Nothing in this world can take the place of persistence. Talent will not: nothing is more common than unsuccessful men with talent. Genius will not; unrewarded genius is almost a proverb. Education will not: the world is full of educated derelicts. Persistence and determination alone are omnipotent.

—Calvin Coolidge

The former president’s musings on persistence are inspiring, but I humbly beg to differ. In the same way that talent, genius, and education cannot account for success, it seems fairly evident that even where persistence is omnipresent, it is still far from omnipotent.

Here’s a musical example:

Back in 1968, the great Johnny Cash agreed to perform two (now famous) shows at Folsom State Prison in California. Normally, he was rather particular about the songs in his set lists. But on the eve of the concert, he met with his friend, Reverend Floyd Gressett, who ministered for state prisoners. Gressett gave Cash a tape of “Greystone Chapel,” a song written and recorded by Folsom prisoner Glen Sherley. After listening to the song, Cash agreed to perform the song the next day. How cool is that?

The lyrics, along with Sherley’s life story, inspired hope. Arrested for armed robbery, he was serving a sentence of five years to life. His song described the Folsom chapel as a refuge for him and other prisoners, and even in some of the toughest of circumstances, they felt that they could see God’s grace:

Inside the walls of prison, my body may be, but the Lord has set my soul free.

Johnny was so captivated by Sherley’s story and songwriting skills that he later made requests to public officials to grant him parole. Cash even arranged for a small record company to make a recording of Sherley’s own prison concert in 1971, which made it easier for officials to believe Cash when he said he would give him a job if paroled.

After Sherley’s release, Cash stayed true to his promise and invited him on tour. But, tragically, Sherley was erratic during the tour, even threatening a key member of Cash’s band. When Cash learned of it, he promptly fired Sherley, who returned to California and fell back into drug abuse. On May 11, 1978, Sherley committed suicide. The news really took a toll on Cash.

He had taken a chance on Sherley when many people wouldn’t have. He felt that grace and forgiveness were God’s commands and didn’t take them lightly. He was able to look at his own life, recognizing that he had his own issues and was a recipient of grace and mercy from God. So taking a chance on Sherley was not just an act of kindness but a powerful reflection of his faith.

And yet, despite the noble efforts, despite Cash’s persistence, it all crashed and burned. Why is that? Because the reality is that despite our intense desires, hopes, dreams, and mighty strivings, there are forces at work that thwart our persistence time and again. No one, no matter how accomplished, powerful, brilliant, or well-intended they may be, can alter these forces (which some might argue are all the products of a singular, ultimate force).

“Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!” declared haughty Ozymandias from the decaying ruins of a forgotten empire, and if neither he nor Coolidge nor Cash could fulfill their deepest will, what chance do we have?

The answer is none at all. That is unless we learn to adjust our will.

Surrender yourself entirely, and accept His will in whatever happens.

