receding into the distance, and that it’s a good idea to at least try to keep it in view. But another is the aforementioned pace at which time begins to move.

Chronos and kairos

Having adult responsibilities—any combination of working, parenthood, running a household, and helping elderly relatives—is a good and natural development, one that we should embrace on our path to maturity.

The only problem is that with such responsibilities comes routine, and with routine, time slips by with unnerving speed. The cycle of getting up, going to work, cleaning the house, etc., can dominate one’s days, and we soon find that the days bleed into weeks, and weeks into months. Hence, the temptation to get into some kind of physical activity—both to try to claw back the fitness which naturally and gradually passes away in this period of life, and also to break one’s routine and slow the ever-hastening passage of time.

One way to philosophically understand what’s happening here is by distinguishing between objective and subjective time. The former is time measured mathematically, through seconds, minutes, hours, and so on. The latter is how we actually experience time, which, as discussed, can ebb and flow.

However, we can go further and draw on the Greek distinction between chronos and kairos, two words for two different senses of time. This terminology appears not only in the works of philosophers like Plato and Aristotle but also in the New Testament.

Both chronos and kairos can be broadly understood as branches of subjective time. The former, chronos, is time experienced as duration, as a forward flow. Because of its chronological character—past through to future—this branch of subjective time lends itself to measurement and makes the notion of objective time possible. Kairos, by contrast, is about a pivotal moment that can’t be captured quantitatively. It’s about the right moment, the intervention that arrests and qualitatively changes the meaning of chronological time.

When trying to disrupt the routine of adult life with something novel, we use kairos to change the flow of chronological time. This breaks the forward movement of time experienced as a result of our daily routine, and as a result, our sense of time’s pace stretches out once more.

Grasping – and letting go

This all seems reasonable enough. Clearly, however, if we end up incorporating repetitive exercise into our routine, such that it becomes part of the latter, then, whatever the fitness benefits may be, time will eventually speed up again.

For this reason, one might think it best to incorporate a wide variety of new experiences in new places to try to stretch time out yet further. The more we fill our time with new things—so this line of thinking goes—the more our sense of time swells to accommodate them.

The approach to life just described makes some sense, and is completely understandable from an emotional point of view. None of us, after all, want to feel that we’re not making the most of the time we have. The issue with it, however, is that it represents a kind of grasping at time, a needy craving for more and more. As I say, this is perfectly understandable, but it could end up diminishing the quality of our time; thus, we wouldn’t be making the most of it.

If that’s not immediately persuasive, maybe think about it this way. If I perpetually try to maximise my sense of time by filling it up with plenty of new experiences, am I actually likely to enjoy that time in a spontaneous and fulfilling fashion? Or is it more likely that the forced and calculated way in which I approach those activities means that I won’t really be absorbed in them?

Perhaps then, a combination of striving and letting go is the best way to both extend our lived time and actually enjoy the time we have. If we can make a degree of peace with the hastening speed at which time moves, whilst also trying to fit in a degree of novel activity to slow it down somewhat, we may have the healthiest way of approaching the coming of middle age.

And even if that doesn’t fully work out, there are always the fitness benefits, at least.