Before Narnia and Middle-earth {Arts}

George MacDonald, the Forgotten Writer Who Inspired Tolkien and Lewis — and Saw Science as Divine Light in Creation

The imaginative spirit and moral compass of our modern age owe much to the creative genius of a man most readers have never heard of: George MacDonald. A Scottish author, poet, and visionary thinker, MacDonald was the pioneer of modern fantasy. He lit the way for J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Lewis Carroll, and L. Frank Baum, and influenced critics and reformers such as G.K. Chesterton, John Ruskin, Mark Twain, Dorothy Sayers, W.H. Auden, Octavia Hill, and Josephine Butler.

MacDonald’s work is remarkable not only for its imaginative brilliance but for the breadth of his vision. He saw the natural world as alive with meaning and beauty, science as a language of deeper truths, and imagination as the key to understanding both. He believed that science and spirituality worked in harmony, not opposition, and described creation itself as “a transparency through which the light of God can be seen.” For readers today—whether religious or not—his writings offer a striking vision of how fantasy, science, and compassion belong together in the human search for meaning.

The Father of Modern Fantasy & Inspirer of the Inklings

The modern fantasy novel begins with MacDonald’s Phantastes: A Faerie Romance for Men and Women, published in 1858. Its young hero, Anodos—whose name means “pathless” in Greek—enters a parallel world through a portal that appears in his bedroom on his twenty-first birthday. This world, hidden yet ever-present, overflows with supernatural forests, elves, knights, a wise White Lady, enchanted castles, and magical libraries. But it is also shadowed by danger: Anodos confronts the darkness of his own soul, an ogress tempting him with forbidden knowledge, and a wolf-like monster lurking behind a false idol.

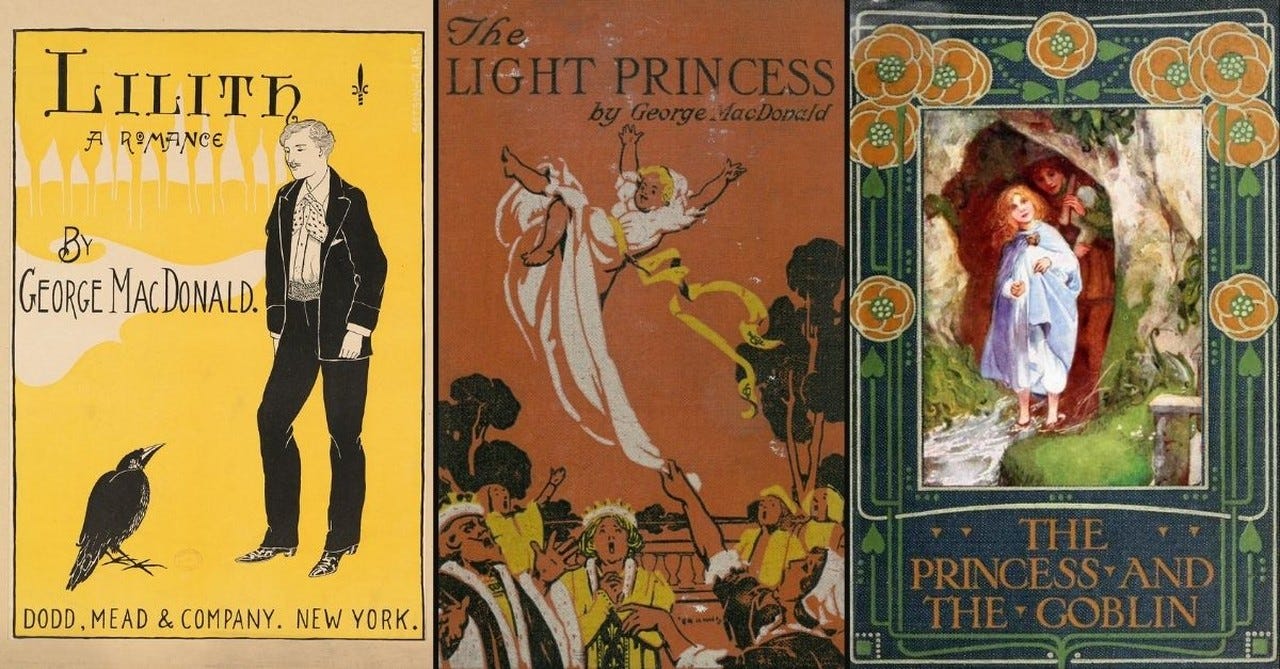

In this dreamlike story, MacDonald created the blueprint for modern fantasy: the otherworldly realm, the quest for truth and beauty, the struggle against inner and outer darkness. Later writers drew deeply from this well. Tolkien acknowledged that his youthful reading of MacDonald shaped his imagination. The goblins of The Hobbit echo the stone-like goblins of MacDonald’s The Princess and the Goblin and The Princess and Curdie. Tolkien’s Ents and the malicious Old Man Willow resemble MacDonald’s enchanted forests. Galadriel, the luminous Lady of Light in The Lord of the Rings, has clear antecedents in the White Lady of Phantastes and the grandmother figure of The Princess and the Goblin.

C.S. Lewis also openly named MacDonald as his “master.” When Lewis, then an atheist, picked up Phantastes at a railway bookstall in 1916, he later recalled that “my imagination was, in a certain sense, baptized.” Though his conversion to Christianity came much later, Lewis claimed that nearly everything he wrote bore MacDonald’s imprint. In 1962, when asked to list the books that most shaped his philosophy of life, Phantastes still held the number one place.