—Rumi

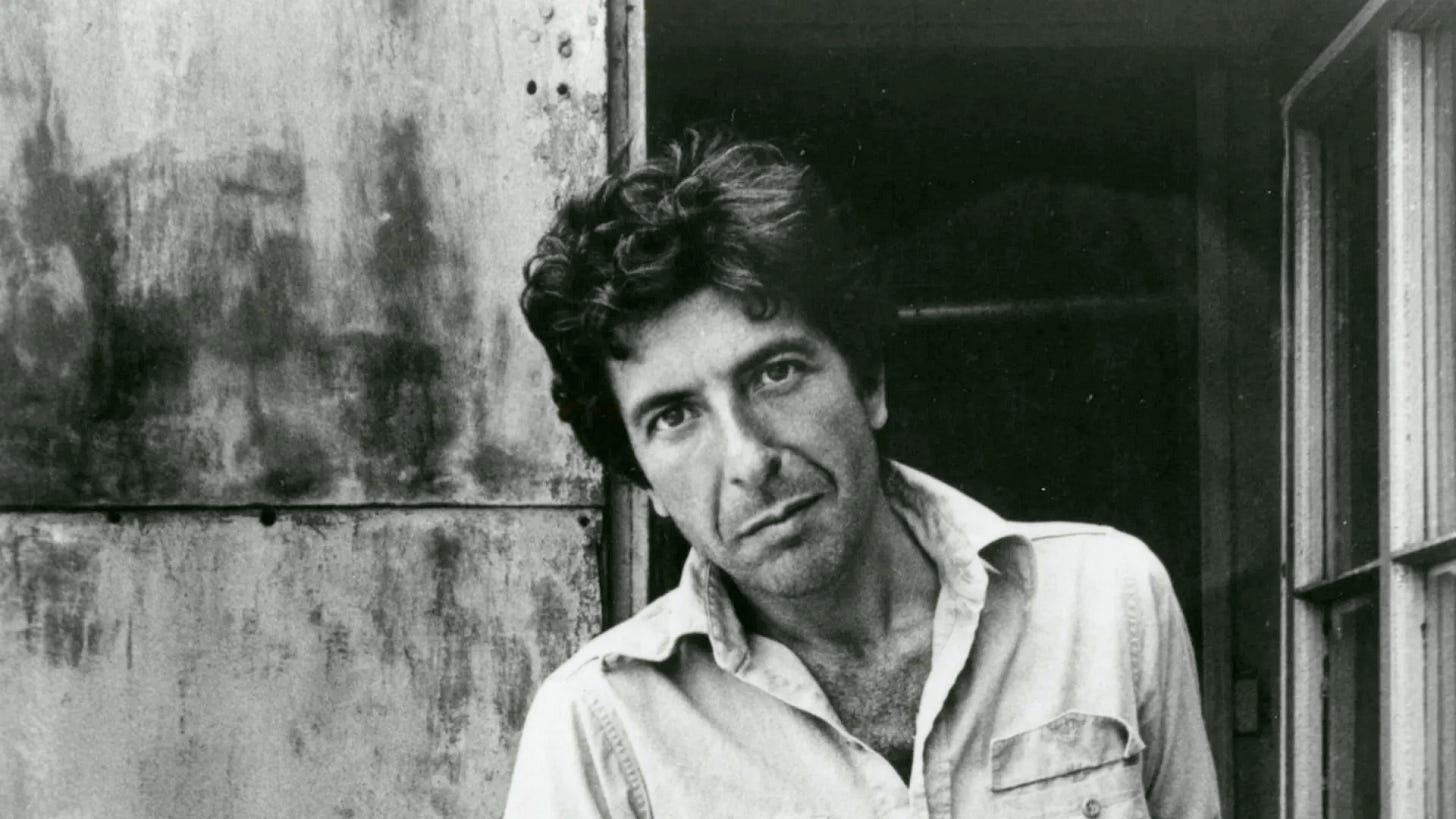

Leonard Cohen was one of our most spiritual and deeply-reflective artists. Always honest and ever-searching, his lyrics were bold in what they were willing to tackle and stylistically original. He explored this idea of reidentification of the will in 1984’s brilliant “If It Be Your Will.” The best version of this tune that I know came from the Leonard Cohen documentary “I’m Your Man” and was performed by Antony Hegarty.

This is a stellar performance of a simple yet profound song. Hegarty’s soft and vulnerable voice is a unique twist on the gruff baritone of Cohen’s original. The gentile waltz-time lilt is mesmerizing, and when the backup singers kick in at the end it just becomes otherworldly.

Cohen was a master lyricist, and one of the recurring leitmotifs of his wordsmithing is the notion of brokenness:

There’s a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in.

It’s a cold and it’s a broken Hallelujah.

In this instance, he sings (ostensibly to God) “from this broken hill.” To his everlasting credit, Cohen never seems angry or bitter about the broken state of existence but seems to regard it as a melancholy yet potent opportunity. In his way of thinking, the lowly is a container for the light, and the splintered nature of our difficult reality is nothing less than rivulets of goodness winding their way inside.

What could be more important to a singer than his ability to sing? Yet, he is willing to sublimate this intense and fundamental desire for the sake of a will that is higher and greater than his own:

If it be your will

That I speak no more

And my voice be still

As it was before

I will speak no more

I shall abide until

I am spoken for

If it be your will

If it’s true that there is an ultimate unity and purpose to reality then our highest calling can only be to align ourselves with it. Sometimes this will feel right and good, but other times it will be frightful and confusing. Most of us don’t do well with having our will thwarted—feeling (as we do) that we know what’s best for us, for those around us, and for the world. Nonetheless, if there is a greater power that governs reality, it stands to reason that it has an infinitely greater capacity to understand what is ultimately good and will bring that about, with or without our consent—not punitively, but as an act of love.

Paradoxically, by giving up what we want and choosing to want what the Ultimate Will wants, we can end up gaining a deep-seated peace of mind by finally getting everything that we want. None of this is to suggest that we should abandon striving for what we feel that we need and desire, only that we should develop a spiritually healthy response when the answer is “no.”

Make His will like your will, so that He will make your will like His will.

—Mishna

Elizabeth Kubler Ross taught us that acceptance is the natural conclusion of our greatest emotional battles and that there is no shortcut to arrive there outside of processing through various stages that ultimately correspond to how we relate to what has happened. There’s an emotional and spiritual impoverishment that accompanies the non-fulfillment of our will (when it really matters). And yet, in the midst of the degradation, when our will bore no fruit, and our persistence proved futile, there lies the greatest possibility of growth and awareness.

Let your mercy spill

On all these burning hearts in hell

If it be your will

To make us well

And to draw us near

And bind us tight

All your children here

In their rags of light