MacDonald also shaped the literary destiny of Lewis Carroll. Carroll, uncertain about the value of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, nearly abandoned it. But MacDonald encouraged him to test the story on his children, who adored it. Their enthusiasm persuaded Carroll to publish, and the rest is history.

Without George MacDonald, modern fantasy as we know it—Narnia, Middle-earth, Wonderland—might never have taken root.

Imagination as the Power of Creation

Image: crosswalk.com

MacDonald saw imagination as humanity’s greatest gift and deepest responsibility. It was not mere fancy or escapism, but a participation in the creativity woven into the fabric of life itself. To imagine well was to join in the act of creation.

For him, imagination was nourished by truth, beauty, and goodness, and when properly cultivated it reached into the very heart of reality. “Law,” he wrote, “is the soil in which alone beauty will grow; beauty is the only stuff in which Truth can be clothed. Obeying law, the maker works like his Creator.” For MacDonald, even fantasy worlds must follow their own internal order, just as nature follows its own laws. Imagination, when guided by beauty and harmony, became a way of seeing more deeply into existence.

He argued that it is often not the things we perceive most clearly that shape us, but the undefined yet vivid visions of something beyond. In this sense, imagination is not opposed to reason but complements it, expanding the horizons of what reason alone can grasp.

Science as a Transparency of Light

Because imagination and science both depend on law and order, MacDonald saw them as partners, not rivals. Science described the workings of the universe, while imagination illuminated its meaning. In his words: “Every fact in nature is a revelation… creation is a transparency through which light can be seen.”

For him, scientific laws were not cold mechanics but signs of life and purpose, “the waving of God’s garments, waving so because he is thinking and loving and walking inside them.” While science revealed the how, imagination and wonder pointed to the why.

MacDonald often illustrated this conviction with a flower. A man of science, he said, might pull it apart, describe its structure, and explain its functions. But the truth of the flower lay in its living beauty—the radiant presence that compelled a smile or stirred a tear. To stop at analysis was to miss the point. The flower’s beauty was the clue, the invitation to deeper meaning.

For MacDonald, then, beauty was not ornamental but fundamental. It was a force at the root of reality, as essential to understanding as reason itself.

Suffering, Freedom, and Evolution

MacDonald embraced the scientific reality of evolution, but in a way radically different from many of his contemporaries. Where others saw competition and the “survival of the fittest,” he saw freedom, individuality, and moral growth. Evolution, to him, was the stage on which life’s deepest drama—the growth of conscience and choice—could unfold.

He imagined creation as a long and difficult separation from its source, so that individuality and freedom could emerge. The end of this process was not separation, but reconciliation: the free and conscious choice of harmony. “The final end is oneness,” he wrote, “an impossibility without freedom.”

Suffering, in this view, was not meaningless. It was part of the creative process that allowed life to deepen in love and freedom. In his fiction, heroes endure trials not simply as tests, but as ways of being drawn more fully into the heart of meaning.

This vision set him against the misuses of Darwinian theory in his time. He rejected Social Darwinism and eugenics outright. To apply the logic of survival of the fittest to human society, he argued, was to betray the very essence of humanity.

Social Conscience and the Power of Beauty

MacDonald’s conviction that life’s purpose was moral and relational shaped his fiction. Again and again, he chose as his heroes those whom society deemed unfit: the hunchback Stephen, the simpleton Rob of the Angels, the deaf and mute Hector of the Stags, the epileptic Elsie Scott, the fool in St. Michael and St. George. In a culture increasingly fascinated by eugenics, MacDonald made the weak and vulnerable the carriers of truth and beauty. They were, in his words, “pain-bearers,” whose endurance contributed to humanity’s redemption.

Beyond his novels, MacDonald worked directly for social reform. He collaborated with Octavia Hill and her sister Miranda in their efforts to bring beauty, nature, and art into the lives of the urban poor. In a letter, Hill recalled MacDonald telling her: “When we have seen the perfectly beautiful, if we have the right kind of eyes, it helps us to see all that is lovely in less beautiful things.” This belief—that beauty awakens perception, and perception awakens compassion—was central to his life’s work.

Through lectures, performances, and writings, MacDonald championed the idea that beauty was not a luxury but a necessity for human flourishing. To live surrounded by ugliness was to be starved of something essential. To encounter beauty, even in the smallest forms, was to be restored to hope.

Why MacDonald Matters Today

George MacDonald’s name may be little known today, but his legacy runs deep. He was the pioneer of modern fantasy, the mentor of Lewis Carroll, and the guide of Tolkien and Lewis. His vision of imagination as a creative power, science as a transparency of light, and beauty as a healing force offers a strikingly fresh perspective for our own age.

At a time when science and spirituality are often cast as enemies, MacDonald’s vision insists they belong together. At a time when society still struggles with exclusion, his compassion for the marginalized reminds us of the moral force of imagination. And at a time when many question whether beauty has any role in public life, his conviction that beauty heals the world feels more urgent than ever.

To rediscover George MacDonald is to rediscover the roots of fantasy, but also to glimpse a vision of life where imagination, science, and compassion converge in the light of meaning.

A beautiful summation of the philosophy of a highly creative and benevolent thinker.

OMG, I simply MUST get hold of some MacDonald's books. I have many of the same beliefs that you describe here--"While science revealed the how, imagination and wonder pointed to the why." I love the choice of heroes as disabled individuals. YES! I love evolution as also a spiritual awakening. YES. I didn't think anybody thought like this.